Food (prices) for thought

Farmers from the U.S. to the former U.S.S.R. have suffered from severe drought this summer. As a result, food prices soared 6 percent in July, after three months of decline.

Farmers from the U.S. to the former U.S.S.R. have suffered from severe drought this summer. As a result, food prices soared 6 percent in July, after three months of decline.The United Nations reported on Thursday that its food price index had remained steady in August. This development may calm nerves a bit, but the most popular question posed to me by readers and clients in the past two months, after those about Turkish monetary policy, has been whether this global food price surge would affect domestic inflation.

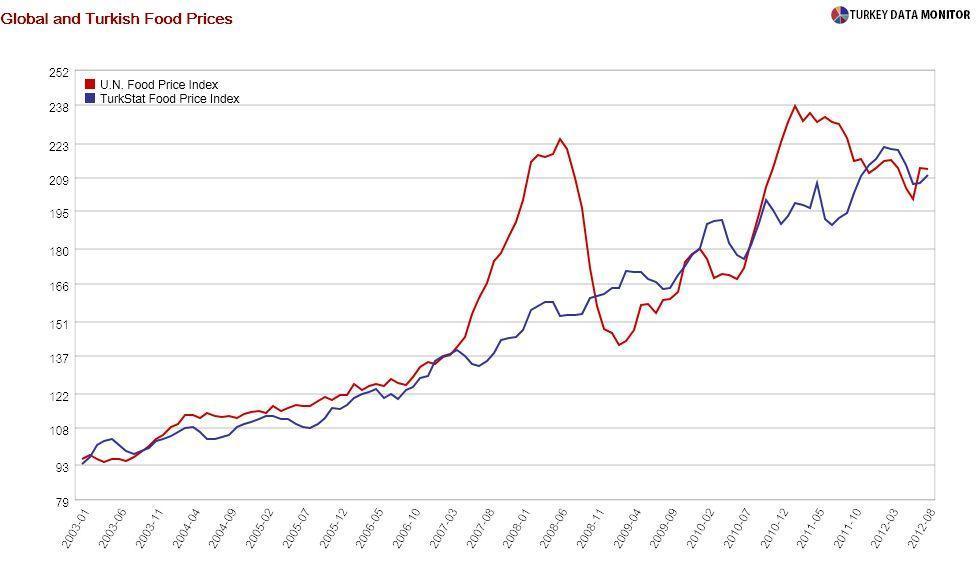

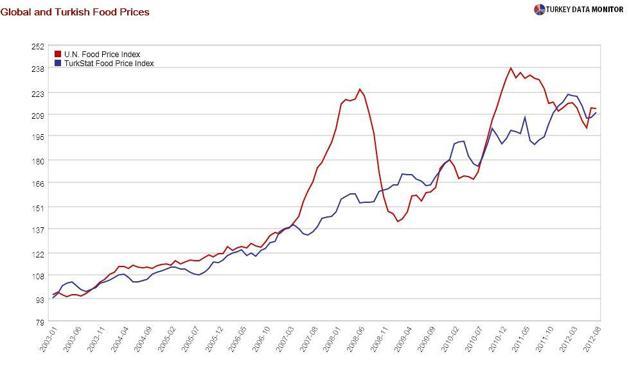

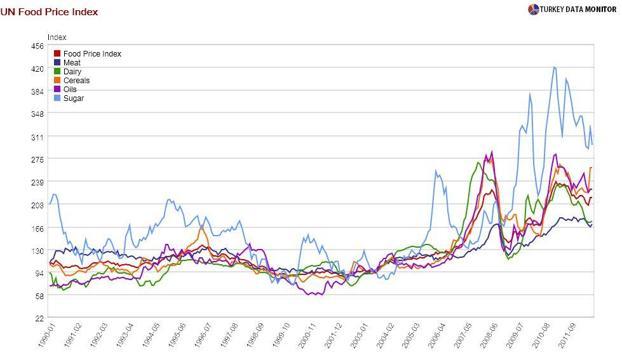

This is a very logical question. After all, food makes up almost one-fourth of the consumer price index basket, from which inflation is calculated. And a first look hints that global and Turkish food prices pretty much move together.

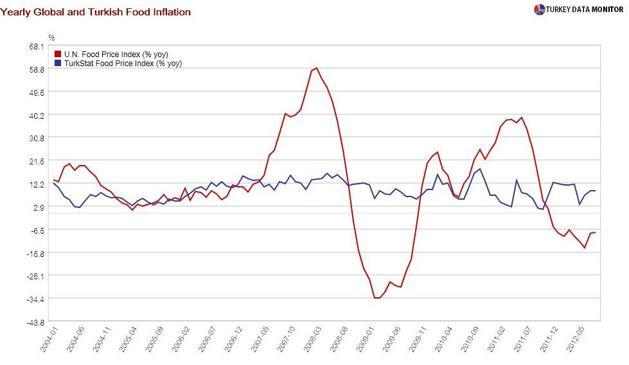

But looks can be deceiving. For one thing, Turkish food prices did not surge in the 2008 and 2010-2011 food crises, when global prices jumped more than 10 percent in a couple of months. And when you actually look at inflation rather than prices, the relationship weakens, which is confirmed by formal statistical tests.

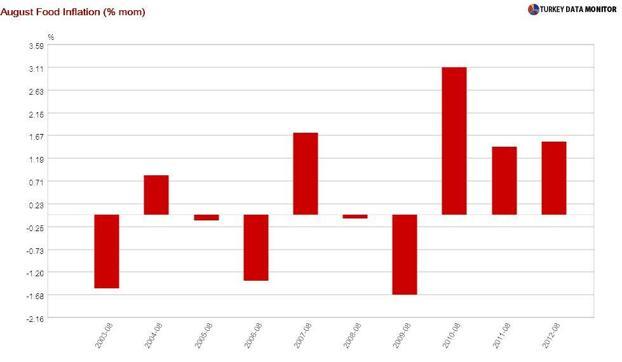

In fact, a quick review of the last two months’ inflation suggests that my readers’ worries may be misplaced. While monthly July food inflation was significantly higher than in previous years, most of that was due to Ramadan, when food prices traditionally rise. In fact, August food inflation was almost the same as last year’s.

But didn’t I just say that looks can be deceiving? Citi’s Turkey economists show that global food prices spill over to the domestic economy with a lag and over time. They predict that Turkish headline inflation will increase by 0.50-0.85 percentage points as a result of the food shock. Since this effect will be spread over the course of several months, they project the impact on end-year inflation to be 0.4 points.

The key question is whether the Turkish Central Bank would (or should) respond if Citi’s analysis turns out to be right. They would not. For one thing, as I argued last week in my blog, inflation is now playing second fiddle to capital flows when it comes to Turkish monetary policy.

Moreover, most economists believe that the best response to a supply shock is no response. In fact, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s own research indicates that the most damaging aspect of supply shocks is a central bank’s contractionary response, rather than inflation. Turkey’s Central Bank has noted several times that it thinks the same way.

More importantly, global food prices may continue to hover at high levels. In the short run, liquidity actions by the major central banks could support commodity prices. The Economist Intelligence Unit expects prices to remain elevated, as they believe that “the recent ultra-dry conditions will linger, negatively affecting prospects for next year’s crop”.

I am more worried about the longer run, as global food prices have risen considerably during the last decade. There may be structural factors at play here. For example, the supply of global grains stocks has fallen from 125 to 75 days since 1985. You can see a similar pattern in many other food items.

But don’t worry, be happy: After all, as John Maynard Keynes said, “in the long run, we are all dead”.