O consumer, where art thou?

Most of the analyses of the Central Bank of Turkey’s rate hike last week concentrated on its impact on banks and corporations. There was surprisingly little mention of consumers.

Most of the analyses of the Central Bank of Turkey’s rate hike last week concentrated on its impact on banks and corporations. There was surprisingly little mention of consumers.

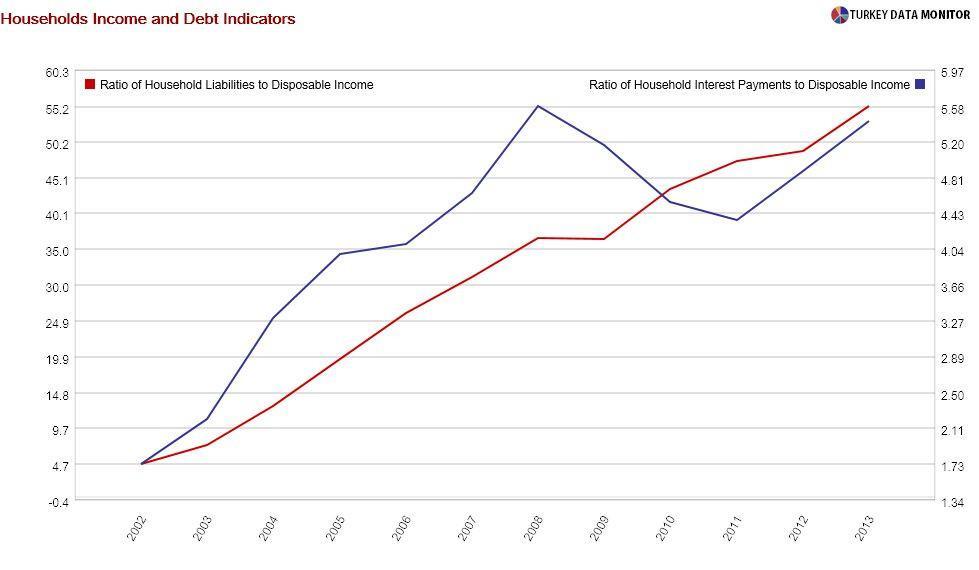

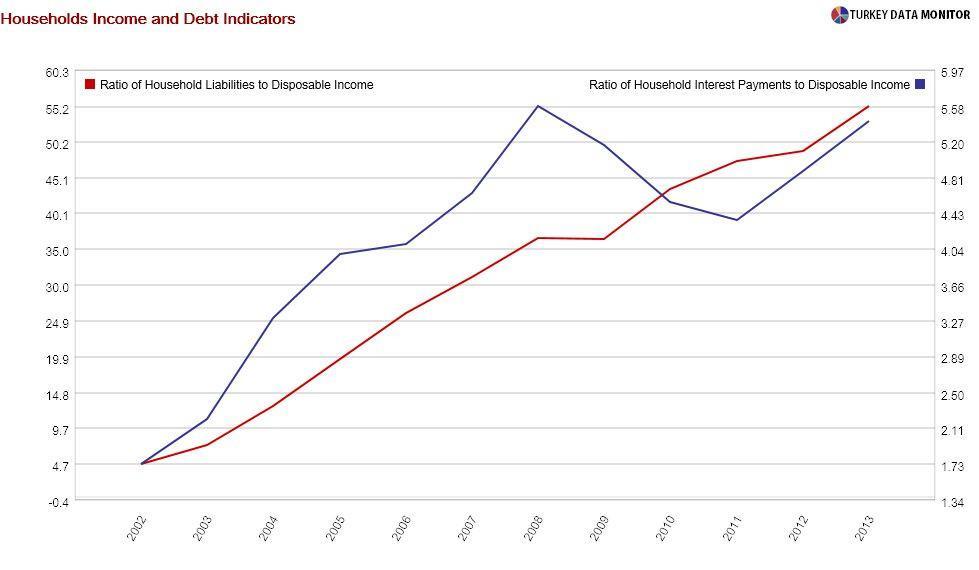

It is true that, as government officials like to point out, Turkish households are still less leveraged than their counterparts in many other countries, but their indebtedness rose considerably after the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power. The ratio of household liabilities to disposable income increased from 4.7 percent in 2002 to 55.2 percent in 2013.

Interestingly, the rise in leverage has been driven by the environment of macroeconomic stability after the 2001 crisis. The sharp fall in interest rates has played a role as well, especially since 2008. As a result, many middle-class Turks could buy houses and cars for the first time. No wonder home and auto sales soared.

But there was a catch. This rising debt burden would be sustainable only if household incomes continued to rise rapidly. Kemal Derviş, the former Turkish minister who engineered the post-crisis recovery program, summed up neatly in a recent column at the Huffington Post:

“For a household that has experienced 6 percent annual income growth for several years and has increased its debt to disposal income ratio from 10 percent to 40 or 50 percent, a slowdown of income growth to, say, 2 percent a year, could lead to serious hardship by increasing the debt service to income ratio in a way that would force consumption cut-backs, despite still growing income.”

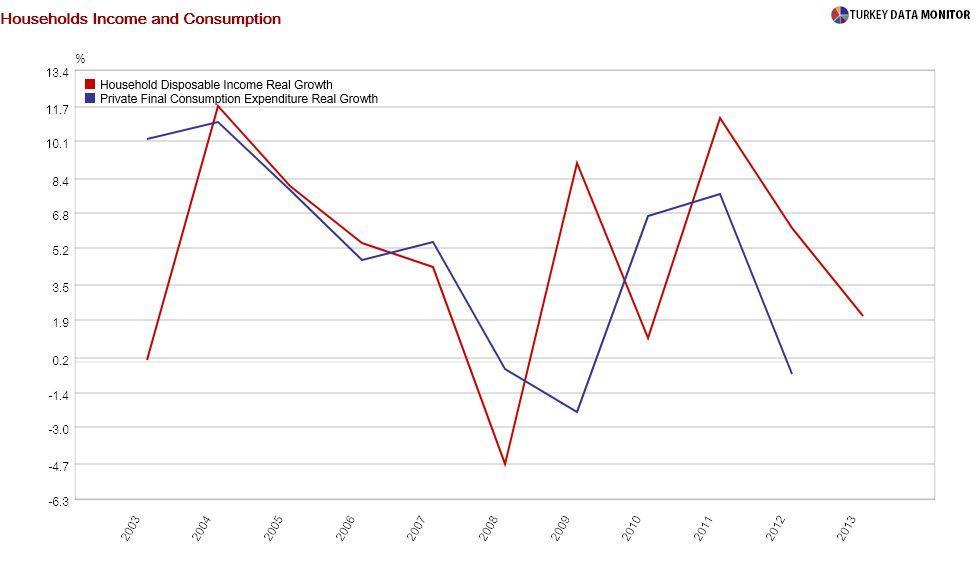

There does indeed seem to be a relationship between households’ income and consumption in Turkey.

More importantly, households never experienced consecutive years with dismal income growth during the last decade. A year of negative or near-zero income growth was usually followed by one with double or near-double digit growth. But with household income growth at 2.1 percent in 2013, and not likely to exceed that this year, there is a good chance that Derviş’s nightmare scenario will be materialized.

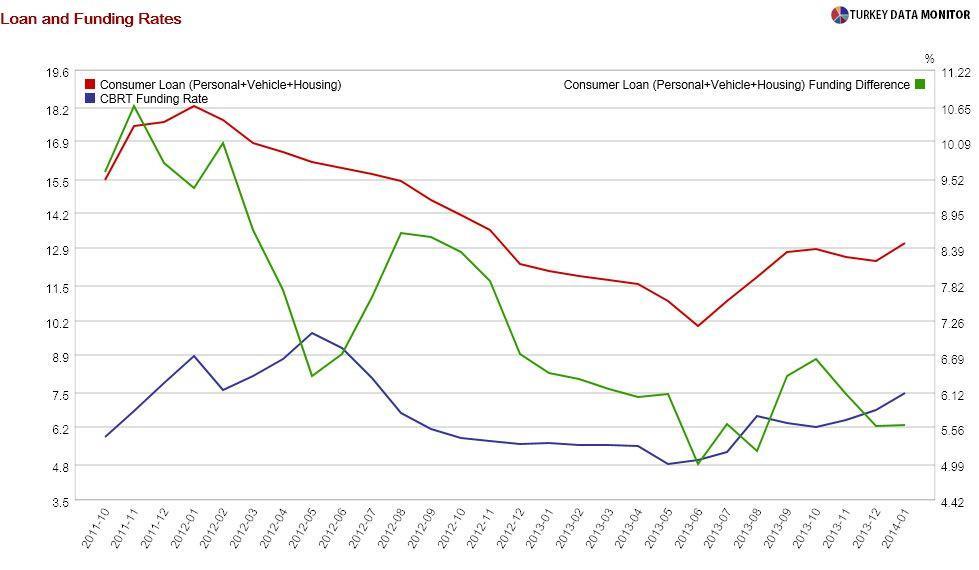

It gets worse. Derviş ended his comments with a warning, “If real interest rates rise, the problem is aggravated.” In fact, years with low or negative income growth during the past decade were accompanied or followed by a decline in interest rates, as the Central Bank responded to the slowdown. Not this time!

Moreover, I feel banking analysts could be underestimating the impact of the hike on lending rates. Most expect a 1.5-2 percentage point increase, consistent with the rise in the policy rate from 7.75 to 10 percent. However, as I explained in the previous column, the effective rate hike is more like 2.5-3 percentage points. Besides, most assume the 6 percentage point difference between lending and the Central Bank’s average funding rates will be retained. That spread has usually been higher.

It seems like we will be indeed be looking for the Turkish consumer this year- as well as the sectors that depend on her.