Markets ignore geopolitics, but for how long?

As their name implies, market economists are supposed to follow markets closely. Since I am not one anymore, I am no longer glued to the Reuters terminal. Nor do I feel the urge to check the Bloomberg app on my Blackberry every couple of minutes – even though I have been dumped because I supposedly love my smartphone more than anything or anyone else. Go figure! :)

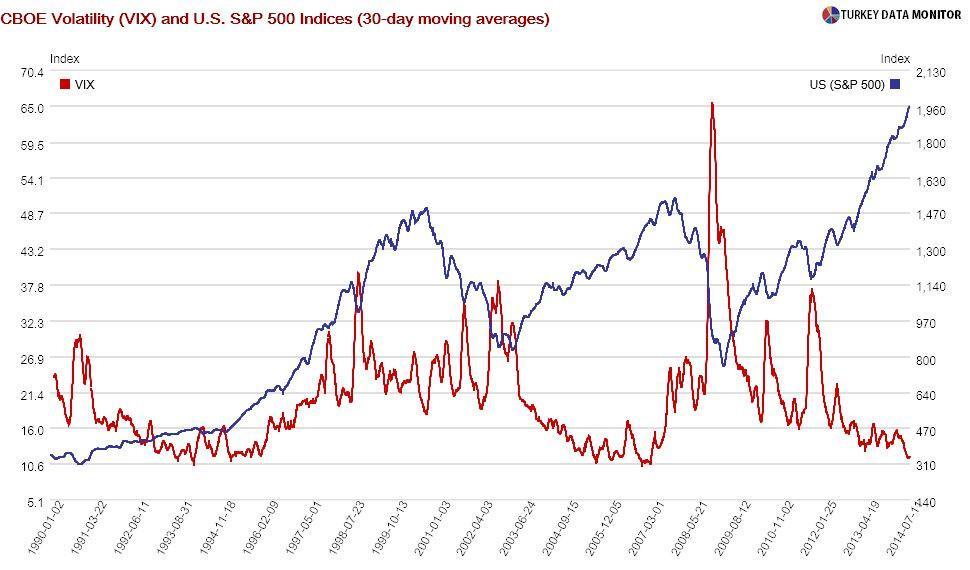

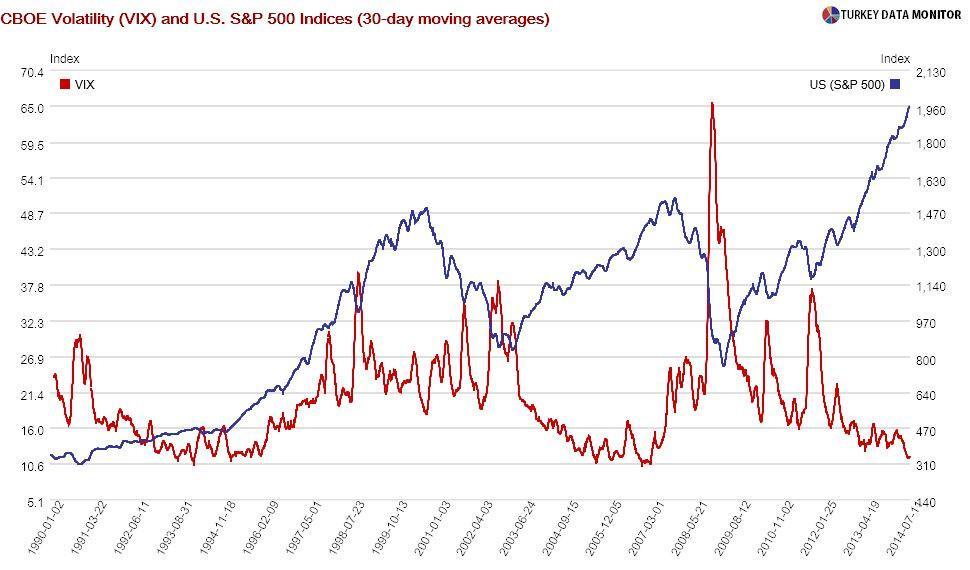

As their name implies, market economists are supposed to follow markets closely. Since I am not one anymore, I am no longer glued to the Reuters terminal. Nor do I feel the urge to check the Bloomberg app on my Blackberry every couple of minutes – even though I have been dumped because I supposedly love my smartphone more than anything or anyone else. Go figure! :)Anyway, I still try to stay up-to-date on financial developments and I always read Financial Times’ daily market recap after American markets close. The heading for Tuesday’s piece was “Equities shrug off geopolitical tensions.” The article the next day noted that “a further fading of geopolitical concerns helped pave the way for U.S. stocks to reach fresh record highs.” The Vix index, a measure of the implied volatility of U.S. stock options often touted as the markets’ fear gauge, is at levels before the global crisis. It has been this low only once before, in the early 90s.

Investors’ ignorance of geopolitical risks is actually not a recent phenomenon. On the contrary, it has been one of the defining market themes of the last couple of years: The Thai coup and the turmoil in Egypt and Syria did not disrupt the markets at all. More recently, the fighting in Iraq, Gaza and Ukraine has been overlooked as well.

It is somewhat understandable that the former events were ignored. After all, they were local conflicts that could not have impacted the global economy. But markets, like the mob, used to be fickle. In the past, investors would be worried about “contagion” in the event of a coup in a country they probably could not show on the map, even though economists or experts on politics could not find a single reason for it.

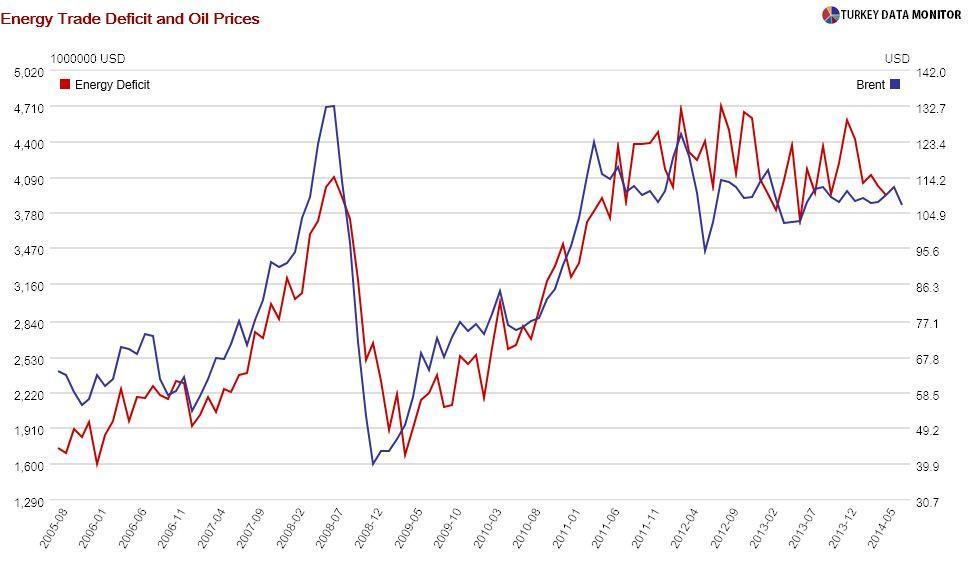

To the extent that much ado about nothing is avoided, this is a positive development. But markets’ reactions to the more recent conflicts are more like “no ado about a big thing.” Contrary to the earlier ones, these have the potential to raise energy prices, as the International Monetary Fund noted in the update to its economic forecasts yesterday, on July 24.

Turkey would be one of the countries affected most in such a scenario. For one thing, as every Turkey economist knows, every dollar rise in oil prices increases Turkey’s energy deficit by roughly $300-400 million. A surge in the price of oil would also raise Turkey’s inflation – the country’s other Achilles’ heel, even though the Central Bank thinks denial is a river in Egypt.

Luckily, investors could continue to disregard geopolitics for a while because they are not really ignorant. On the contrary, geopolitical risk comes out as their main worry in investor surveys. Why don’t they put their money where their mouth is? The answer, my friend, is the cheap money central banks are blowing.

After all, as Citi’s then-CEO Chuck Prince famously noted a few months before the global crisis, you have to keep dancing while the music is playing. Just don’t forget that everyone will scramble for seats when it stops – and Turkey will probably be left without one.