Getting the Turkish story right

Delivering a keynote address during lunch at the Central Bank of Turkey conference “Global Finance in Transition” on May 7, Deputy Prime Minister and economy czar Ali Babacan emphasized the structural reforms of the last few years.

Delivering a keynote address during lunch at the Central Bank of Turkey conference “Global Finance in Transition” on May 7, Deputy Prime Minister and economy czar Ali Babacan emphasized the structural reforms of the last few years.Turkey did manage economic stability thanks to an expansionary fiscal consolidation, inflation targeting and banking sector clean-up after the 2001 crisis, but microeconomic and structural reforms did not follow macroeconomic ones. In fact, Babacan himself acknowledged this during a speech at the IMF/World Bank conference in Istanbul in 2009, promising that the government would now jump-start the reform agenda.

It turned out the reforms Babacan had in mind were recent laws like the new commercial code and capital markets law. These regulations, despite some shortcomings, are indeed major improvements over previous versions. As Babacan mentioned, the government also filled holes by introducing non-existing laws on angel investors and venture capital. However, I do not see these as priorities.

The international business community seems to agree with me. According to global professional services firm Ernst & Young’s foreign direct investment (FDI) attractiveness survey, unveiled at their Strategic Growth Forum in Istanbul on May 8, “businesses are more likely to invest in Turkey if it improves its education system, boosts innovation and makes its tax administration more efficient.” These have also been found in academic studies on Turkey’s binding constraints to investment and are mentioned again and again by expat CEOs.

Babacan did not have much to say on any of these, simply because not much has been done other than distributing tablets to kids, which will, according to experts like Sabancı University’s Education Reform Initiative, not have a major impact. You could argue that these are relative criteria; Turkey could attract FDI if it simply fares better than peers. Unfortunately, that is not the case at all.

Turkish students are at the bottom in the OECD’s PISA exams for 15-year-olds. Perennial optimists would mention Turkey’s jump in the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness rankings, but looking at the details reveals that the improvement is mainly thanks to macroeconomic performance. In fact, the country’s rank fell from 62 to 72 in the World Bank Doing Business survey.

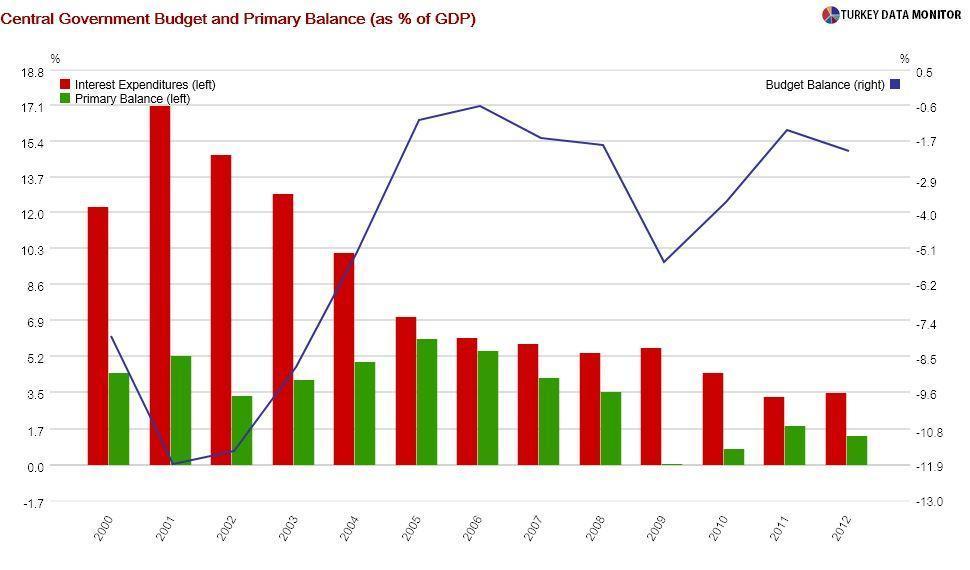

The reform agenda was not the only point I would contest in Babacan’s speech. The economy czar also argued that Turkey was running a tight fiscal ship. It is true that the both the budget and primary balance, which excludes interest expenditures, improved significantly after 2010, but these measures are related to the strength of the economy. After all, tax revenues rise, and automatic stabilizers like unemployment benefits decrease when the economy is doing well. The IMF has looked at the cyclically-adjusted deficit and argues that fiscal policy was not particularly tight from 2010 to 2012.

Just so that we get the facts straight…