Macroeconomics 101 for finance ministers

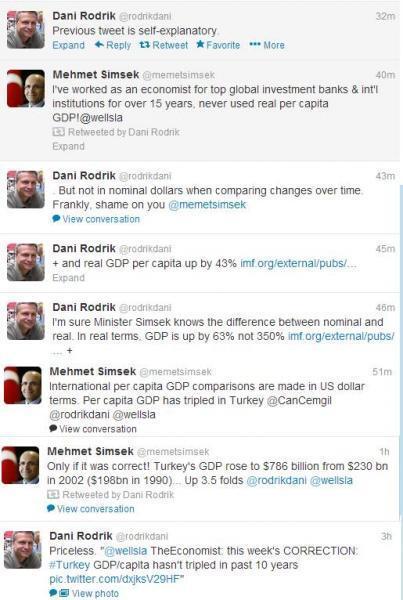

One of the most interesting Turkish economic developments of the last few days was a heated exchange on Twitter between Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek and Princeton University’s Dani Rodrik on measuring Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

One of the most interesting Turkish economic developments of the last few days was a heated exchange on Twitter between Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek and Princeton University’s Dani Rodrik on measuring Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

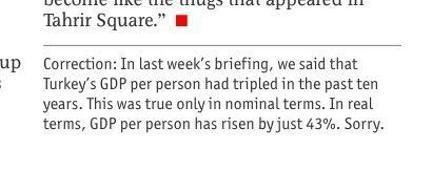

It started when Rodrik tweeted a correction from The Economist: “In last week’s briefing, we said that Turkey’s GDP per person had tripled in the past ten years. This was true only in nominal terms. In real terms, GDP per person has risen by just 43 percent. Sorry.” Şimşek countered, arguing that the correct way to measure GDP was in nominal dollars.

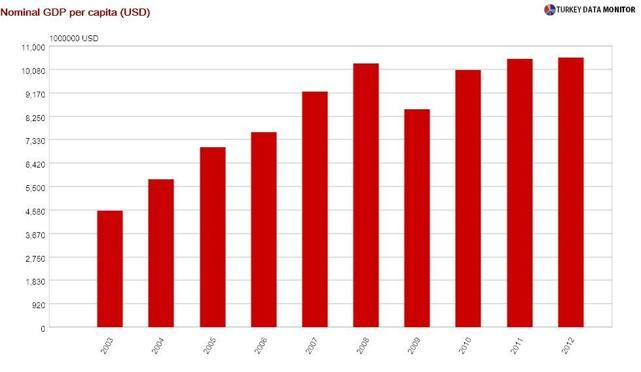

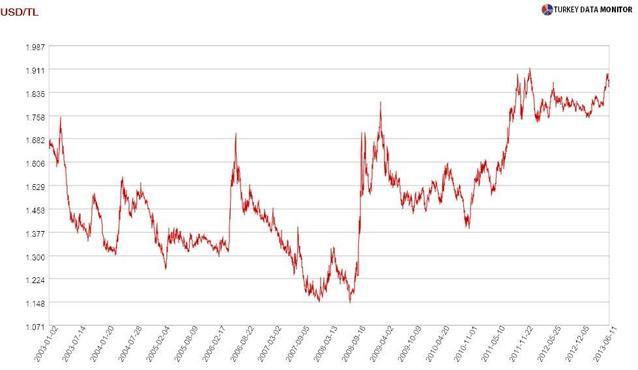

Turkish GDP per capita did indeed increase from $3,516 in 2002 to $10,537 in 2012. However, looking at GDP per person in dollar terms results in two serious complications: First, you are subject to fluctuations in the dollar lira exchange rate.

That rate was 1.65 at the beginning of 2003 and 1.78 at the end of 2012. That’s only an 8 percent depreciation over a ten-year period, but the lira fell below 1.15 against the dollar in January 2008. It then had two sharp depreciation episodes, one later that year and another in 2011. It has been hovering around 1.80 since 2012, thanks to the Central Bank’s goal of reducing volatility in the exchange rate.

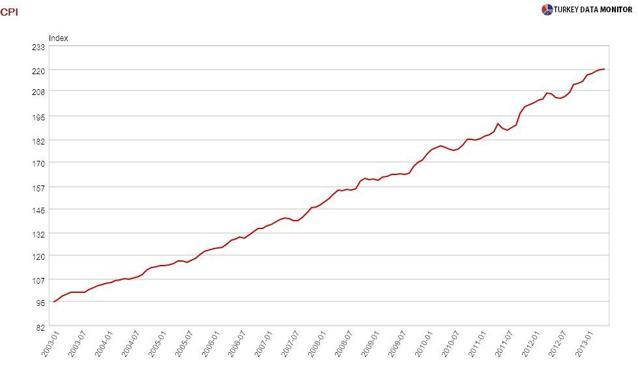

That’s not the end of the story. Any nominal GDP measure would not be taking care of inflation. Even if Turkey had not grown at all during the last decade and the exchange rate had been fixed, GDP per capita in dollars would have more than doubled. Prices rose 125 percent from the beginning of 2003 to the end of 2012.

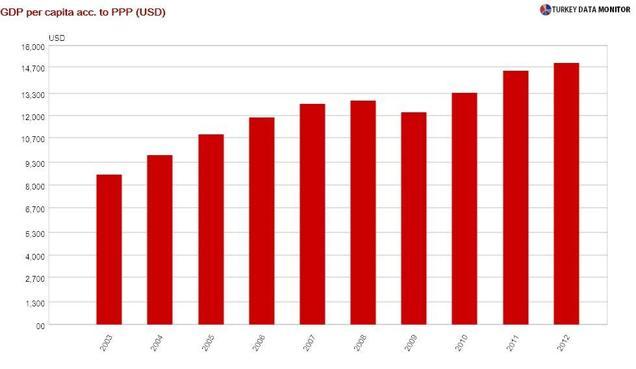

Isn’t there a way out? You could adjust for purchasing power parity (PPP), which takes into account the prices of comparable goods in different countries. An EU report the Minister mentioned on June 19 to support his arguments actually uses this approach. The rise in Turkish dollar GDP per capita now looks much more modest. But I don’t use this methodology unless I am comparing living standards across countries in any given year, as it is fraught with several issues.

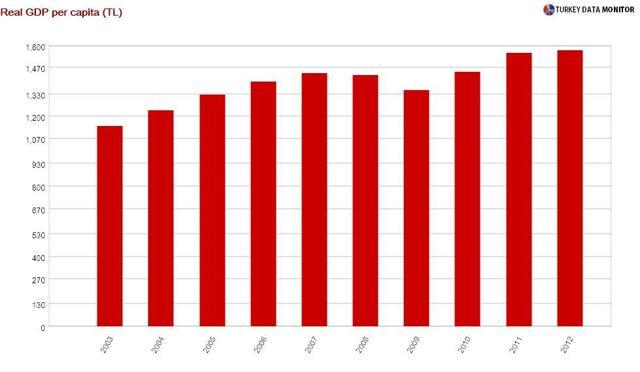

The most accurate way to look at the performance of an economy through time would be real GDP in domestic currency. This methodology calculates GDP with prices from a given year. Domestic inflation is therefore accounted for, and since we are dealing with local currency, we don’t have to worry about the whims of currency markets, either. Growth figures across the world are actually calculated from real GDPs.

To make comparisons easier, I normalized GDP per capita from the three methodologies to 100 in 2003. The rise in nominal GDP per capita in dollars until the end of 2012 turned out to be 132 percent. PPP-adjusted dollar GDP per person increased by a much more modest 75 percent during the same period, and real GDP per capita rose 38 percent.

It is normal for non-economists, even journalists from the venerable Economist, not to be familiar with the intricacies of GDP measurement. But I just can’t believe I had to explain all this to a Finance Minister.