Green with Envy

Aylin Öney TAN - aylin.tan@hdn.com.tr

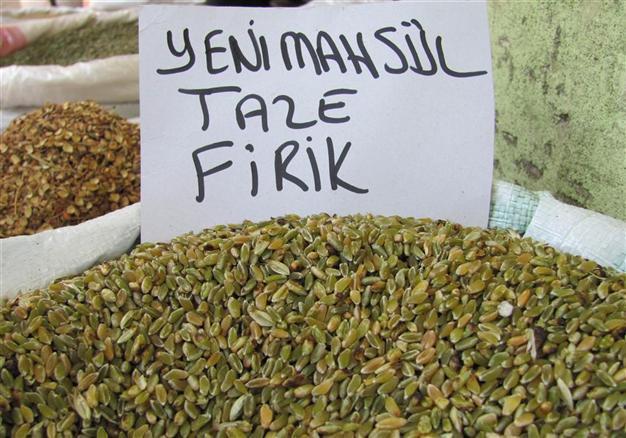

Grains are staple foods for mankind. Wheat and rice are particularly important to Turkish cuisine, both widely enjoyed and used. Throughout history rice was considered finer, and more prestigious, hence its taking place as the staple of the elite, and the humble bulgur made from wheat has served as the sustenance of the masses. Cooked in countless ways, both are delicious, but if there is one grain that should make both green with envy, that is definitely “firik,” or unripe green wheat.

“Firik” in Turkish, usually written in English as freek, freekeh or farik is actually unripe green wheat parched in the field and then dried. It is very complex in flavor, both rich and fresh, with strong smoky notes, making it a very intriguing taste to explore. It is a sort of bulgur in a way, cooked before it is dried, but unlike bulgur, which is wheat berries husked, boiled, dried and then cracked, the dish is prepared without boiling but, roasting over fire. The moment that “firik” is made is very critical. The wheat should be picked still green but just ripe, at the moment just when it turns yellow, usually in May. The grains at this stage are still milky and creamy inside, and the whole point is to capture the wheat at this milky stage, while it’s young and tender. The enzymes are deactivated by the parching process, and as the maturation slows downs, the proteins in the wheat do not turn into starch. The moisture-saturated, young grain would be rotten if not dried, through smoking it. Consequently, “firik” is much higher in protein content compared to fully matured wheat products, and way lower in starch, making its glycemic index considerably lower.

“Firik” is usually made with grains of durum wheat, (Triticum turgidum var. durum)

Late spring, or early summer is the ideal season to harvest wheat that will then be used to make “firik”. The wheat stalks are arranged in bundles, left to dry out for a day in the field. Later, these piles are set on fire make the chaff burn off. The firing stage has to be very carefully monitored to have the entire husk, hay, straw burned but not the seeds. The high moisture content of the seeds, especially of the hard durum grain, protects them from burning straight away but it is just a brink of time or an overly strong flame that ruins the batch. Sometimes the process is carried out in a pit dug in the ground, resulting sometimes in a more intense burnt taste. The next step is to separate the wheat from the burned chaff. The grains are further left in the sun to reduce the moisture content of the seeds. The grains are rubbed off, and actually the original name “farīk”, means “rubbed” in Arabic. The resulting grain can be left whole, or further cracked like bulgur, and it amazingly retains its unripe, greenish hue, despite all the charring and parching. The final aroma is in a way still fresh and milky creamy, with earthy nuttiness, bearing mild to overly strong burnt smoky flavors depending on the method used, or to the degree of the parching. Some very smoky ones are used half and half with bulgur to balance the flavors, but for those who like smoked tastes, it must be used on its own to really be able to savor the burnt goodness. “Firik” is used all over the Middle East, as well as in Northern Africa, in countries like Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria. It can be made into rice, used in soups, or more commonly used in stuffing for vegetable dolmas or for chicken. In Egypt “firik” stuffed pigeon is a specialty. No wonder why it is found in the cuisine of all nations in Mesopotamia, the birth place of wheat agriculture, the first ever recipe making use of “firik” appeared as “farrīkiyah” in an early thirteenth-century Baghdad cookery book, Al-Baghdadi.

Bulgur is becoming the new noble grain, due to its health benefits. Special bulgur types made from ancient wheat varieties are becoming more and more popular; but it won’t be fortune-telling to guess that “firik” will be the next hit ingredient in the culinary world. Young Turkish chefs are giving it a try, exploring its immensely complex flavors.

The forthcoming days of Kurban Bayramı, the sacrificial religious holiday, will be marked as the ultimate meat eating period with lots of lamb dishes. This is the time to enjoy a good bowl of this precious ancient grain, with the ancient tradition of sacrificing animals to God. Actually, it makes more sense to celebrate the grain, rather than slaughtering the animals!

Recipe of the Week: The perfect accompaniment to meat, especially to lamb dishes during the Kurban Bayramı, would be a plain “firik pilavı” (or “firik” and rice). “Firik” can absorb water up to twice or even more of its volume. If you decide to use meat stock, make it an oriental one. Boil lamb bones with a few crushed cardamom pods, a handful of crushed coriander seeds, a stick of cinnamon, a few cloves, salt and pepper. Simmer for an hour or more, skimming occasionally. If you use meaty bones the meat should be falling from the bone, and you can shred those to add to the “pilaf” (rice). To make the bring to boil 2 cups of “firik” in 5 cups of stock or just water, simmer gently over a slow flame, lid covered, for about 45 minutes. When most of the cooking liquid is absorbed, add 2-3 tablespoons of butter. Let it remain a little creamy like risotto, it is better moist, not fluffy like Turkish pilaf.

Bite of the week

Fork of the Week: One of the best “firik” I had recently was at a quite

unexpected place. It was not a traditional place, or a restaurant

serving southeastern fare, but it was in Istanbul, at a very

contemporary, forward new restaurant Gile at Akaretler, just across from

W Hotel. Young chefs Üryan Doğmuş and Cihan Kıpçak are getting their

inspiration from tradition and local produce, and serving them in a

totally new way. Their “firik” served in a little iron pot to go along

with 41 hour cooked lamb shoulder, was simply amazing and worth making a

stop in this new gem in town.

Cork of the Week: The vibrant and

crisp Turasan Emir 2011 can accentuate the earthy nuttiness of Firik

with its contrasting acidic fruity notes. That is what we did when

dining in Gile, which has a good selection of award winning Cappadocian

wines.

Grains are staple foods for mankind. Wheat and rice are particularly important to Turkish cuisine, both widely enjoyed and used. Throughout history rice was considered finer, and more prestigious, hence its taking place as the staple of the elite, and the humble bulgur made from wheat has served as the sustenance of the masses. Cooked in countless ways, both are delicious, but if there is one grain that should make both green with envy, that is definitely “firik,” or unripe green wheat.

Grains are staple foods for mankind. Wheat and rice are particularly important to Turkish cuisine, both widely enjoyed and used. Throughout history rice was considered finer, and more prestigious, hence its taking place as the staple of the elite, and the humble bulgur made from wheat has served as the sustenance of the masses. Cooked in countless ways, both are delicious, but if there is one grain that should make both green with envy, that is definitely “firik,” or unripe green wheat.