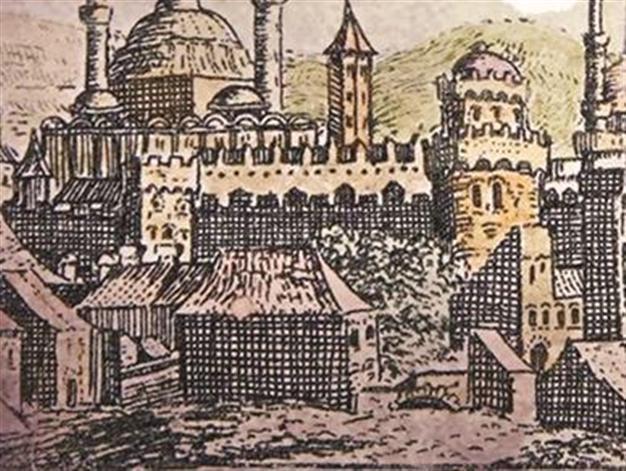

Lady Mary Wortley Montague's Edirne in 1717

Niki GAMM Hürriyet Daily News

Lady Mary was the first western European woman to write letters describing her journey to the Ottoman Empire, detailing her observations and experiences

in Edirne, where the court of Sultan Ahmed III was stationed.

“I am at this present moment writing in a house situated on the banks of the Hebrus [today’s Maritsa River], which runs under my chamber window. My garden is full of all cypress trees, upon the branches of which several couple of true turtles are saying soft things to one another from morning till night. How naturally do boughs and vows come into my mind, at this minute? And must not you confess, to my praise, that ‘tis more than an ordinary discretion that can resist the wicked suggestions of poetry, in a place where truth, for once, furnishes all the ideas of pastoral. The summer is already far advanced in this part of the world…”

And so Lady Mary Wortley Montague began one of the famous letters she wrote on April 1, 1717, just after her and her husband, the British ambassador Sir Edward Wortley Montague, arrived in Edirne. She was the first western European woman to write letters describing her journey to the Ottoman Empire, detailing her observations and experiences in Edirne where the court of Sultan Ahmed III was stationed at the time and later in Istanbul. She was clearly impressed with what she saw and took great pleasure in depicting it.

Lady Mary describes the Edirne countryside in much the same terms that the 17th century traveler Evliya Celebi wrote of Sadabad in Istanbul.

“For some miles round Adrianople, the whole ground is laid out in gardens, and the banks of the rivers are set with rows of fruit-trees, under which all the most considerable Turks divert themselves every evening, not with walking, that is not one of their pleasures; but a set party of them chuse [sic.] out a green spot, where the shade is very thick, and, there they spread a carpet, on which they sit drinking their coffee, and are generally attended by some slave with a fine voice, or that plays on some instrument. Every twenty paces you may see one of these little companies listening to the dashing of the river; and this taste is so universal, that the very gardeners are not without it. I have often seen them and their children sitting on the banks of the river, and playing on a rural instrument, perfectly answering the description of the ancient fistula, being composed of unequal reeds, with a simple, but agreeable softness in the sound.”

Third capital of OttomanEdirne was the third capital of the Ottoman Empire after Iznik and Bursa and was even preferred by Fatih Mehmet I after he conquered Constantinople. Sultans Mehmed IV and Mustafa left Istanbul completely for Edirne during their reigns and it is not surprising that Ahmed III also preferred the latter city. Lady Mary, who praised the city’s location and the countryside around it, however, didn’t hesitate to proclaim the air extremely bad, even at the palace, which was some distance away. The river Maritza, she says, was very pleasant and had two bridges built over it but in summer it dried up.

There were public gardens that have köşks that served coffee, sherbet and other drinks. The mosques were made of stone and, according to Lady Mary the hans were magnificent, designed around a large square with cloisters around a courtyard.

Lady Mary and her husband stayed in a palace that belonged to the sultan. She notes that these kinds of houses were built of wood and not particularly beautiful on the outside. She claims that because every house reverts to the sultan upon the death of the “owner” they don’t see much reason to spruce them up on the outside. It’s the painting and furnishings on the inside that are very impressive, for instance, Persian carpets and silk coverings.

“The rooms are all spread with Persian carpets, and raised at one end of them (my chambers are raised at both ends) about two feet. This is the sofa, which is laid with a richer sort of carpet, and all round it a sort of couch, raised half a foot, covered with rich silk, according to the fancy or magnificence of the owner. Mine is of scarlet cloth, with a gold fringe; round about this are placed, standing against the wall, two rows of cushions, the first very large, and the next, little ones; and here the Turks display their greatest magnificence. They are generally brocade, or embroidery of gold wire upon white sattin [sic.]. —— Nothing can look more gay and splendid. These seats are also so convenient and easy, that I believe I shall never endure chairs as long as I live,” she wrote in one of her letters.

“But what pleases me best, is the fashion of having marble fountains in the lower part of the room, which throw up several spouts of water, giving, at the same time, an agreeable coolness, and a pleasant dashing sound, falling from one basin to another. Some of these are very magnificent.”

Lady Mary was also much taken with the gardens inside the women’s sections that were enclosed with high walls. The tall trees provided shade and in the center, there would be a small köşk covered with vines, jessamine and honeysuckle, with a fountain in the middle of it. It was the perfect place to sit playing music or engaging in embroidery. Thanks to a great sense of curiosity, Lady Mary hired a Turkish coach in order to get around Edirne. That way she wasn’t identified so readily as a stranger. They had wooden lattices painted with flowers intermixed with poetic mottos. Although they were covered with scarlet cloth, this covering could be drawn back to allow the women to see through the lattices. On one occasion she went with the French ambassadress to see the sultan going to the mosque and she describes the various people in the procession and what they were wearing.

“Last came his sublimity himself, arrayed in green, lined with the fur of a black Moscovite fox, which is supposed worth a thousand pounds sterling, and mounted on a fine horse, with furniture embroidered with jewels. Six more horses richly caparisoned were led after him… The sultan appeared to us a handsome man of about forty, with something, however, severe in his countenance, and his eyes very full and black. He happened to stop under the window where he stood, and (I suppose being told who we were) looked upon us very attentively, so that we had full leisure to consider him,” she later wrote of the experience.

On top of everything, Lady Mary passed along gossip, not just about other foreigners but about some of the prominent Turks. For example, she describes the aftermath of Sultan Ahmed III’s eldest daughter’s wedding. The widowed Fatma Sultan is just 13 when she’s married off to İbrahim Paşa.

“When she saw this second husband, who is at least fifty, she could not forbear bursting into tears. He is indeed a man of merit, and the declared favourite of the sultan, (which they call mosayp) but that is not enough to make him pleasing in the eyes of a girl of thirteen,” she wrote.

How fortunate we are to have glimpses of life in Edirne in 1717 from the Montague letters.