Football deaths raise stakes for Egyptian President el-Sisi

James M. Dorsey

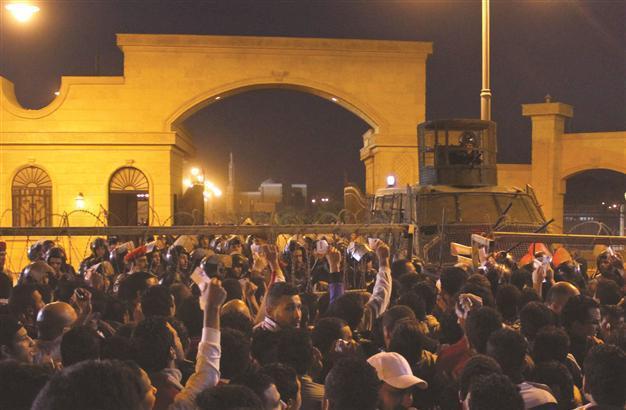

Football fans argue with security personnel as they attempt to enter a stadium, before a scuffle broke out, on the outskirts of Cairo. REUTERS Photo.

A recent stampede in which at least 19 Egyptian football ultras due to the actions of security forces suggests that the government of General-turned-President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has no intention of easing its crackdown on political dissent.

The incident, the worst in Egyptian sporting history after the death of 74 fans in a politically loaded brawl three years ago in the Suez Canal city of Port Said, nonetheless raises the stakes for the government because it involves groups that project themselves as non-political but have proven themselves in years of clashes with security forces, primarily in Egyptian stadia.

The death of the fans in Cairo moreover dealt a lethal blow to government efforts to weaken the militant fans or ultras by partially lifting in early February a ban on spectator attendance of football matches imposed since Premier League matches suspended after the Port Said brawl were allowed to resume.

The government’s immediate blaming of the Ultras White Knights (UWK), the militant support group of storied Cairo club Zamalek SC, suggests that it may use the incident to push ahead with efforts to outlaw the ultras, who played a key role in the 2011 popular revolt that toppled President Hosni Mubarak as well as protests against subsequent military rule, the elected government of Mohamed Morsi that was overthrown by a military coup in 2013, and the el-Sisi government.

Egyptian media have in the last 18 months repeatedly sought to portray the ultras as violent thugs who were being funded by unidentified political forces, a reference to Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood that was outlawed in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates after the coup.

Mansour’s efforts similar to trial of çArşı in TurkeyZamalek President Mortada Mansour, a colorful, larger-than-life character and controversial fixture of the Mubarak era who withdrew his presidential candidacy in elections in 2014 to allow el-Sisi to run unopposed, has tried to persuade the courts – unsuccessfully so far – to ban UWK as a terrorist organization. Mansour’s efforts are part of a broader endeavor to criminalize protest similar to developments in Turkey where 35 members of Beşiktaş’s çArşı group are standing trial for belong to an illegal organization and attempting to topple the government.

Two Egyptian courts recently rejected Mansour’s petition on the grounds that they were not competent. However, a third court sentenced 20 UKW members to several years in prison in January on charges of inciting violence, assaulting security forces and damaging private property. Mansour has also accused the UWK of trying to assassinate him. Denying the allegation that led to the arrest of scores of UWK members, the group has dubbed the Zamalek president “the regime’s dog.”

Mansour’s son, Amir Mortada Mansour, in line with the government’s blaming of UWK for the fans’ death, said in a tweet shortly after the stampede that has since been deleted that “football is only for respectable fans. No thugs are allowed here,” a reference to the Cairo stadium. Earlier, the Zamalek president’s son charged in an interview with The Los Angeles Review of Books that the UWK was a front for the brotherhood in a bid “to show the world that there is no stability in Egypt and to create problems for the current regime at universities and at stadiums.”

The stampede has refocused attention on stadia as a major flashpoint of opposition to successive Egyptian governments. It is certain to charge in coming weeks and months other potential football-related flashpoints including the legal efforts to outlaw the UWK as well as the pending appeal against the sentencing to death of 21 fans of Port Said’s al-Masri SC and lengthy prison sentences for others on charges that they were responsible for the brawl in the Suez Canal city.

The influence of the ultras as a potent opposition force has been evident in student protests in the past year in which football fans also played an important role. The ultras’ style of protest, including its chants and the jumping up and down was replicated by students, some of whom were members of Ultras Nahdawy (Renaissance Ultras), the only group of ultras that is not linked to a specific club and defines itself explicitly as political.

Nahdawy, whose name refers to the term used by the Brotherhood to describe its political and economic program, was formed by members of UWK and Ultras Ahlawy, the militant support group of Zamalek arch rival al-Ahly SC that was the target in the Port Said incident, asserted that it has distanced itself from the brotherhood since the group was outlawed.

Taken together, the battles of the students in universities and fans in stadia is one for public space and against efforts by el-Sisi to depoliticize youth emboldened by its success in overthrowing Mubarak and angered by their being sidelined in the wake of their successful revolt and the rolling back of heavily fought achievements.

A lack of public space under Mubarak, who, like el-Sisi, tolerated no uncontrolled public space, propelled the fans to the forefront of anti-government protest. History threatens to repeat itself under el-Sisi despite the fact that he acknowledges that he and his predecessors have failed to reach out to youth under the age of 25 who account for half of the Egyptian population.

Youth disaffection was evident in the absence of young voters in a referendum under post-Morsi military-backed rule and last year’s presidential election that brought el-Sisi to office.