Turkey is becoming a victim of circumstantial evidence

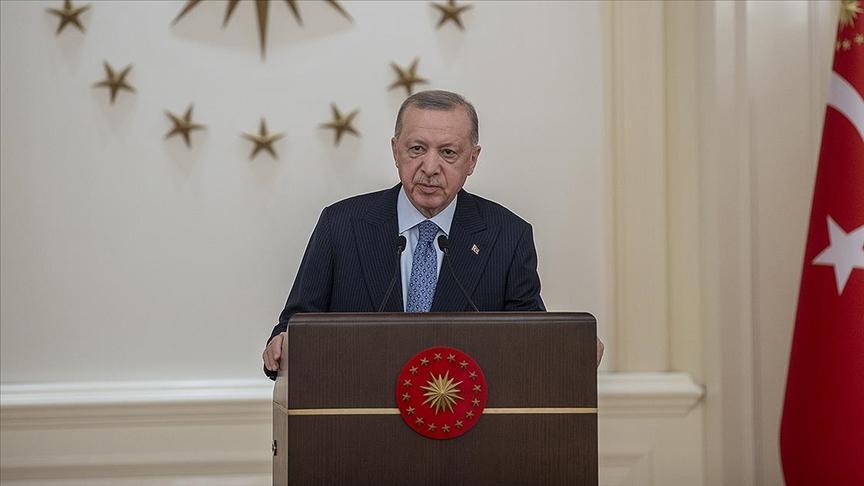

Just 24 hours after the failed coup attempt of July 15, 2016, some Western colleagues were convinced that it was all a charade staged by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

While we in Turkey were trying to understand what had really happened, some colleagues in the international media had already diffused the fog and solved everything. They had two pieces of “evidence”: Erdoğan’s track record and the clumsy way the coup was staged.

It was certainly no secret that Erdoğan’s anti-democratic steps aimed to change Turkey’s system to one-man rule. A failed coup helped Erdoğan reach that goal, so it must have been staged by Erdoğan.

If this is not circumstantial evidence, I don’t know what is.

The other line of reasoning was that it was bizarre to start a coup at 10 p.m. simply by blocking one side of the main bridge of Turkey’s biggest city. It was apparently not credible for the mighty Turkish military, which had succeeded in toppling many governments in the past, to have failed this time. Therefore the coup attempt must simply have been a charade plotted by the government.

If this is not circumstantial evidence, I don’t know what is.

Indeed, many unanswered questions remain about the events of that night. Did the government know a coup was in the making but kept silent in order to trap the plotters and reveal their true face? Why did the top branches of the National Intelligence Agency (MIT) and the military not take the necessary measures, even though they were tipped off about the coup hours before it started?

These and similar questions still have to be answered and officials have to be made accountable, especially because of the death toll that evening.

But while these unanswered questions may create clouds of suspicion, they are certainly not enough to conclude that Erdoğan staged the coup attempt.

Within a month of the coup, around 70,000 people had been detained, sacked or suspended from their jobs. This prompted skeptics to ask how “Erdoğan” could have found out about the culprits so quickly. But what we did not know back then was that the MIT had already cracked the secret communication network of the Gülenists, therefore finding out who was using the encrypted chat application ByLock. It thus held a list of suspects in its hands.

When MIT cracked ByLock, it could not hold its users accountable for any crimes. But the coup attempt a few months later actually provided them with a justification.

Some skeptics have used other means to pin the coup attempt to the Erdoğan government. They sometimes note that Gülen-linked prosecutors launched a corruption probe into government officials in operations between Dec. 17 and Dec. 25, 2013. As Erdoğan felt threatened by such moves, he staged a coup to eliminate those who he saw as a threat. But isn’t this also circumstantial evidence?

There is no doubt that Erdoğan and his advisors have committed - and continue to commit - crucial mistakes that are making the fight against the Gülen network tremendously difficult. For example, instead of defining the network as a terrorist organization, they could have defined it as a criminal organization, which would have made the government’s life a little less difficult abroad.

Instead of considering all members and sympathizers of the network as terrorists, they could also have distinguished between different layers, differentiating an executive core from people who simply had an account in a Gülen-affiliated bank. A general amnesty for the outer layer of the network could have facilitated the struggle against it, rather than creating a hostile group for which no option was left other than to flee abroad and stay loyal to Gülen.

What’s more, anti-democratic targeting of non-Gülenist critics of the government continues to be a terrible mistake, highly detrimental to the fight against the Gülenists.

But all the mistakes of the government should not overshadow the vicious face of the Gülenists. Turkey’s Western allies ask for direct proof, accusing Turkish officials of relying on circumstantial evidence. They deny their ally Turkey the benefit of the doubt, while the benefit of the doubt is extended for what Ankara considers an existential threat and an enemy.

Why is this? One possible explanation is that Turkey is led by Erdoğan, who few in the West either like or see as an ally. They therefore prefer to side with the Gülenists, relying on circumstantial evidence to argue against his wrath.

Turkey’s Western allies may have many credible reasons not to like Erdoğan. But this dislike should not come at the expense of turning a blind eye to the vicious face of the Gülen network.