From Central Asia to the Byerley Turk

Hürriyet Daily News

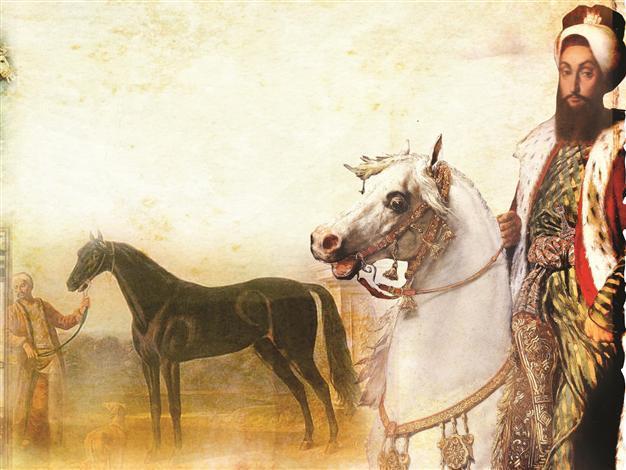

The main evidence for what kind of horse the Ottomans rode is to be found in many miniature paintings produced over the centuries, in which the horses had small heads whether they were in the midst of a battle or on parade.

The Byerley Turk was the one of three stallions brought to Britain around the beginning of the 18th century. The three’s descendants became known as thoroughbreds and are among the horses that even today compete in races at Istanbul’s Veliefendi Race Track.An English army officer, Captain Robert Byerley obtained his horse, probably as a prize of war from an Ottoman officer following the Battle of Buda (1686) when the town was captured. A dark brown horse, he had large eyes, an arched neck and upstanding tail – all characteristics of Arabian horses. Some believe he was Arabian; others don’t think so. One expert has even questioned paintings which show the horse with a very small head. How could a horse have such a small head? Where did the horse come from?

Until the invention of the automobile, people used horses, camels, mules and the like to get around. No one knows when the horse was domesticated although some discoveries in suggest it was 3-4,000 years ago in Central Asia, where they provided milk and meat in addition to being ridden and carrying loads. Recent evidence shows that horses originated in North America and migrated across the Bering Strait while it was still connected with Asia.

Value of the horse was well-recognized

Early cave dwellers painted horses on walls, and these representations had small heads. Myths in the Middle East indicate that the value of the horse was well recognized, just as burying horses with their owners in Central Asia and Central Europe shows how close the relationship had become. The legends of the Turks tell of the importance the horse had for the nomads and warriors of the steppes in their travels and battles. In their paintings of horses, the Göktürks of Central Asia (552-744 A.D.) showed them with small heads.

But heads didn’t actually matter as much as what the horse would be used for, and that was how they were bred. Speed, strength, calmness and intelligence were among the attributes required at various times.

The origin of the Arabian horse is unknown although distinguished by its head shape, tail, intelligence, speed and endurance. They may have come from the Fertile Crescent to the Bedouin of the Arabian Desert where they were particularly liked for their usefulness in raiding and warfare. Certainly the first written records concerning the Arabian horses date from 1300 AD Egypt but by that time they had been spread throughout North Africa as far as Spain and in the Middle East as far as India.

Original Turcoman horse left its mark

The original Turcoman horse has become extinct; however, it left its mark on later breeds such as the Akhal-Teke and Yamud. The Turks would have ridden the Turcoman which they bred to suit the conditions of Central Asia and their frequent engagement in raiding and warfare. As such, the Turcoman had swiftness and stamina, fine coats, long backs and small hooves to deal with the sand of the Central Asian deserts. Noticeably more slender than the Arabian, the Turcoman is sometimes described as having been the greyhound among the horse breeds. Its slenderness gave an archer on its back the advantage of being able to turn and twist more easily in spite of his mount being a very tall horse, taller than the Arabian. Both the Turk of Central Asia and the Bedouin of the Arabian Peninsula lived closely with their horses and took care of them as if they were members of their families.

The Turcoman and the Arabian probably were first introduced to each other during the Mamluke era in Egypt. The Mamlukes were slaves from Turkish tribes who rose to power through their military ability, for the most part in various centers of the Middle East and especially in Egypt (1250–1517). They are known for having brought horses from the Caucasus area in particular, but were less interested in breeding than in show.

The horses of the Byzantines were varied depending on the purpose they would be put to, such as chariot racing. A number of different breeds entered the Byzantine Empire as a result of hiring mercenaries to ward off their enemies, and these included archers on horseback. The imperial cavalry on the other hand wore armor and rode larger, stronger horses that contrasted significantly with lighter clad, more mobile Turkish archers.

The main evidence for what kind of horse the Ottoman Turks rode is to be found in the many miniature paintings produced over the centuries, in which the horses had small heads whether they were in the midst of a battle or on parade. Some of these depictions stem from the fact that the artists used patterns to draw horses, although it doesn’t account for the small heads.

That may have been because the horses used by the Turks had slender, refined heads such as the Byerley Turk had. It wasn’t until Western European artists arrived on the scene in the 19th century that better proportioned depictions became the norm.