Lord of the incentives

The

title, cheesy even by my standards, is not actually mine. It was on the front

page of a pro-government daily after the

new investment incentive scheme (NIS) was announced by Prime Minister

Erdoğan, followed by a more detailed presentation by Economy Minister Çağlayan, on April 5-6.

I was initially somewhat disappointed: I was hoping that somewhere among the long list of incentives would be some kind of support for my beloved Beşiktaş to renovate their historic stadium. Our family business in Marmaris could do with some free cash to help out with our planned investment next year as well.

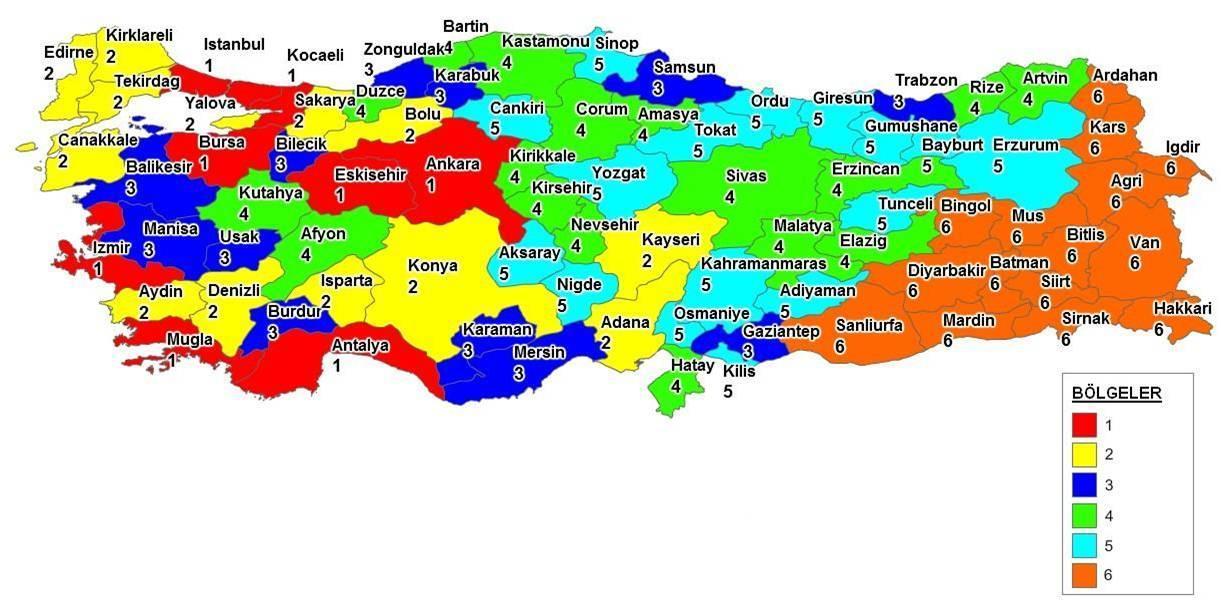

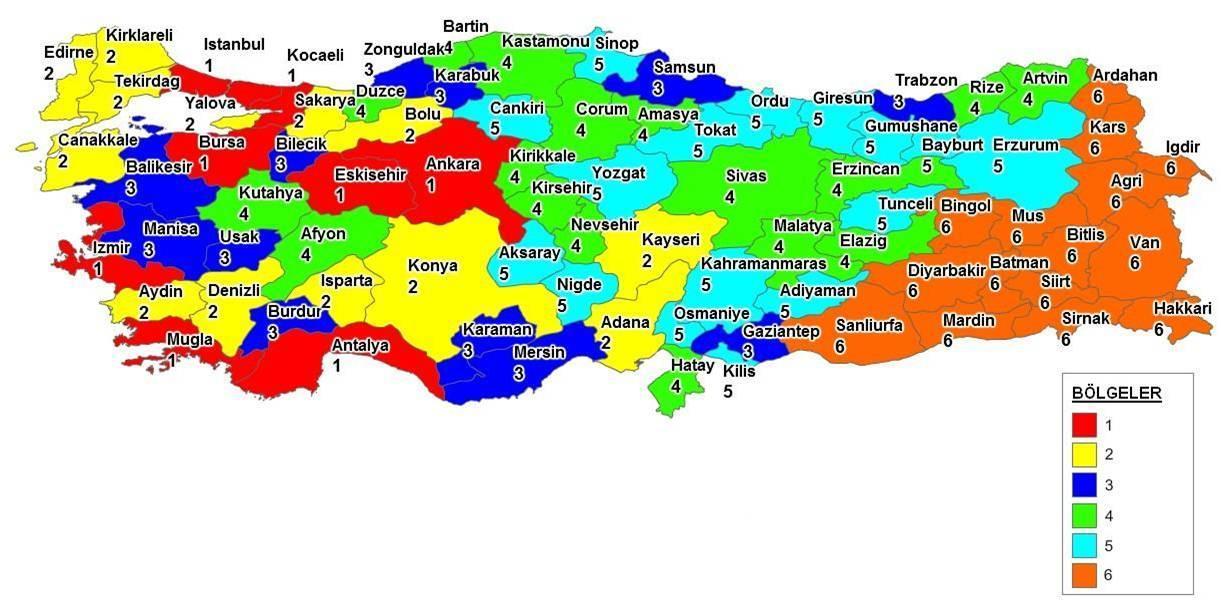

But İstanbul and Muğla are both part of the first "region" of provinces, which reflects their relatively high level of development. This first region, of six in total, isn't getting much support, but then I saw that tourism investments in designated tourism areas would be treated as part of the fifth region. It is great to be getting money for an investment I would have already made! That’s probably why the private sector has reacted so positively to the NIS.

Setting

aside the question of the incremental effect of the policy, I am skeptical that

the government, or anyone for that matter, can cherry-pick “winners”, although

some of the designated strategic sectors such as large-scale pharmaceuticals, schools

(a recent note by Ankara think-tank TEPAV argues that the budgetary cost of the

new education reform will be rather large) and maritime/railway transportation

make a lot of sense.

This is actually the fourth investment incentive scheme by the ruling Justice and Development Party in their decade-long rule. And to render unto Erdoğan what is Erdoğan’s, they actually keep getting better each time. The first two schemes in 2004 and 2006, for example, had the same support for 49 provinces, which unsurprisingly resulted in the more developed of the bunch getting the lion’s share of investment.

Despite such important improvements, I have serious doubts that the new NIS could magically satisfy the multiple objectives of reducing the current account deficit, raising the value added in production, increasing development in less-developed areas and reducing regional disparities.

For example, while the NIS is supposed to decrease imports by encouraging domestic production of intermediate inputs, it is also designed to increase the overall level of investment. As Turkey is suffering from a chronic savings shortfall, without an increase in the savings rate, we could as well end up with a higher current account deficit. Harvard’s Dani Rodrik, who has written extensively on incentives, has apparently made a similar point.

The NIS is also aiming to increase Turkey’s global competitiveness by supporting clusters and R&D. Since Turkey was ranked 59 in World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, this sounds like a step in the right direction. But improving the business climate, as I argued last week, would be a much better method for achieving that goal.

But

the government has been strangely

reluctant to implement structural reforms. Without those, the NIS looks

like a temporary patch. Or it is merely

compensation for the sour investment climate.