No woman, no growth

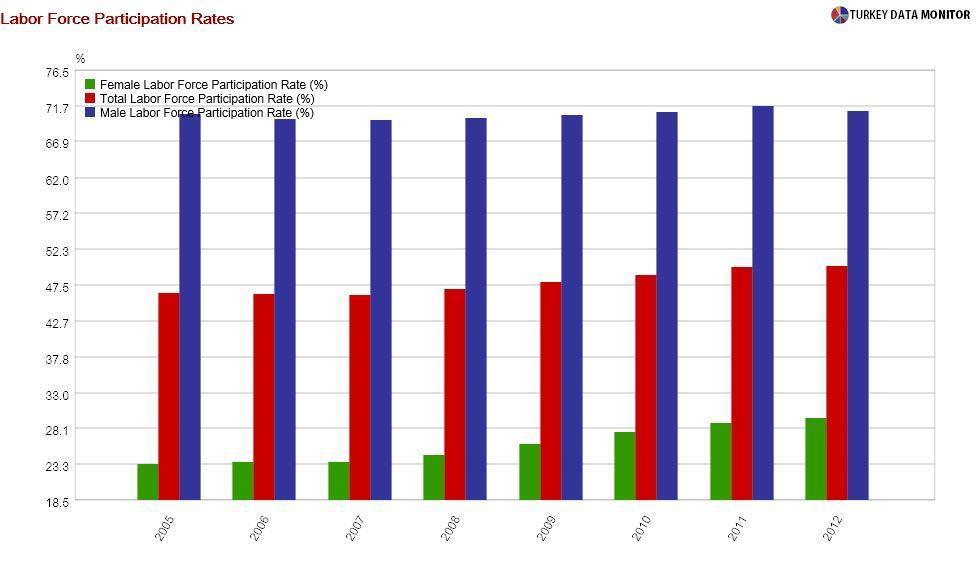

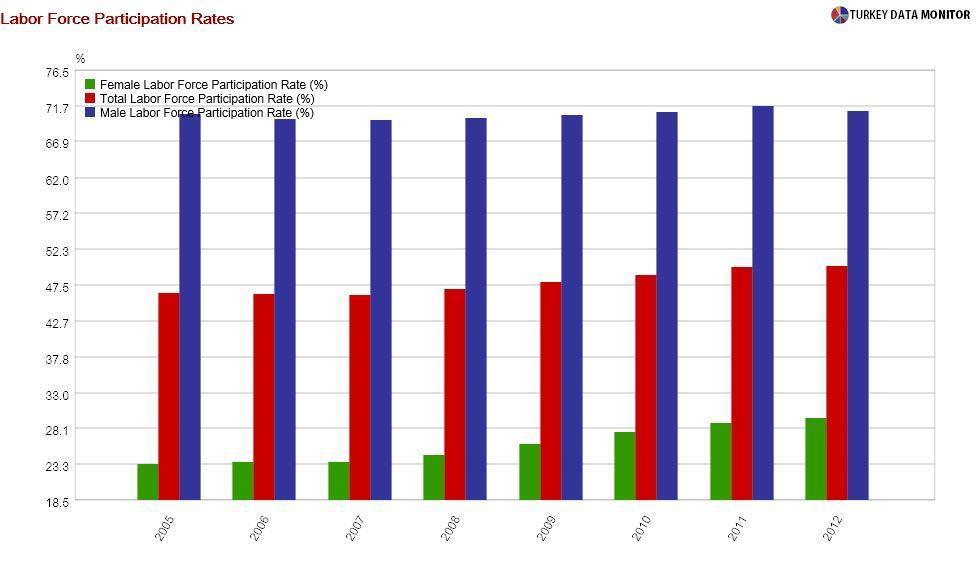

Did you know that Turkey does not utilize half of its working age population? According to the annual labor statistics released on Mar. 6, the labor force participation rate (LFP), which is the ratio of those working or looking for work to the population over the age of 15, turned out to be 50 percent in 2012.

Did you know that Turkey does not utilize half of its working age population? According to the annual labor statistics released on Mar. 6, the labor force participation rate (LFP), which is the ratio of those working or looking for work to the population over the age of 15, turned out to be 50 percent in 2012.Turkish LFP is so low because only 29.5 percent of women are in the labor force. Every year, I make it a point to write about Turkish women’s labor market woes on or around International Women’s Day. I always bring up the issue of low women’s LFP, and, every year, without exception, I get an angry comment from a reader, saying that women “choose” to stay at home to raise their children.

Although a recent World Bank survey found out that many women do not work because of disapproval from husbands or society, others indeed choose to stay at home. It is basic economics, really. What options do women have when childcare is not available or too expensive? Daycare is simply not economical for uneducated women, who would have to work long hours in the informal economy with low wages. No wonder Turkish women’s LFP goes up with education.

The government is aware of the issue, and they have been working on widening/subsidizing childcare for a while. But women’s rights activist Hülya Gülbahar claims that they are quite happy keeping women at home. In her interview with Barçın Yinanç in the Daily News on March 4, she argues that policies such as financial support to take care of the elderly at home and tax exemption for women working from home show that incentives are “provided in a way to keep women at home.”

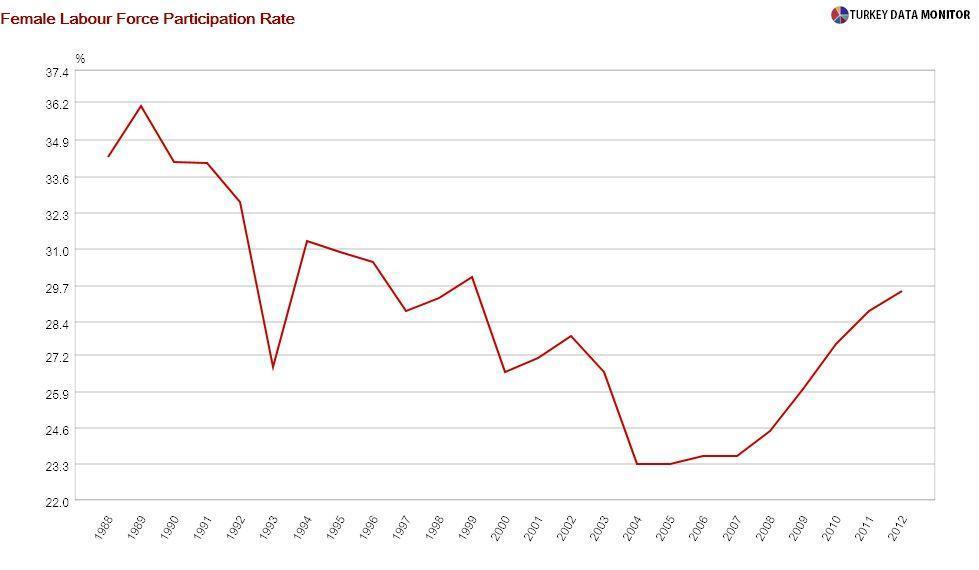

I am not a big fan of conspiracy theories, and the government has an official goal of increasing women’s LFP to 38 percent by 2023. Women’s LPF did indeed hit an all-time low of 23.3 percent in 2004, two years after the ruling Justice and Development Party came to power, and then hovered there until 2008. It has been consistently on the rise since then.

Some of these women probably started working when their husbands lost their jobs in 2009, when the Turkish economy contracted 4.8 percent, and then never turned back. But Gökçe Uysal from the Istanbul think-tank BETAM shows that most of the increase in LFP has been in cities and among low-educated women. She concludes that reductions in social security premium contributions for women, enacted in 2008 to encourage female employment, must have worked.

But just why is increasing women’s LFP important? Ankara think-tank TEPAV’s Güneş Aşık offers some clues. Using simple and logical assumptions, she calculates that increasing women’s LPF to the government’s target would add 0.4 percentage points to Turkey’s potential growth rate. Achieving the OECD average of 61 percent would add another 1 percentage point.

Unfortunately, it seems Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is more interested in having every healthy Turkish woman give birth to three children than getting them into work.