A very standard and poor reaction

That’s

exactly how I felt about the

government’s response to the rating agency Standard and Poor’s (S&P) downgrade

of Turkey’s

sovereign credit outlook from positive to stable.

Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan opened the show, but it was Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan who stole it with amusing comments I summarize at my blog. The less temperamental Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek decided to engage in a more scientific debate by questioning the agency’s debt figures, and S&P issued a note to clarify. He also emphasized that Turkey’s debt was lower than several crisis-stricken countries rated above Turkey.

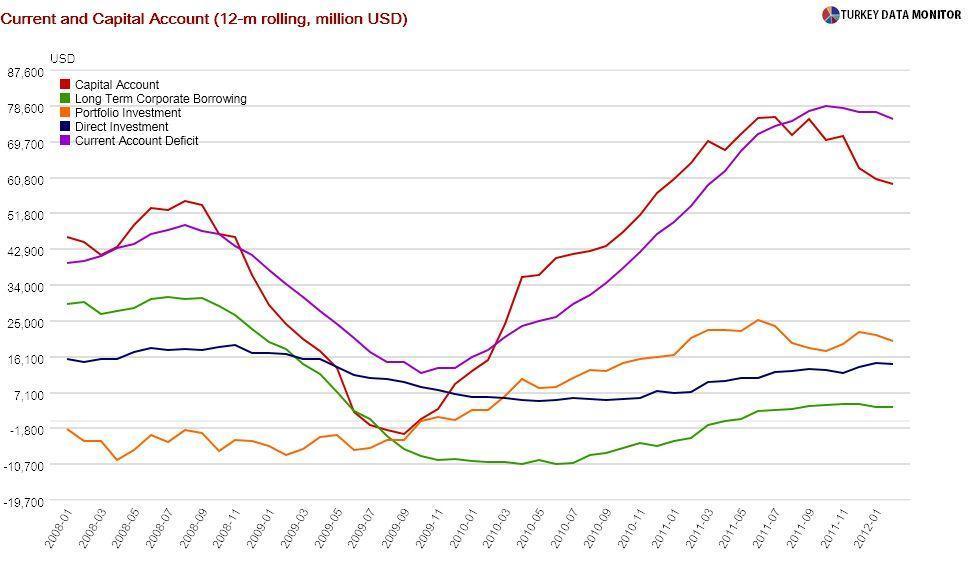

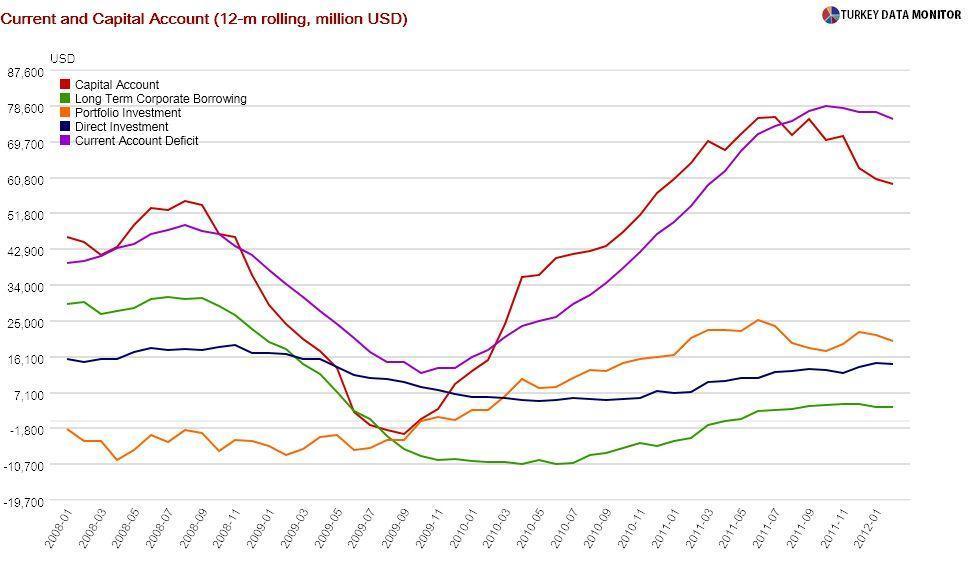

But debt is only one of the variables S&P bases its decision on. There is also the current account deficit, and although the Central Bank is claiming otherwise, neither the quantity nor the quality of its financing is improving. Foreign direct investment has crept up because of one-off deals, and corporate borrowing is improving after negative figures during the crisis, but fickle portfolio flows still make up a sizable share of the capital account. And if capital flows are abundant, as the Bank hopes, the economy will become yet more vulnerable to a reversal, as S&P underlines.

In a video

released along with the decision, primary Turkey credit analyst Eileen Zhang

notes that they also look at per capita income. Turkey’s GDP per person is half

of Portugal’s and one third of Italy’s, as reflected by low

productivity and women’s

labor force participation. That’s why Royal Bank of Scotland’s Tim

Ash suggests that Turkey’s willingness to pay its debts, i.e. its track

record, should be taken into consideration, implying a change to the agency’s

methodology.

Many were also surprised because the S&P announcement came right after March trade figures hinted that the long-awaited current account adjustment had begun. But as I argue in my blog, those figures may be deceptive. Besides, “less-buoyant external demand and worsening terms of trade could inhibit Turkey's economic rebalancing”, as S&P notes.

During a phone chat on Friday, Zhang explained this statement, citing global liquidity, external demand and oil prices as the key risks in the next 12 months. S&P has decreased their 2012 growth forecast for the Eurozone from 0.4 percent in December of last year to no growth in April. These more pessimistic projections are undoubtedly having an effect on Turkey's outlook.

Zhang is actually more optimistic on the Turkish economy than me: She also noted that “Turkey was doing relative well on policy effectiveness, moderate indebtedness and monetary policy flexibility”, which “give Turkey the fiscal space and flexibility to deal with potential external shocks”.

Besides, the Turkish fury to the downgrade was really much ado about nothing. Zhang underlined that Turkey was one of the last European countries to lose the positive outlook. Although I did not pursue this with her, the decision may have been technical: A positive outlook would have meant the possibility of a ratings upgrade in the near future, which is not realistic given the global uncertainties and Turkey’s own vulnerabilities.

But then again, we are a temperamental bunch.