Four facts on growth you won’t find elsewhere

The National Income Accounts released on April Fools’ Day fooled everyone. The Turkish economy

expanded only 1.4 percent in the last quarter of 2012, surprising economists who were expecting a figure of 2-2.5 percent.

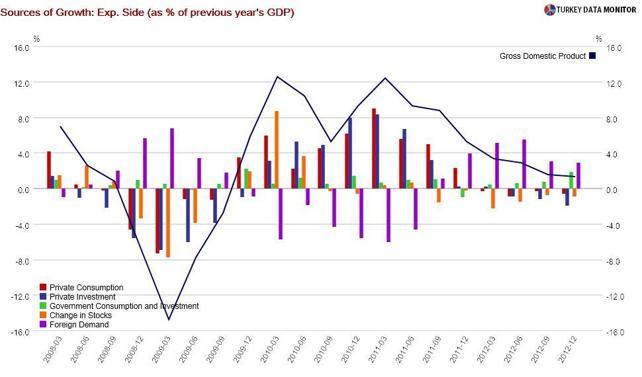

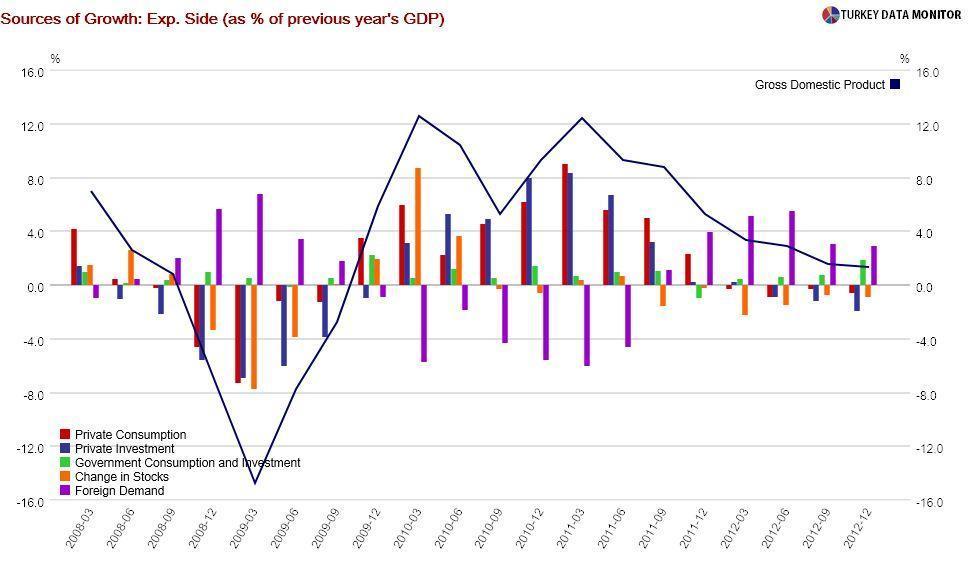

External demand drove growth, as domestic demand was dismal. Government spending was somewhat able to offset private consumption and investment. Finally, the low base of last year and the depletion of stocks hint at a stronger bounce-back this year. But the likely stock build-up could result in price pressures.

But rather than go over the nitty-gritty details of Monday’s figures, I would like to discuss the longer-term implications of the data. I got

a lot of positive (and

some negative) feedback to

Monday’s column, and so I will stick with the same theme, going over four facts I haven’t seen in most research reports on the growth data.

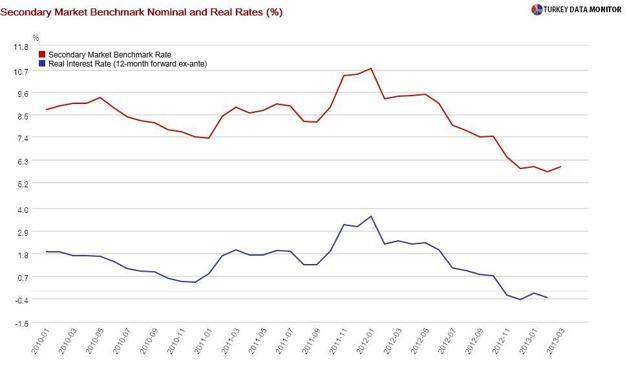

First, simple algebra reveals that of the roughly 3.5 percent decrease in the Gross Domestic Product in the current account deficit this year, about 1.5 percent came from the fall in investment and 2 percent from the rise in savings. As Central Bank Gov. Erdem Başçı underlined during a speech in Mardin on April 3, Turkey needs to increase its savings rate further to keep its deficit under raps when the economy recovers. But I don’t think that is feasible with negative real interest rates.

Why did savings increase last year? It seems the well-known relationship between capital flows and growth broke down, which is my second observation. A casual look at the Central Bank’s balance sheet reveals that some of the flows ended up at the Central Bank as partial bank reserves instead of being transformed into credit, as banks utilized the

Reserve Option Mechanism, preferring to hold some of their required reserves as foreign currency.

Third, the growth numbers would have been worse had tourism statistics not been updated. While it is almost impossible to calculate the impact of the

$5.9 billion 2012 revision on growth, a back-of-the-envelope calculation hints that growth for the whole year, which turned out to be 2.2 percent, could have ended up less than 2 percent.

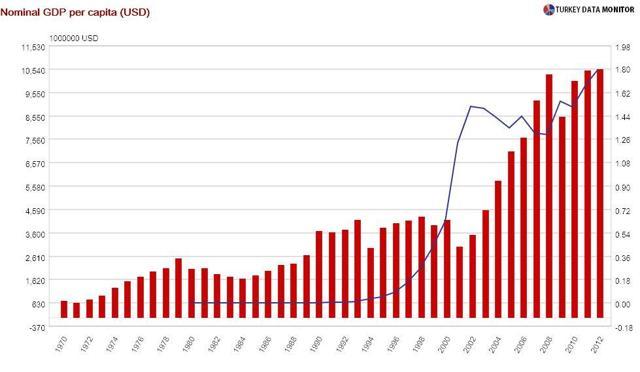

Last but not the least, the impressive increase in Turkish per capita income seems to have stalled: After hovering around $4,000 in the 1990s, GDP per capita surged after the 2001 crisis, but it has been stuck around $10,000 since the global crisis. It is true that the exchange rate played a role in this increase, but it is impossible to overlook the impact of the economic recovery program enacted after the 2001 crisis and the macroeconomic stability that followed.

This phenomenon is not specific to Turkey. There is actually quite a bit of literature on the

middle-income trap, which describes emerging markets stuck at an intermediate level of GDP per capita. Why did Turkey get entrapped, and how can it free itself? These warrant a separate column, but we may have maxed out our potential

without structural reforms.

The National Income Accounts released on April Fools’ Day fooled everyone. The Turkish economy expanded only 1.4 percent in the last quarter of 2012, surprising economists who were expecting a figure of 2-2.5 percent.

The National Income Accounts released on April Fools’ Day fooled everyone. The Turkish economy expanded only 1.4 percent in the last quarter of 2012, surprising economists who were expecting a figure of 2-2.5 percent.