Food for thought

At 0.1 percent monthly, Turkey’s August inflation, which was published on Sept. 3, disappointed again by coming in slightly higher than expectations of 0 percent. Annual inflation rose from 9.3 to 9.5 percent.

At 0.1 percent monthly, Turkey’s August inflation, which was published on Sept. 3, disappointed again by coming in slightly higher than expectations of 0 percent. Annual inflation rose from 9.3 to 9.5 percent.In its regular note on price developments published on Sept. 4, the Central Bank put the blame on food inflation, as expected: In an interview on news channel NTV on Sept. 2, economy tsar Ali Babacan noted that Turkey was facing the worst drought in 14 years. According to a graph that Governor Erdem Başçı and other Bank officials have often used in their recent presentations, there have been only three other similar episodes in the last four decades.

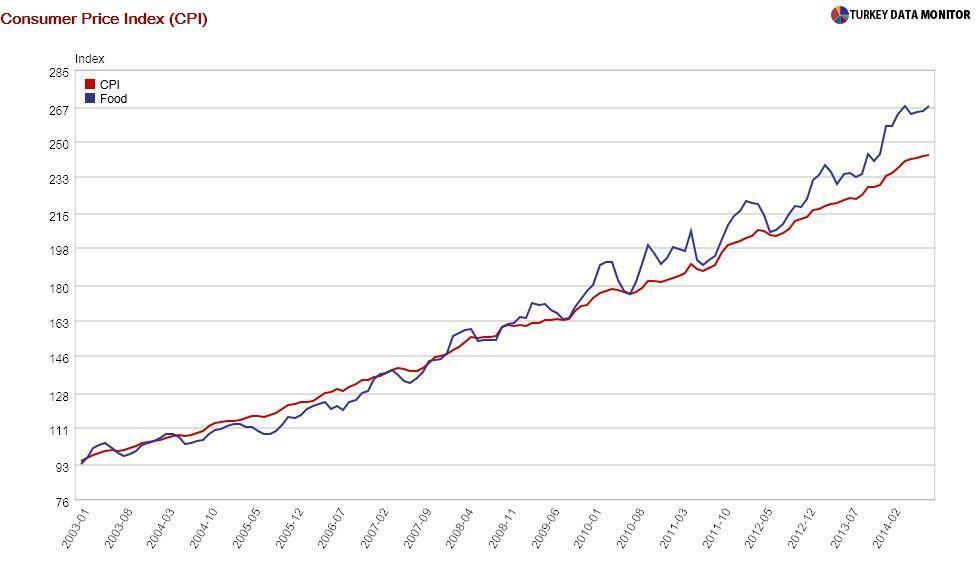

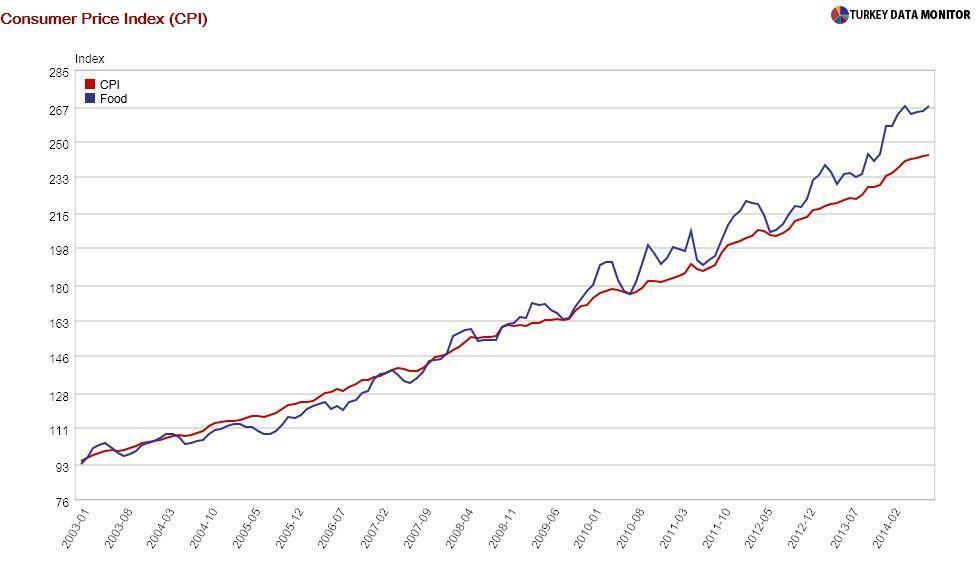

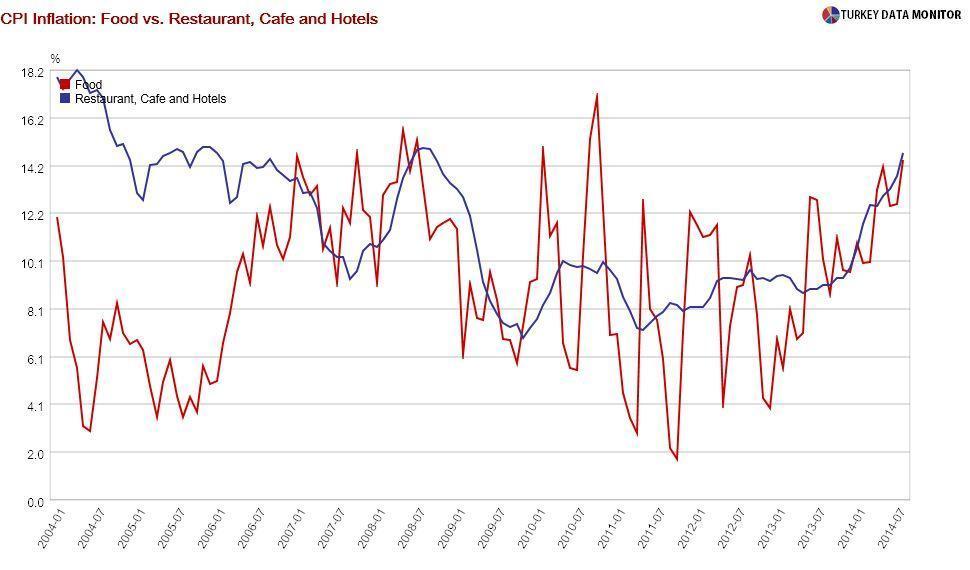

While unprocessed food prices have been increasing more than the rest of the consumer price index since late 2008, the divergence has become more pronounced recently. As the Central Bank’s chief economist Hakan Kara noted during his presentation at the Bank’s monthly meeting with economists on Aug. 28, food prices also have an indirect impact on headline inflation though some service items such as catering.

I agree with the Bank that food inflation cannot be addressed with monetary policy. One solution could be trade: While international food prices have generally fallen sharply during the summer, domestic food prices have risen further. Başçı and Kara are right to underline that “an active foreign trade policy to be imposed on certain agricultural products could be effective in curbing the upside risks on food prices.”

Trade could also improve domestic markets. The Union of Agricultural Chambers (TZOB) recently released monthly changes in producer and consumer prices for certain items. For some items, consumer prices rose much more than producer prices, for others much less. While the myth of the evil middlemen taking advantage of the drought is not supported by the data, buying food for our family business three times a week, I experience the volatility in food prices first-hand.

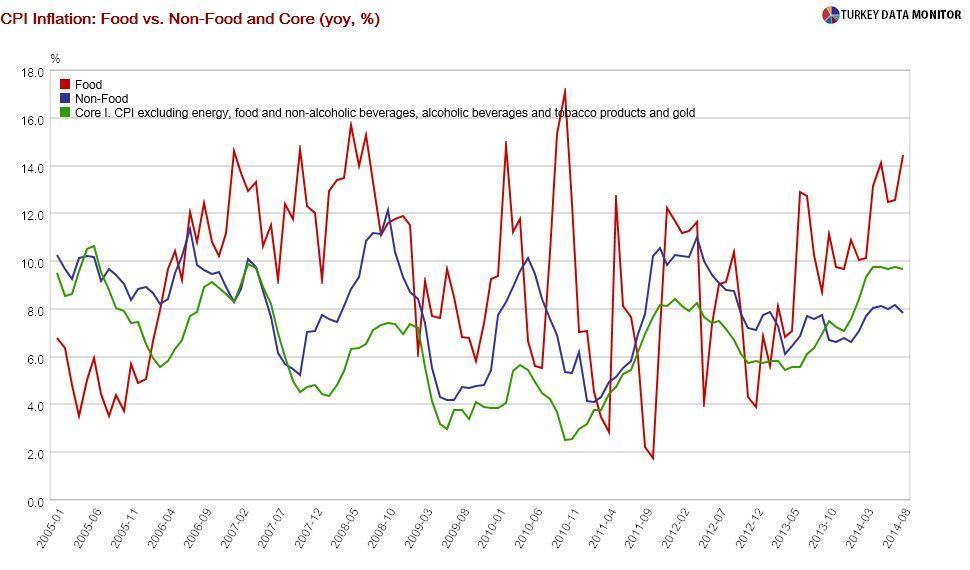

However, contrary to what the Bank and many market economists claim, there is much more to August inflation than the drought. For one thing, non-food inflation fell only slightly in August. Besides, the Central Bank’s favorite measure of core inflation, which excludes food, beverages, tobacco and gold, has been hovering just below 10 percent since April.

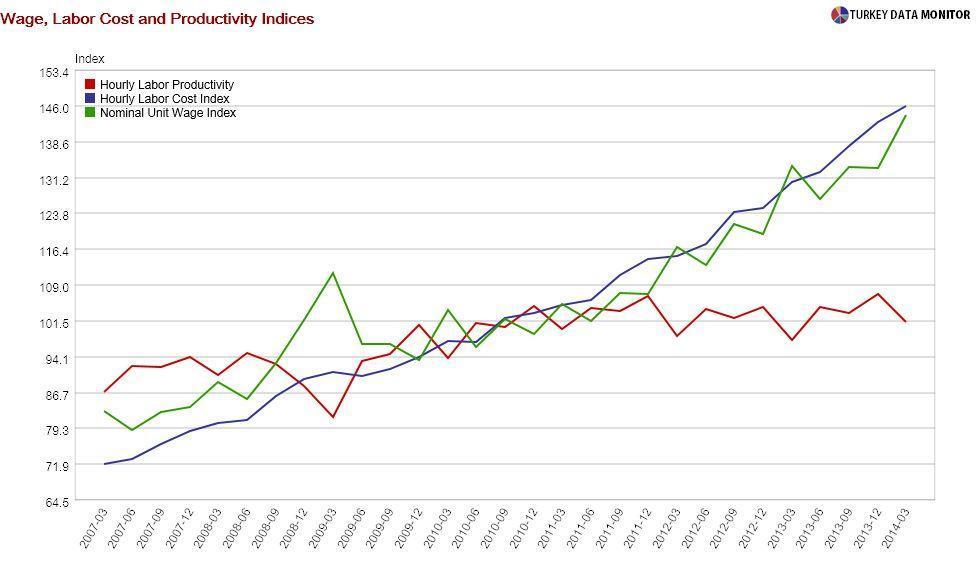

In any case, a similar point could be made for general prices, not just food. For example, wages and labor costs have risen much more than productivity since 2011, mainly because productivity has stalled. As a result, producers feel compelled to raise their prices. Monetary policy cannot address this problem; structural reforms can.

However, monetary policy can address demand-based pressures, which the Central Bank created in the first place: The most recent leading indicators, such as the CNBC-e consumer confidence and purchasing managers’ indices that were released on Sept. 1, are hinting that the economy has started picking up towards the end of the summer after a soft second quarter. Therefore, it is time for the Central Bank to stop cutting interest rates.

But I am not sure if Başçı will be able to resist President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his inner circle, who need more growth and believe that higher rates cause more inflation. At least Babacan is still here to back up Başçı.