For decades, Egyptians have dreamed of bringing back some of the glories of their ancient civilization scattered across museums and private collections across the world. Now as Cairo gears up to open “the largest archaeological museum in the world” at the foot of the pyramids of Giza in November, Egypt’s former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass told AFP that he will soon demand the return of three of its greatest lost treasures.

The basalt slab dating from 196 B.C. was the key that helped French linguist Jean-Francois Champollion crack the code of Egypt’s ancient hieroglyphs.

The stone was discovered by Napoleon Bonaparte’s invading French army in 1799 while troops were repairing a fort near the Nile Delta port of Rashid (or Rosetta), close to the Mediterranean.

It bore extracts of a decree written in Ancient Greek, an ancient Egyptian vernacular script called Demotic and hieroglyphics.

Comparing the three scripts finally helped resolve a mystery which had bedeviled historians for centuries.

Champollion announced his discovery on Sept. 27, 1822.

The stele has been housed in the British Museum since 1802, inscribed with the legend “Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801” on one side and “presented by King George III” to the museum on the other.

Egypt has been demanding its return for decades, with Egyptologist Heba Abdel Gawad saying the inscriptions alone were “an act of violence that no one talks about, and which the British Museum denies is destruction of an artefact.”

The museum told AFP that the stone was “handed over to the British as a diplomatic gift.”

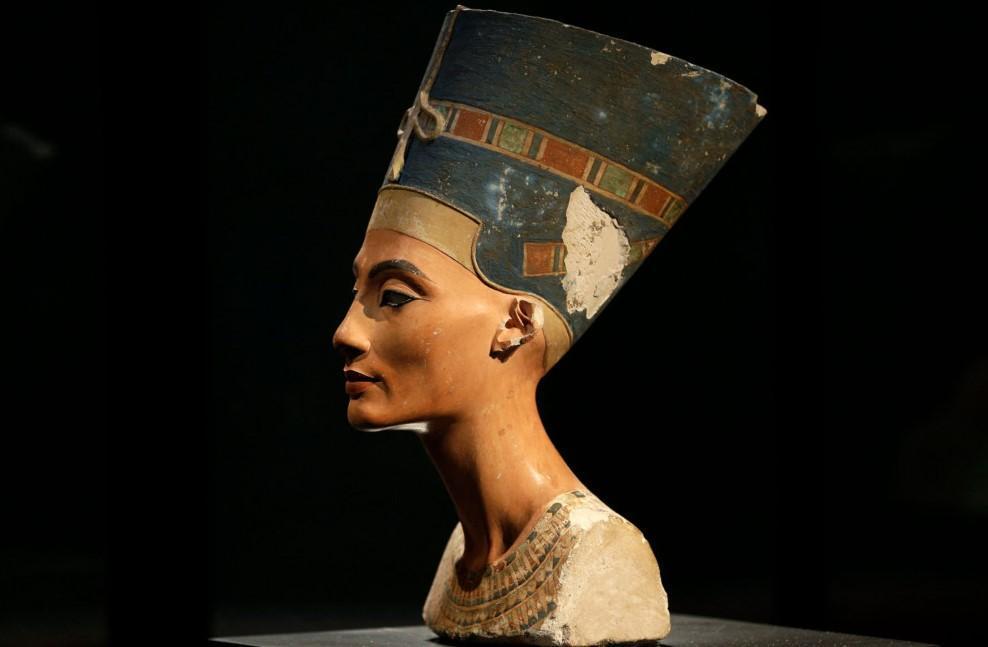

The bust of the wife of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, whose name meant “the beautiful one has come,” was sculpted around 1340 B.C. but was carted off to Germany in controversial circumstances by a Prussian archaeologist after it was found at Amarna in 1912.

The depiction of one of the most famous women of the ancient world was later given to the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Cairo demanded its restitution as early as the 1930s, but Germany has long held that it was handed over in a colonial-era partage agreement, under which countries that funded archaeological digs could keep half of the finds.

But for Hawass it “was illegally taken.”

Egyptologist Monica Hanna told AFP that Germany once agreed to give the bust back only for Adolf Hitler to block it after the Nazi leader fell under its spell.

No official requests for the treasures’ return have been received “from the Egyptian government,” according to the three European museums.

The celestial map was blasted out of the Hathor Temple in Qena in southern Egypt on the orders of French official Sebastien Louis Saulnier in 1820.

It has been suspended on a ceiling in the Louvre Museum in Paris since 1922, while a plaster cast stands in its place in the temple.

The chart, regarded as “the only complete map that we have of an ancient sky,” is thought to date from around 50 B.C.