Gulf rivalry between Iran, UAE transfered to the football pitch

James M. Dorsey

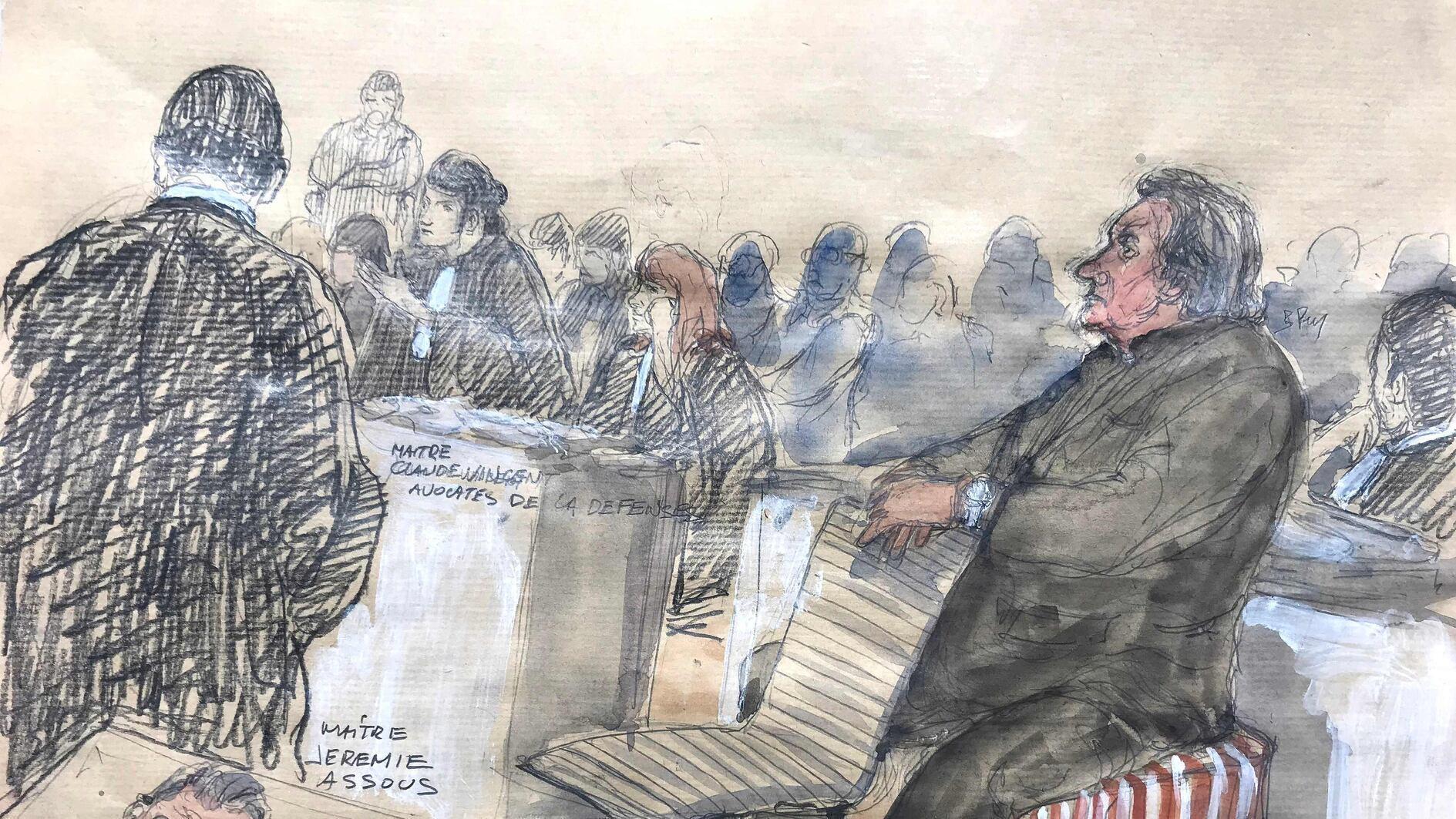

Iranian national team captain Javad Nekounam (2R) is at the center of a transter controversy between his country and the United Arab Emirates. The midfielder’s $2 million transfer to Al-Sharjah was halted by the Iranian Football Federation in a decision apparently led by political conflicts between Iran and the UAE. REUTERS photo

The battle between Iran and various Gulf states for the identity of the energy-rich region has spilled onto its football pitches. It’s the Persian Gulf League vs. the Arabian Gulf League.The struggle erupted when the United Arab Emirates, alongside Saudi Arabia, the Gulf’s most fervent opponent of political Islam, recently renamed its premier league as the Arabian Gulf League. The Iranian football federation, whose own top league, the Persian Gulf League, adheres to the Islamic republic’s position in the war of semantics, responded by blocking the transfer of Iranian players to U.A.E. clubs and breaking the contracts of those who had already moved.

The war has stopped Iran’s national team captain Javad Nekounam from being sold for $2 million to U.A.E. club Al-Sharjah. “We had to stop him from joining the Emirati league. We will ask the president (Mahmoud Ahmadinejad) to allocate” funds to compensate Nekounam for his loss, said Iranian football federation head Ali Kafashian. Quoted by Fars news agency, Kafashian said another eight or nine players had also been prevented from moving to the U.A.E.

“The Persian Gulf will always be the Persian Gulf. Money is worthless in comparison to the name of my motherland. I received an offer from Al-Sharjah three months ago and no one forced me to deny it, but I refused to do so myself. I would never join a team from a league offending the name of the Persian Gulf,” Nekounam said on Iranian state television.

Strained relations

The Iranian federation, which has long been micro-managed from behind the scenes by Ahmadinejad, made its move three weeks before the president steps down and is succeeded by President-elect Hassan Rouhani, a centrist politician and cleric who many hope will seek to improve strained relations with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states.

The kingdom, the U.A.E. and Bahrain have accused Iran of interfering in their domestic affairs by fueling Shiite anti-government protests. They are also at loggerheads over Syria with Iran-backing embattled President Bashar al-Assad and the Gulf states supporting rebels opposed to him. The animosity has fueled a widening sectarian gap in the region between Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

The U.A.E. moreover has its own gripes against Iran because of the Islamic republic’s four-decade-old occupation of three potentially oil-rich islands claimed by the Emirates that are located near key shipping routes at the entrance to the Strait of Hormuz. The U.A.E. last year declared a boycott of Iranian players that it did not implement in a bid to pressure Iran to return the islands and put its controversial nuclear program under international supervision.

A year earlier, the U.A.E. became with remarks made by its ambassador to the United States, Yousef al-Otaiba, the first Gulf state to publicly endorse military force to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear power.

The U.A.E. has in recent years further worked to link its security more closely to U.S. and European security interests. France inaugurated in Abu Dhabi its first military base in the region. The base, which comprises three sites on the banks of the Strait of Hormuz, houses a naval and air base as well as a training camp, and is home to 500 French troops. Alongside other smaller Gulf states, the U.A.E. has further agreed to the deployment of U.S. anti-missile batteries on its territory.

U.A.E. clubs signaled this week that they would comply with the Iranian boycott in a move that strengthens Emirati resistance to Iranian policies. “We don’t want to be drawn into a political warfare and if it is true, the club management will take necessary action to avoid any confrontations,” said an official of the Sharjah club that had been negotiating with Nekounam. Kafashian said it was negotiating with Ajman to break the contract of Iran’s Mohammed Reza Khalatbari, who had transferred before the Iranian football federation declared its decision to bar Iranian players from moving to the U.A.E.

NAMING A GULF ‘TURKISH STYLE’

ISTANBULThe common practice in Turkish may be the way out of the dispute over how to name the gulf surrounded by Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Gulf states.

The gulf in question, Persian Gulf for many while the Arabian Gulf to others, is called the “Basra Gulf” in Turkish, as gulfs are named after the city or town that surrounds the end of the bay. For example, the gulf located in the northeastern Mediterranean is named the Gulf of İskenderun, after the town located at the end of it. A similar practice can also be observed in the names of other gulfs, including the Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Bahrain and Gulf of Odessa.

Such a method of naming limits the debate over the names of gulfs to geographical means, helping to avoid political and regional fights over a body of water.

Or all parties could continue debating whether it is the “Islamic Gulf” or the “Arabo-Persian Gulf.”