Demystifying Erdoğanomics

I was planning to take on Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s claim that

high interest rates beget high inflation - until I realized that I would be wasting my (and your) valuable time.

Not that I think it makes sense. It is a crazy idea all right, even though it was even voiced by a Fed president in 2010. It actually

recently resurfaced, causing a debate in the blogosphere. But Erdoğan is not asking for lower rates to combat inflation. A cursory look at the latest data will give you some clues on his objective.

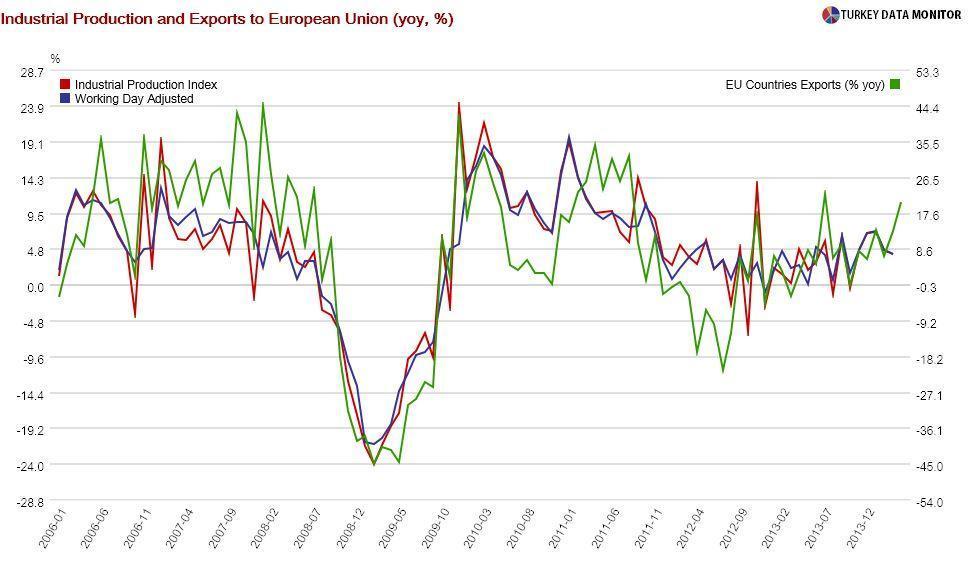

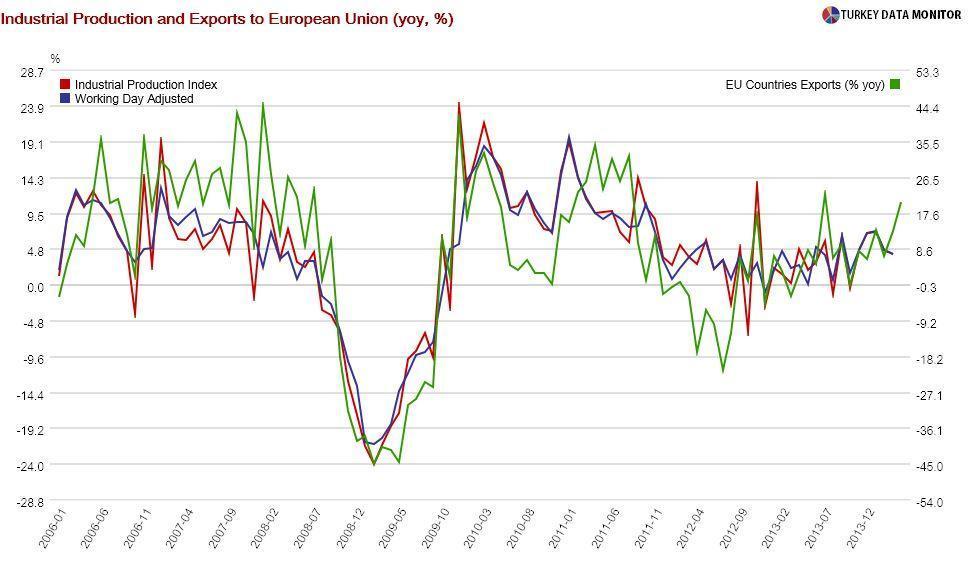

Things do no look bad on the production side. Industrial production was

strong in April, mainly thanks to exports. In a recent research note, Istanbul think-tank

Betam argued that growth would get a boost from exports to Europe, which rose 20.5 percent annually in April,

according to official data released on May 30.

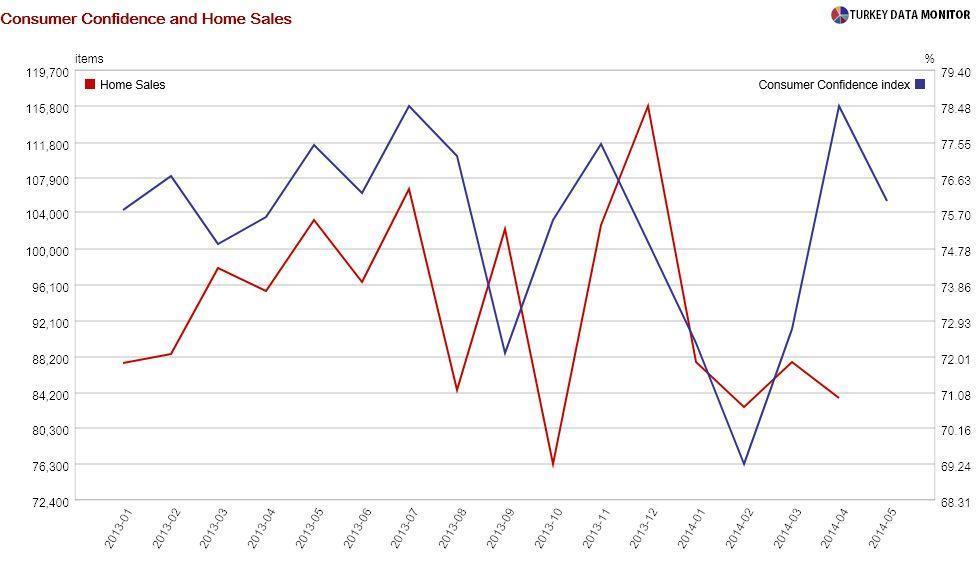

However, consumption is an entirely different story. Having plunged after the graft scandal, consumer confidence had recovered in March and April. But it

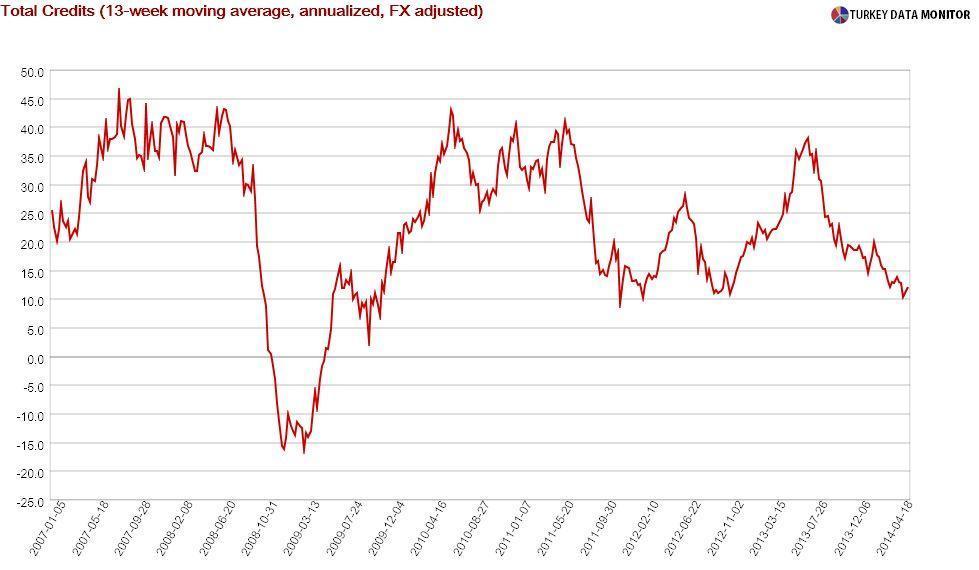

fell again in May and remains low. Credit growth is still weak. According to a recent report by real estate data company REIDIN, there is an oversupply of 1 million homes.

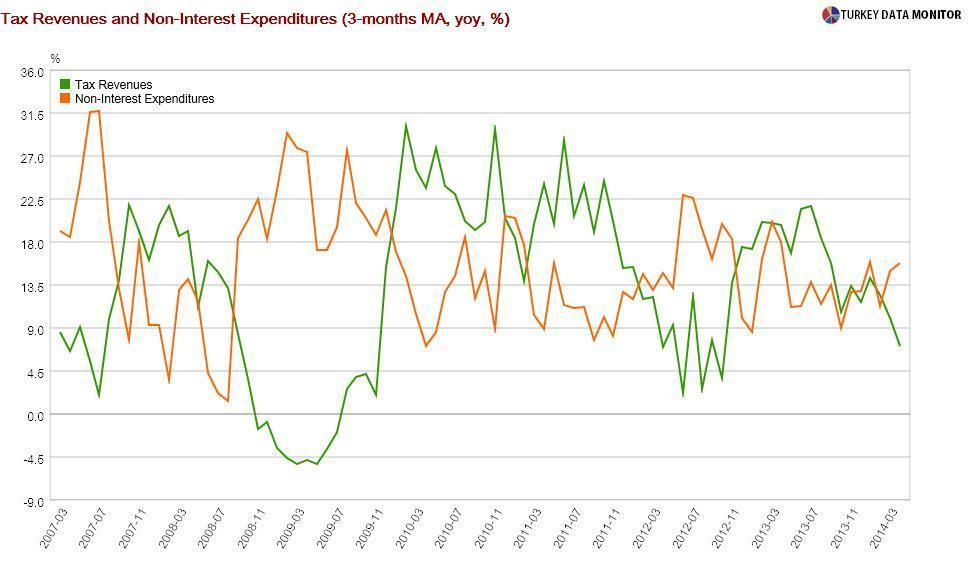

Erdoğan apparently would like to boost domestic demand to ensure that he is elected President in August. I guess the

pork barrel spending he kicked off before the local elections, as evidenced by the growing wedge between revenues and non-interest expenditures, is not enough. Will it work? For one thing, it takes at least 3 months for Turkish monetary policy to be effective. A major rate cut at the next rate-setting meeting on June 24 would be too late.

Besides,

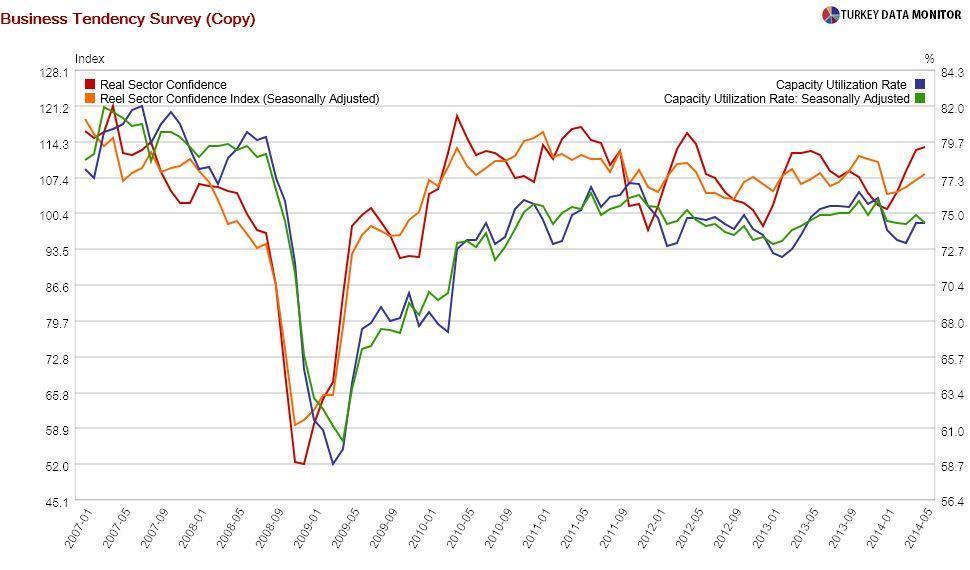

unlike in the movies, if you build it, they won’t come: If consumers don’t have a lot of purchasing power or confidence in the economy, they won’t buy even with zero real rates. As for businesses, capacity utilization is still low. Would they undertake new investment just because loan rates have fallen if they had a lot of spare capacity?

On the contrary, given the country’s large external financing requirement, premature easing could revive depreciation pressures and risk a

sudden stop in capital flows. This could cost Erdoğan the Presidency, not half a percentage point fall in growth or rise in unemployment. And even if lower rates do not have a direct impact on inflation because of the slack in the economy, a weaker currency would raise inflation through import prices.

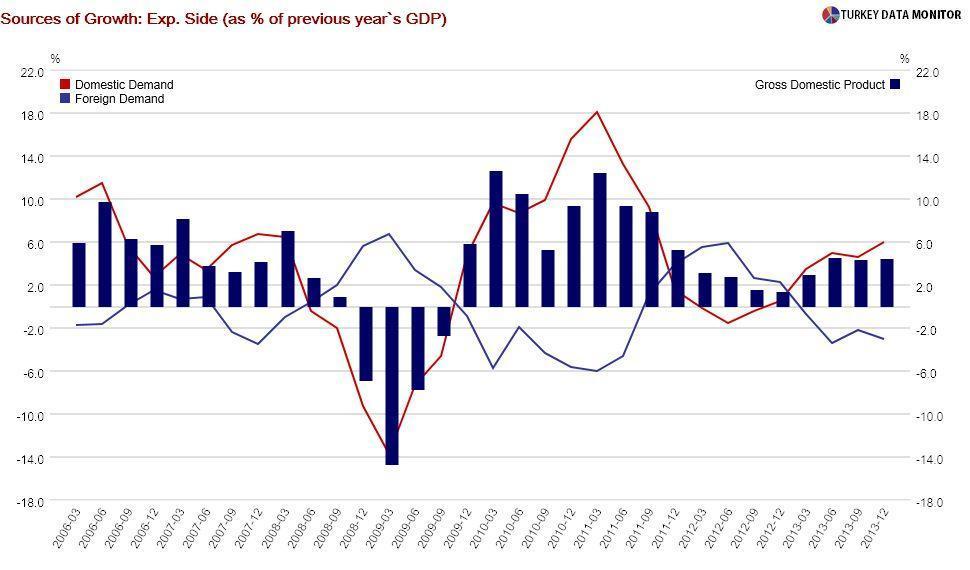

Even if all goes well, Erdoğan would be disrupting Turkey’s much-need economic rebalancing. The Turkish economy needs to shift from domestic to external demand as the main engine of growth and reduce its large current account deficit- the country’s Achilles’ heel. This adjustment has already started, but boosting consumption and imports with lower rates would reverse it.

Erdoğan will probably get what he wants, and Turkey will once again be left to the whims of global sentiment. I would therefore advise you to be very cautious on Turkish assets until the elections. All I am asking for this valuable advice is for you to

#RememberBerkin,

#RememberEsther and

#RememberSoma- although I would be very grateful if you contributed to

the fund Esther’s friends set up for her and her 18-month old son.

As for Erdoğan’s interest rate-inflation theory, I am merely passing it along to Japanese policymakers, who have been struggling to inflate their economy for more than two decades. Who needs

Abenomics when Erdoğanomics can deliver inflation simply by raising interest rates?

I was planning to take on Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s claim that high interest rates beget high inflation - until I realized that I would be wasting my (and your) valuable time.

I was planning to take on Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s claim that high interest rates beget high inflation - until I realized that I would be wasting my (and your) valuable time.