Fans hope Froome may boost sport in Kenya

KIKUYU, Kenya - Reuters

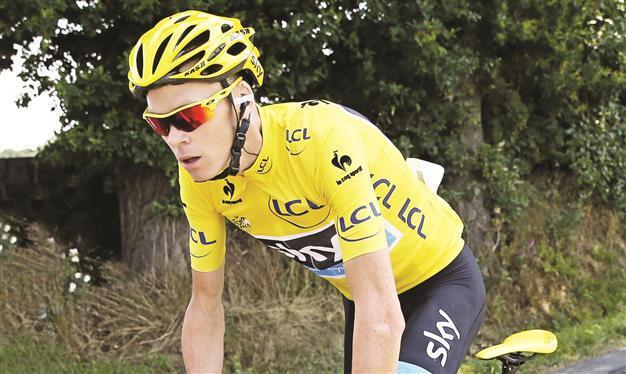

Overall leader’s yellow jersey Britain’s Chris Froome rides during the tenth stage of the 100th edition of the Tour de France. Kenya-born British cyclist’s possible victory could start a new generation of cyclists in the African country. AFP photo

As Chris Froome races up France’s snow-capped mountains in a series of lung-busting Tour de France climbs, one man in a far away Kenyan village hopes a win for the “thin boy” he introduced to road cycling can transform the sport’s popularity in Kenya.

“Chris is our big hope now,” said David Kinjah, Froome’s former mentor, as he watched television images showing the Kenyan-born rider nearing the end of stage eight of the Tour.

In the east African country best known for its champion runners, cycling has faced an uphill struggle to compete with athletics and soccer, sports which are not only more popular but also much more affordable.

“If you play football, it’s easy - one ball for 20 people,” explained 41-year-old Kinjah, as 10 young riders crammed his modest corrugated-roof home, which is filled with cycling medals, trophies and spare bike tyres.

“We have limited access to funds and bicycles here so if you put more boys on the bikes, you have to take care of them,” said Kinjah, who also does cycling tours for tourists.

Froome survived a brutal early onslaught from his Tour de France rivals on Sunday to retain the yellow jersey after an epic ninth stage won by Ireland’s Dan Martin.

Some of the challenges faced by the Kinjah’s Safari Simbaz team, made up of teenage boys and young men from nearby villages, also frustrated young Froome when his single-parent mother introduced him to Kinjah.

Froome had to borrow a road bike from a sympathetic teacher as his mother, living in the servant quarters of a wealthy family in a Nairobi suburb, could not afford a new one.

“The teacher said ‘you can have it’, but it was a huge bike with a large frame so Chris couldn’t properly reach the pedals or the handle,” Kinjah remembered, laughing and shaking his head.

‘Role model’ Froome, 28, fell in love with cycling in Kinjah’s Mai-I-Hii village, reachable only by a sunkissed dirt road piercing through the lush green hills of Kikuyu, north of Nairobi.

In media interviews, the Olympic bronze medalist has described Kinjah as a “role model” and an inspiration.

“He helped me see you didn’t need the best bike or perfect conditions. You can just get on a bike and go - no matter where you are,” Froome told Britain’s Guardian newspaper in January.

Kinjah, who remains Kenya’s top cyclist, said Froome was a shy but determined boy, cared for by a mother who did her best to find an outlet for her son’s energy.

“He became one of us. We were happy, we didn’t care about tomorrow. We moved one day at a time,” said Kinjah, who cycling enthusiasts in Africa recognise by his flowing dreadlocks.

Eating plain white bread and bananas with sweet chai (tea), Kinjah said he had no idea the 12-year-old Froome would become a future champion, although he did recognise a steely determination.

“He was a very thin boy, nothing special,” Kinjah said. “But he was not the kind of guy you could tell ‘this is enough, stop it’. He always wanted to go further. He wanted to discover his own world.”

A few years later, Froome moved to South Africa to study, but kept coming back during school breaks to Mai-I-Hii to ride across the highlands with Kinjah’s Simbaz.

‘Nothing special’As Froome crossed the stage eight finish line on Saturday, the young riders in Kinjah’s house jumped up and cheered, aware that someone who spent years in the same room had just won the yellow jersey in the world’s most prestigious road race.

“This makes me really motivated. I want to get there,” said Vincent Chege, 18, who is one of around 20 boys who ride as Safari Simbaz, which means Safari Lions in Kiswahili. Some of the younger Lions watched the race with their helmets on.

“I just keep telling these boys ‘look at Chris Froome’,” Kinjah said. Though with no money and no support from parents, he concedes Kenyan riders stand little chance of making it.

Kinjah said Froome, who won a medal for Kenya in the All Africa Games in 2007, was right to switch his allegiance to Britain in 2008, even though it was a big loss for his country.

“He should have been a Kenyan,” said Kinjah, who was nicknamed Black Lion during his stint in Italy riding for a professional cycling team in 2002. “But Chris had zero support from the Kenya Cycling Federation.”

Kinjah said that for the 2006 Road World Championships Froome used official federation e-mails to enter himself, without the knowledge of officials who did not support him.

After Kinjah obtained the password for the e-mail account, Froome wrote e-mails pretending to be the chairman and entered himself for the tournament. But the move didn’t go to plan as Froome crashed into an official.

“I still have a photo of that crash: it says ‘White Lion Knocking Down The Prey’,” Kinjah said, chuckling.

Kinjah and Froome have stayed close, even though Froome’s family link to Kenya was severed when his mother passed away in 2008. Last month Froome sent his Team Sky kit for Kinjah to auction.

But Kinjah joked that Froome would not get the better of his one-time mentor even as Tour favourite. “He will never beat me, as I’m too old to race him now. He’s missed his chance.”