Multinational taxing under G20’s scope

LONDON / MOSCOW - Reuters

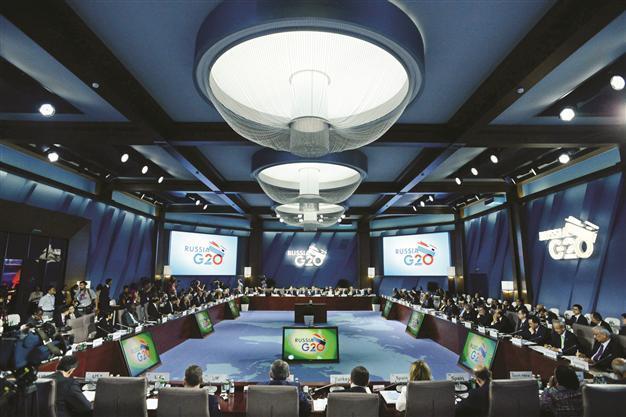

The G20 takes at loopholes used by multinational companies to avoid taxes. AFP photo

The G20 backed a “fundamental” rethink of the rules on taxing multinational corporations last week, taking aim at loopholes used by companies such as Apple and Google to avoid billions of dollars in taxes.The group of leading economies released an action plan drawn up by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that said the existing system didn’t work, especially when it came to taxing companies that trade online.

“It is a major breakthrough and is at the heart of the social contract,” France’s finance minister, Pierre Moscovici, told a news conference on the sidelines of a meeting of finance ministers from the Group of 20 leading nations in Moscow.

“People and companies have to pay the taxes that are due. It’s the only way to operate in a fair and competitive society,” added British finance minister George Osborne.

Large budget deficits and public anger at inter-company structures designed to channel profits into tax havens have prodded governments to act.

Google, Apple and others say they follow the law wherever they operate and pay what tax is due but also have a duty to shareholders to organise their affairs in a tax-efficient way.

Mark Nebergall, President of the Software Finance & Tax Executives Council, which represents companies including tech giant Microsoft, dismissed the accusations of profit shifting often levelled against his industry and warned there was a risk any OECD action would fall foul of “the law of unintended consequences”.

But Pascal Saint-Amans, Director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy, said the existing rules, which date back to the League of Nations in the 1930s, had led to a “golden era” of tax avoidance.

He said governments’ frustration with companies’ aggressive tax avoidance provided a “once in a century” opportunity for action.

The OECD, which advises its mainly rich members on tax and economic policy, has two years to come up with specific measures that can be adopted internationally. The OECD identified a raft of loopholes widely used by companies in the technology, pharmaceutical and consumer goods sectors, and Saint-Amans said the success of the project could be measured by whether there is a rise in the effective tax rates businesses pay.