Byzantine Breeze

Aylin Öney Tan - aylinoneytan@yahoo.com

Claiming the nationality of certain foods is an inevitable act of patriotism, especially so if the countries in the debate were one part of one entity in their history. That is the case of Greece and Turkey, where the ongoing battle over ownership of baklava, yogurt and a countless number of dishes is crowned by calling Turkish coffee and Turkish delight as Greek coffee and Greek delight. The reality is that both parties have the right to call them their own, as both Turkey and Greece are heirs to the Ottoman heritage and thus to the culinary practices of Ottoman geography. Years of living side-by-side, using the same agricultural lands, cooking with the same ingredients and sharing the same tastes for centuries assure the existence of similar cuisines in both countries. Of course the Ottomans also inherited a lot from the Byzantines, but things get a bit complicated when claiming identity related to Byzantine culture. Greeks naturally jump into this obvious link, while Turks remain reluctant to see themselves in this kinship, as the Byzantines had been their enemy, the one to be conquered, in a way, the other!

Claiming the nationality of certain foods is an inevitable act of patriotism, especially so if the countries in the debate were one part of one entity in their history. That is the case of Greece and Turkey, where the ongoing battle over ownership of baklava, yogurt and a countless number of dishes is crowned by calling Turkish coffee and Turkish delight as Greek coffee and Greek delight. The reality is that both parties have the right to call them their own, as both Turkey and Greece are heirs to the Ottoman heritage and thus to the culinary practices of Ottoman geography. Years of living side-by-side, using the same agricultural lands, cooking with the same ingredients and sharing the same tastes for centuries assure the existence of similar cuisines in both countries. Of course the Ottomans also inherited a lot from the Byzantines, but things get a bit complicated when claiming identity related to Byzantine culture. Greeks naturally jump into this obvious link, while Turks remain reluctant to see themselves in this kinship, as the Byzantines had been their enemy, the one to be conquered, in a way, the other!But is that so? What we eat in Istanbul may well have been cherished by the Byzantines of centuries ago. As I was recently writing a paper on the Gallipoli battle, I was looking at the past of peksimet, the ubiquitous twice-baked dried bread in Turkey, as one of the staple provisions of the Turkish army. And there we had it again, the battle; not the battle in the field, but the battle of claiming ownership of the origins of the poor dried bread. The Greeks were passionate about their paximadi, with various regional versions abundant all over the country. Most are astonishingly similar to gevrek, the tasty thin brittles, especially the anise-flavored ones, available all around in Istanbul bakeries. When a group of chefs from London’s Moro restaurant visited Istanbul a year ago, one chef, Marianna Leivaditaki, who was originally from Crete, was amazed by the similarities she found here. She was repeatedly saying, “Just like my grandmother did!” or “Just like we have back in Crete!” She kept saying that she did not understand a single word in Turkish, but by the body language and the facial expressions she could understand exactly what was being said. Among the foods she found similar were of course the crunchy anise brittles and the soup we think of as quintessentially Turkish, tarhana. This soup is another one of continuing debate: Greek or Turkish? Greek trahana is similar to most regional Turkish ones; the one she tasted in Istanbul brought her straight into her grandma’s kitchen. She was flabbergasted to find her childhood memories in a city that she has never visited before.

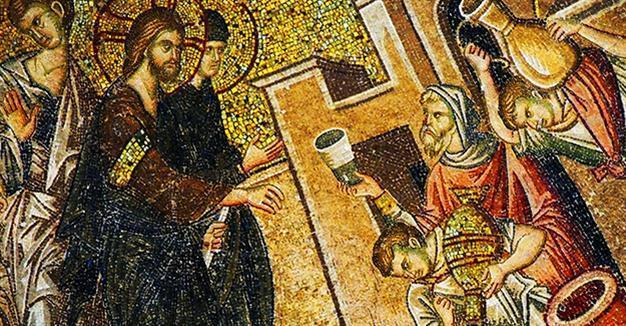

I was recently trying to create the menu for the gala dinner of the forthcoming Byzantine symposium in Istanbul. Recreating historic dishes is complicated and can be erratic; instead I named the menu “Byzantine Breeze” and chose to trace remnants of Byzantine food in Istanbul, with inspirations from the Byzantine period. To my surprise the traces of the Byzantine culinary legacy were plenty. From cured and salted sardines, anchovies and bonito to an amazing variety of olives or the amazing cornucopia of fruit pickles like unripe melons and watermelons, white cherries, jujube, greengage, apricots, unripe peaches and almonds, snake cucumbers, hawthorn and medlar, Byzantine tastes were everywhere, on every corner. It will be a thought-provoking dinner for the symposiasts; while thinking of “the other” of five centuries ago, we might find that “the other” is still with us, here and now!

Bite of the Week

Event of the Week: If you are interested in finding out about Byzantine culture, reserve your days for June 23-25 and follow the 4th International Byzantine Symposium at Anamed, the Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations in Beyoğlu, Istanbul, İstiklal Caddesi No: 181. The International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium is held every three years in memory of late Sevgi Gönül, who helped further scientific research on the Byzantine period in Turkey and contributed greatly to the society-wide enhancement of the awareness of Byzantine heritage. This year is dedicated to identity and the other, titled “Byzantine Identity and the Other in Geographical and Ethnic Imagination.”

Fork of the Week: Safrantat, the renowned Turkish delight and confectionary maker in Safranbolu, makes an amazing yaprak helvası, literally translated as leaf halva; a layered nougat of walnuts. İbrahim Canpulat, the owner of the outstanding boutique hotel Gülevi, argues that it is incredibly similar to gastris mentioned in ancient texts. İbrahim is an architect like myself and one the most curious persons I have ever met. He traces the culinary backgrounds of his region trying to find the roots of local dishes. The best is to pay a weekend visit to Safranbolu, stay in Gülevi, enjoy its magic tranquility, and visit the old town, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Do not forget to stroll around the Saturday local market and pay a visit to Safrantat to enjoy their delights, especially the one flavored with saffron, and buy a block of the layered yaprak helvası, thinking about how food has been connecting people beyond time and culture.Cork of the Week: When working on the Byzantium Breeze menu, I was desperately looking for a dessert wine to pair with the prune and grape pudding chef Serdar Yıldız created. Of course it would be decorated with a thin shaving of gastris or yaprak helvası. My friend Levon Bağış from the Kavaklıdere Winery came to my rescue. He suggested Kavaklıdere Narince Tatlı-Sert 2001, made from the delicate Narince white grapes, a deep, nectar-like sweet wine, so ideal to end a Byzantine-inspired dinner. While sipping this sublime wine one can easily imagine Empress Zoe enjoying her share, overlooking the historic peninsula from the terrace of Divan Brasserie at the roof of Anamed. Other wines we selected for the menu were Kavaklıdere Misket 2014, Kocabağ Emir 2012 and Chamlica Papazkarası 2015, this last one was an inevitable choice as the name of the local indigenous grape translates as Noir of the Priest.