Monetary policy exacerbates inequality

As I explained

in my last column, one major difference between academic and market economists regarding monetary policy is the latter are expected to say what the Central Bank will do, rather than what it should do. On that measure, most did well yesterday: As they predicted, the Central Bank

lowered its policy rate by 0.5 percentage points.

Another major difference between the two is their time horizon. Market economists are mainly interested in the short-term consequences of monetary policy, especially on financial assets. Even when they consider the economic impact of monetary policy, they are much more concerned about the medium than the long-run. In this sense, they would be interested in

a recent Central Bank paper which argues that lower interest rates causes higher inflation.

They would also be somewhat interested in the fact that the Central Bank’s ignorance of inflation is

hurting the competitiveness of Turkish firms. After all, if they are at a disadvantage against rivals in other emerging markets because of the consistent inflation differential between Turkey and its peers, their – and the economy’s – prospects would be affected.

Market economists would nonetheless disregard the fact that lower rates are enforcing inequality in three distinct ways: First, as I argued in

my Feb. 7 column, a report by the Istanbul think tank, Bahçeşehir University Center for Economic and Social Research (Betam),

showed inflation hit the poorest most during the last decade: Prices for the richest and poorest 20 percent of the population rose by 131 and 144 percent respectively. Inflation for the poorest was actually slightly lower from 2003 to 2006, but the trend has reversed since then.

A recent report by Turkish Industry and Business Association (TÜSİAD)

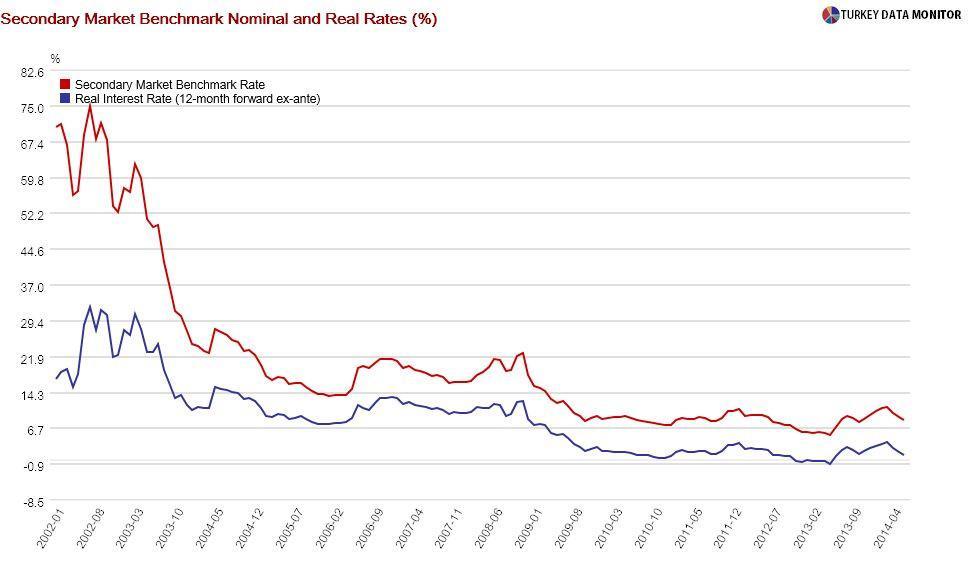

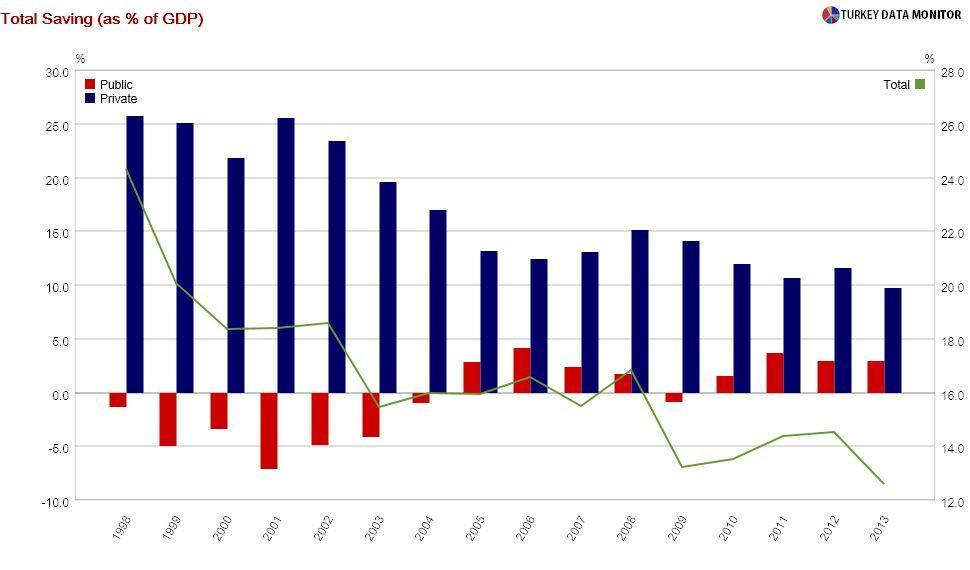

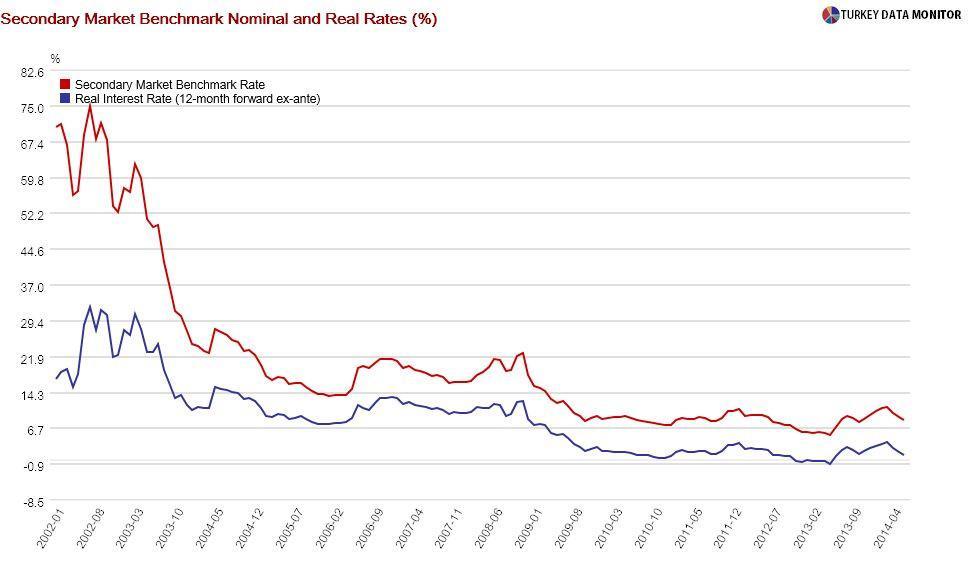

looks at a more direct effect of interest rates on inequality. The authors argue the sharp fall in interest rates in the early years of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) actually lowered inequality by reducing the interest rate income of rich households.

However, further declines in rates after 2007 caused the savings of lower-income households to fall.

A 2009 paper by economists Murat Üçer and Caroline Van Rijckeghem, as well as a

2012 World Bank report actually showed lower rates did indeed cause private savings to plunge. The TÜSİAD report goes a step further by investigating the impact on different income groups.

Finally, born-again former market economist George Cooper

convincingly shows in his most recent book

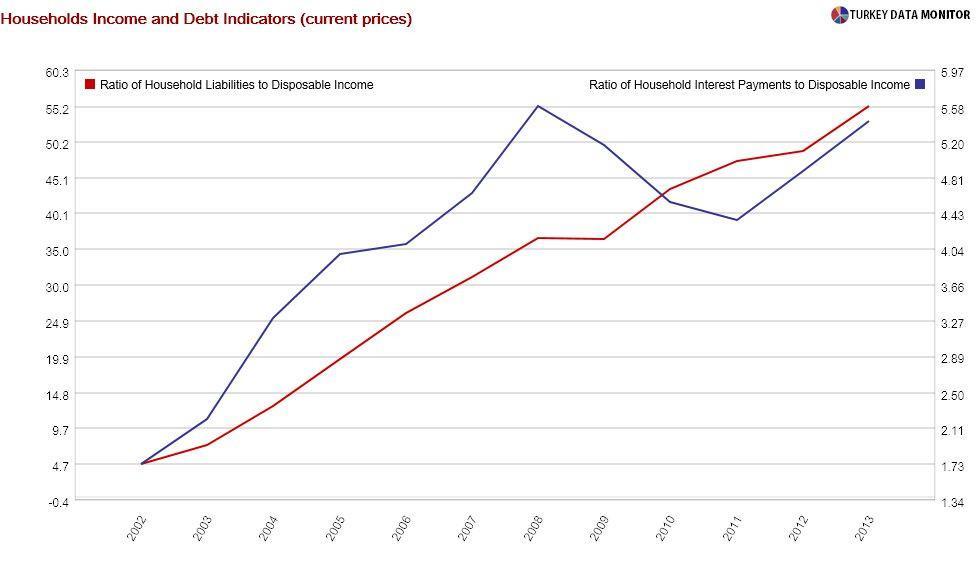

“Money, Blood and Revolution” that low interest rates increase inequality by burdening the poor with debt. Household liabilities indeed rose sharply during the past decade in Turkey, but I have not seen a study that has looked into the rise in debt among different income groups.

But maybe, I should forget about the impact of the rate cuts on inequality and enjoy the financial gains bestowed upon us by the low rates. After all, in the long run we are all dead – even though John Maynard Keynes

did not encourage debt, as some claim.

As I explained in my last column, one major difference between academic and market economists regarding monetary policy is the latter are expected to say what the Central Bank will do, rather than what it should do. On that measure, most did well yesterday: As they predicted, the Central Bank lowered its policy rate by 0.5 percentage points.

As I explained in my last column, one major difference between academic and market economists regarding monetary policy is the latter are expected to say what the Central Bank will do, rather than what it should do. On that measure, most did well yesterday: As they predicted, the Central Bank lowered its policy rate by 0.5 percentage points.