Muslims seek more in Obama’s ’way forward’

Bloomberg

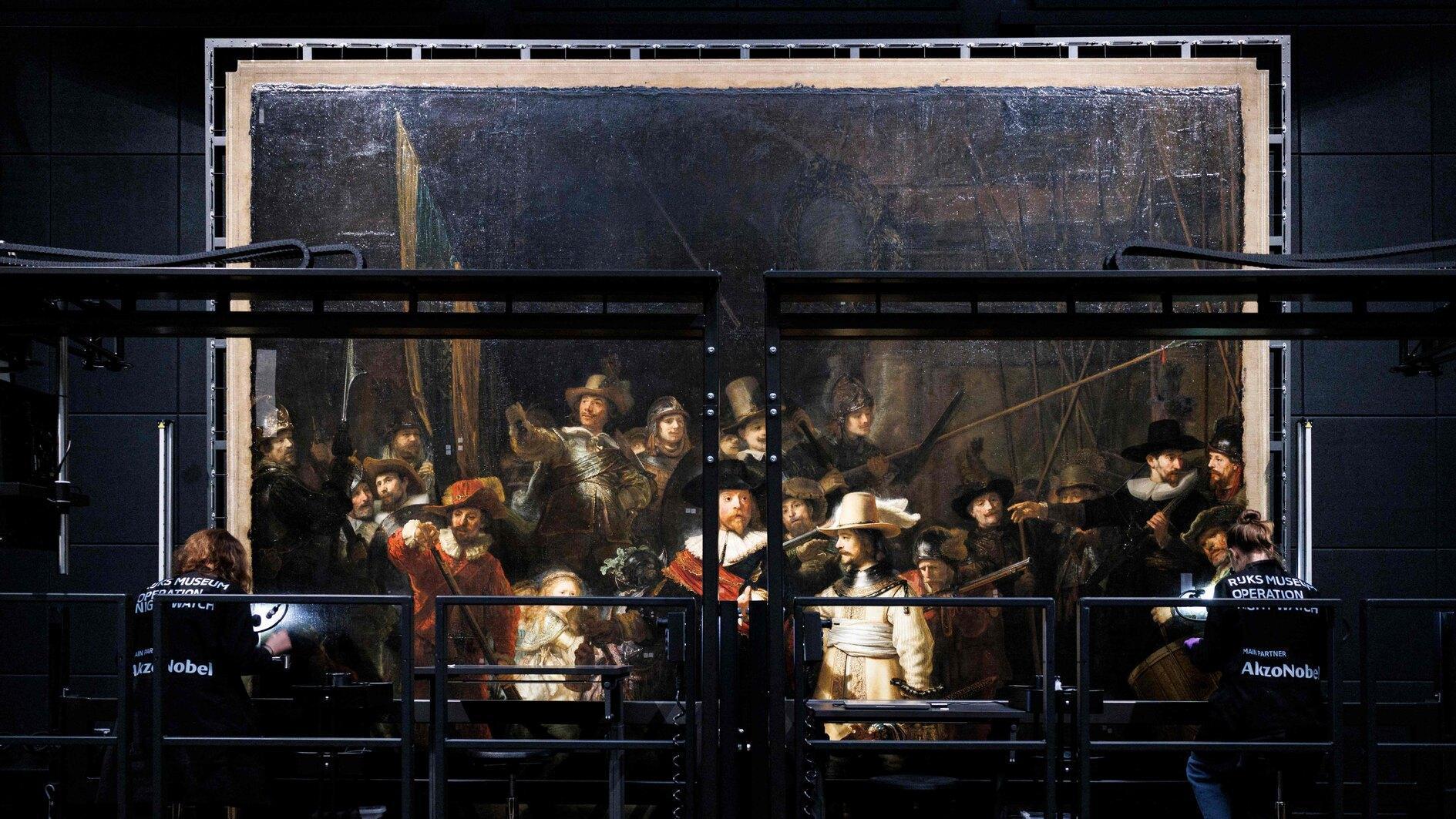

refid:11180927 ilişkili resim dosyası

Indonesia’s top-rated youth-music television show, featuring dancing divas in sequined mini-dresses, is an unlikely venue for President Barack Obama’s drive to repair the U.S. image among Muslims. Appearing on "Dahsyat", means Awesome, in Jakarta last month during her first overseas trip as secretary of state, Hillary Clinton was quickly reminded how tough that task may be. As she tried to connect with her audience in the most populous Muslim nation - talking about democracy and her love of the Beatles - she also was grilled on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict 5,400 miles (8,690 kilometers) away."Everyone is watching and waiting to see if this administration’s policy is really going to be friendlier to the Muslim world," said Yulia Supadmo, 38, a TV executive who listened as Clinton promised the U.S. "will get re-engaged" in Middle East peace.

Obama’s inaugural pledge to "seek a new way forward" with Muslim countries is much more than a popularity campaign. He needs help to solve shared problems related to energy security, Iran’s nuclear program and the terrorist threat from radical Islamists who have inspired many more attacks in Muslim nations than in the U.S. The global recession, which may threaten the political order in developing countries, may make his task more difficult.

Even in Indonesia, where a Gallup survey last year showed almost half the population had a favorable view of U.S. leadership - a far bigger share than in the Arab world - people want more than gestures from the new administration. America "is not going to get that cooperation if it’s seen as an imperial power, untrustworthy or working contrary to interests of Muslims," said Stephen Grand, who organized the U.S.-Islamic World Forum in Doha, Qatar, last month, where he saw cautious optimism among leaders from 35 countries who had largely tuned out President George W. Bush.

Reaching out to a complex and diverse constituency of 1.3 billion people in 57 nations in Africa, the Middle East and Asia can’t be a one-size-fits-all project. The first step is restoring respect, said Husain Haqqani, Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington. Bush "erroneously gave the impression that the ’war on terror’ was a reflection of U.S. hostility to Islam," he said. Obama must adopt "a much more nuanced approach, not the ’you’re with us or you’re against us’ that draws a circle and doesn’t allow anyone in," said Suhail Khan, a Muslim-American who served in the Bush White House. Among the issues facing the new president is whether to negotiate with the political wings of Hamas and Hezbollah, militant Islamic groups that don’t recognize Israel’s right to exist, and moderate elements of the Taliban.

Lowest approval

In the Middle East and North Africa, where median approval of U.S. leadership languished at 15 percent last year - the lowest in any region, according to Gallup - people surveyed said pulling out of Iraq, closing the prison camp at Guantanamo Bay and giving more humanitarian aid would "significantly improve" opinions about the U.S. One-third of the people interviewed in six Arab countries last year believed that "weakening the Muslim world" was a leading driver of U.S. foreign policy, according to Shibley Telhami, who surveys Arab political views as the Anwar Sadat Professor at the University of Maryland.

Half the people Telhami polled said attitudes would shift if the U.S. brokered a two-state solution for the Palestinians and Israel. "The key to the heart of the region is always what we do on the Arab-Israeli question," he said.

The Obama administration must also be mindful of the divide between the elite and the "street." In Egypt, where President Hosni Mubarak has benefited from more than $50 billion in American aid in his 28 years in power, public approval of the U.S. last year was 6 percent, Gallup showed.

Kazi Ahmad, a political consultant in Southeast Asia, said people want to see that "the U.S. is not just supporting authoritarian regimes in the Mideast, that there are strong partners for the U.S. in democratic Indonesia and Turkey." The global crisis and plunging crude-oil prices may open a door for economic diplomacy. Navtej Dhillon, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, said U.S. should seize the moment to push Middle Eastern countries for "institutional reform" in areas such as social protection for workers and access to affordable housing.