An economist’s view of the 'fezlekes'

Ten hours is a long time to spend sitting in a seat.

Since I didn’t have much to do, I decided to read the 400-page report that was supposed to be the investigative files (fezlekes) on graft allegations about four ex-ministers during my flight from Istanbul to Johannesburg.

I am saying “supposed to” because I cannot be sure if the documents I read are genuine or not: After

heated debates in the extraordinary parliamentary session on March 19, the call for a general discussion on the files was rejected by deputies of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

According to the titles of the allegations, which were the only parts of the files that were read, ex-Ministers Muammer Güler, Zafer Çağlayan and Egemen Bağış are accused of “taking bribes more than once.” Güler and Çağlayan are also charged with “arranging fake documents.” Ex-Minister Erdoğan Bayraktar is accused of “using his influence for others’ gain and jobbery.”

Although I cannot confirm they are the real documents under these titles, the files I read were extremely interesting. First of all, I could not help but admire, as an economist, the economic genius of

Reza Zarrab, the principal bribe-giver according to the documents.

To make a long-story short, Zarrab devised schemes to bypass the embargo on Iran. For his services, he was getting 3 percent of the total money flows, one-third of which he was then passing on to Çağlayan and Halkbank General Manager Süleyman

“Shoebox” Aslan. This way, his and their incentives were aligned. Moreover, Çağlayan made life difficult for Zarrab’s competitors, turning him into a monopoly.

Zarrab’s methods of getting money into Iran were equally ingenious: He first exported gold from Turkey and Dubai to Iran. When this arrangement caught the attention of U.S. and international authorities, he resorted to “pretending to export food and medicine,” which were exempt from the embargo, from Dubai to Iran.

As he was dealing with billions of dollars, Zarrab needed protection. Who would be better to provide it than the interior minister? Güler delivered all kinds of services such as granting Zarrab’s men Turkish citizenship, banishing “uncooperative” bureaucrats and in general covering up his illegal activities.

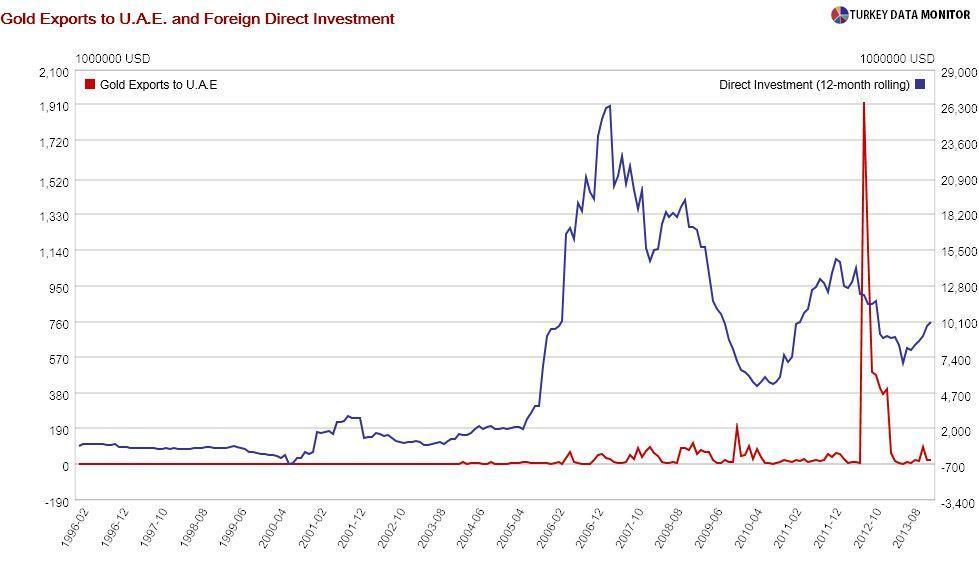

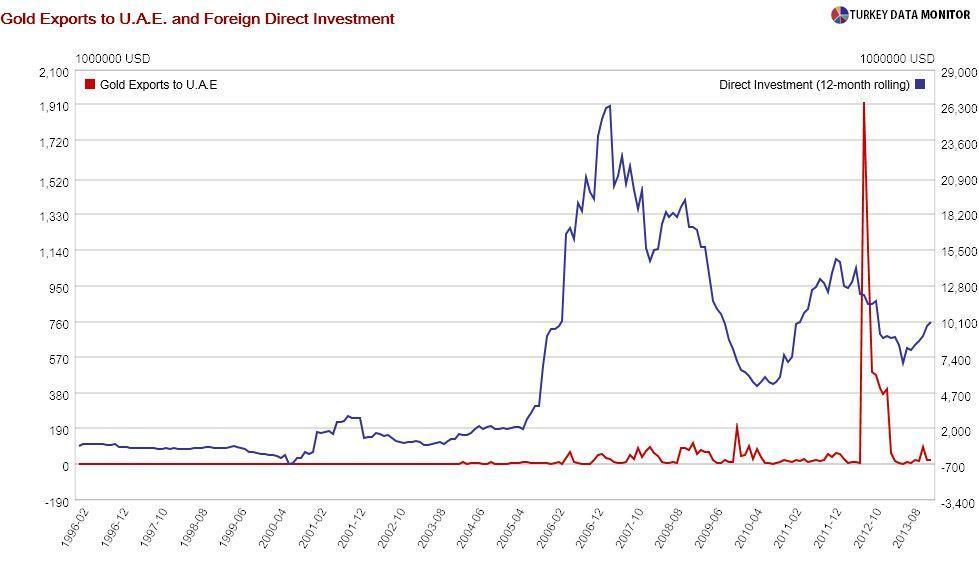

There is also another economic angle to this story. Deputy Prime Minister (and economy czar) Ali Babacan recently noted that a country where there aren’t rules but discretion will not be able to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). He was only partially right.

Legitimate companies will indeed think twice before investing in such a country: Unlike many peers, FDI to Turkey did not pick up after the global crisis. It will, however, be a haven for the likes of Reza Zarrab.

After all, could you rig the law to your benefit in any country with rule of law, as Azerbaijan’s state oil company SOCAR is suspected of doing? – at least according to

an article that appeared in EurasiaNet on March 19.

I may tell that story one day, but only if you continue to

#RememberBerkin!

Ten hours is a long time to spend sitting in a seat.

Ten hours is a long time to spend sitting in a seat.