'Küf' gets global recognition, but not so much at home

Emrah GÜLER

Ali Aydın’s debut feature ‘Mold’ won the Lion of the Future Award at the Venice Film Festival last

summer.

The 31-year-old director and writer Ali Aydın’s debut feature “Küf” (Mold) was a source of pride for followers of Turkish cinema last year. The film won the Lion of the Future Award at the Venice Film Festival, the prize given to the best first work, last summer. The Lion would be the first of many awards “Küf” would go on to win here and abroad.

The film was part of a selection by New York’s Museum of Modern Arts (MoMA), screening the works of newcomers across the globe. New Directors/New Films was a collaborative effort by MoMa and the Film Society of Lincoln Center. At around the same time, “Küf” impressed, among others, one of the prominent names of independent cinema, Rob Nilsson, at the Los Angeles Turkish Film Festival, reminding him of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy.

One month later, the copies of “Küf” traveled to its original source of pride, going on to national release in Italy. While the film was screened in 12 cities, from Rome to Torino and Bari with 15 copies, raving reviews adorned the Italian media. The film is slated also for a release in Greece, where it won the Silver Alexander award at Thessaloniki Film Festival last November.

This picture of global acclaim that was making every Turkish film aficionado proud and happy came to an abrupt sad ending last Friday, when it was finally supposed to be released in theaters in its home country. Those expecting to see this classic-in-the-making last weekend met with a chilling announcement on the film’s official Facebook page: “The release date of ‘Küf,’ that was supposed to be today, is postponed due to problems in finding a theater to screen the film.”

Festival films vs. popcorn entertainmentIt’s become a recurring theme for the so-called art movies that are making the rounds in the international festival circuit to find theaters that are willing to screen them to a handful of viwers, as opposed to Hollywood blockbusters and Turkish comedies that are guaranteed to draw crowds to theaters.

Last December, film lovers, festival followers and filmmakers were furious when Emin Alper’s “Tepenin Ardı” (Beyond the Hill), the winner of 16 awards, including the Caligari and Best First Feature Film Special Mention in Berlin International Film Festival, was able to secure only seven movie theaters for its release.

In an interview with the daily Hürriyet last March, Aydın had mentioned his awards and the upcoming screenings around the world, ending the interview with a premonition: “The film is slated for release in Greece, France and Italy. However, we are having problems in finding theaters for its release in Turkey. The monopolization in theaters is becoming a serious problem.”

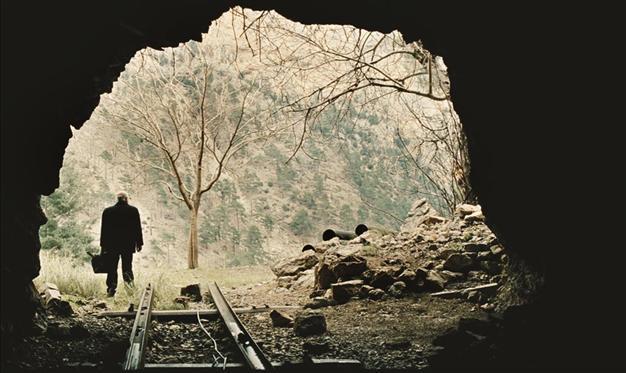

“Küf” is not the easiest film for moviegoers that are accustomed to popcorn entertainment hoping for some distraction for a couple of hours in the air-conditioned movie theaters. It is a deep, and often times painful, study of one of the loneliest characters to come to Turkish cinema. The character is Ercan Kesal’s Basri, a railroad inspector, a job that confines him to even more solitude after having his son “disappear” under custody 18 years ago and becoming a widower soon after.

A touching story of lossThe only sense of purpose Basri has is the peititons he is being sending to the authorities to find his son for the last 18 years. The long sequences and minimal dialogue give the audience a feeling of watching a nature documentary, of a creature that has a painfully slow existence and deep-rooted solitude. The feeling is also of hopelessness, knowing that there is no happy ending in the conventional sense for this creature.

Kesal’s unassuming acting at once drives the audience to an urgent desire to connect with this heartbroken man and to run as far away as possible. The supporting characters, like Basri’s co-worker and the police, and carefully planted details, like the date of a death corresponding to the same date of the fallen journalist Hrant Dink, make watching “Küf” an even more harrowing experience.

One of the last names is on a tombstone is Aydın, same with the director’s, of which he said, “I, especially, put my name on the tombstone. We are all human before our political alliances and choices. However, none of us are protected by the law. We can all disappear under this vicious circle.”

Responding to a question about the choice of the film’s title, “Mold,” Aydın said, “I wanted to tell a specific period in Turkey’s recent history, the 1990s; a decaying, rotten period. The name of the film takes after this decay.” Despite its heavy subject matter, the film refuses to be an angry political drama, and becomes more a touching story of loss. As one audience said after the film’s screening in last year’s Festival on Wheels, “You have made a universal film about this country’s wounds, not focusing on a specific region or a specific problem. Loss is a universal pain.” It might be a loss for the Turkish audience if the film isn’t able to secure a theater in the future.