Eyüp Mosque, the Ottomans’ ‘coronation’ mosque

Niki Gamm

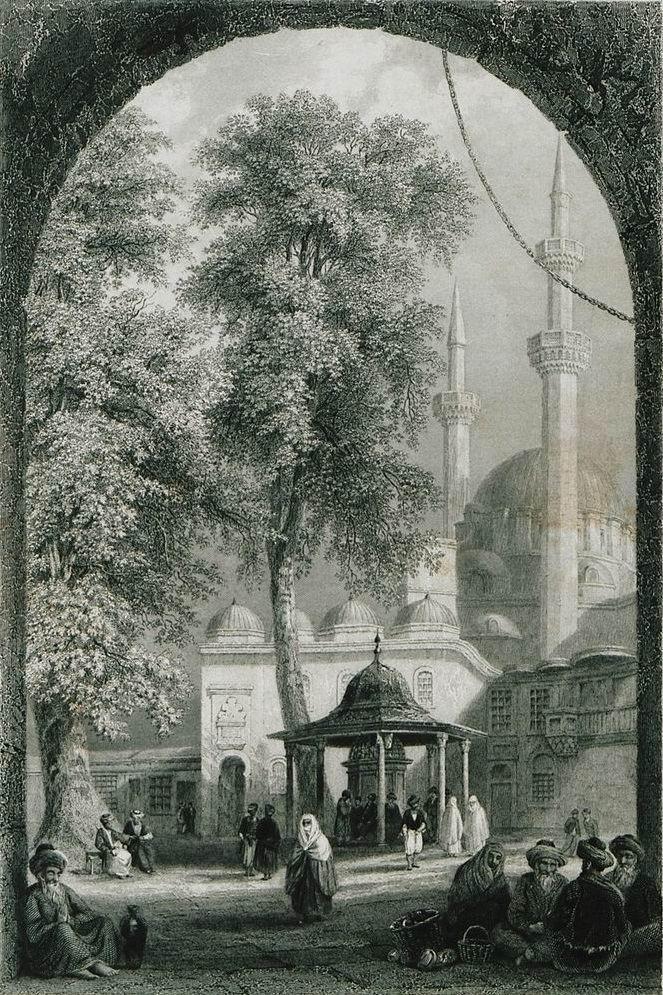

The sultan leaving Eyüp, 19th century. T. Allom.

Eyüp is a small village on the south, southwestern side of the Golden Horn outside the walls of Constantinople or the “Old City,” as it is sometimes known. Little information about its beginnings has survived until today and the first it was referenced is when Emperor Justinian built a church in the 6th century to two saints, Cosmas and Damian, who had been martyred by Roman Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305). The two saints were physicians who didn’t accept payment and were credited with grafting a black man’s leg onto a white man’s body. Although the church was destroyed somewhat later, a monastery was built there, consecrated to the same two saints. The place was considered sacred and people traveled there to be healed.

According to one Turkish source that doesn’t cite any original source, Byzantine emperors went there for their coronations. This seems at odds with the generally accepted knowledge that they were crowned in the St. Sophia Cathedral. The historian Robert Mantran wrote it was at this monastery to Saints Cosmas and Damian that the Byzantine emperor, his nobles and his generals used to don their swords and depart for war. The same Turkish source suggests that this is why the Ottoman who had become sultan would be girded with a sword in Eyüp following the conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

Eyüp al-Ansari’s final resting place

Eyüp al-Ansari’s final resting place

Shortly after the Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632, the Arabs began to expand throughout the Middle East, North Africa and into Anatolia. One of their most treasured dreams was to capture Constantinople and they tried to accomplish this, but to no avail. Among the leaders of the first expedition was Eyüp al-Ansari, the Prophet’s companion and standard bearer. He died in 672 or 674, either from old age or from one of the illnesses rampant among the soldiers of the besieging army and was buried near the walls of Constantinople. Assuming the legend concerning the finding of his grave is true, at least in part, a stone bearing an inscription in Arabic was placed over his body and then earth piled on top so that his grave couldn’t be discovered.

The legend has Fatih Sultan Mehmed wondering where Eyüp al-Ansari was buried. When no one could tell him and no one could find it, the sultan’s professor, Akşemseddin, has a dream in which he sees the exact location. The next morning he tells the sultan and they go and find the grave. While this makes a nice story, two Arab historians have written that the people of Constantinople were aware of where Eyüp al-Ansari was buried and often went there to pray for good health especially. This suggests there was a certain confusion, not provable, between the al-Ansari legend and that of St. Cosmas and Damian. On the other hand, historian Murat Belge has suggested that Fatih Sultan Mehmed may have been playing a trick in order to raise the morale of his troops.

Fatih Sultan Mehmed had a proper türbe (mausoleum) built over al-Ansari’s grave, a mosque and a complex of buildings next to it. But what we see today is not the original mosque. That was ruined by an earthquake in the 18th century, but at least its minarets were replaced by Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Paşa during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the mosque was restored on the order of Sultan Selim III. Today, the mosque, türbe and a portion of the complex’s hamam still remain.

A ‘coronation’ mosque

A ‘coronation’ mosqueThe al-Ansari türbe at Eyüp, and consequently the mosque too, became a site of religious pilgrimage that is considered to rank just after Mecca and Jerusalem. This designation seems to have been put to good use by the Ottoman sultans. While one thinks of coronations as involving great ceremony, prayers and crowns in majestic cathedrals, that was not the case among the Ottomans. Among them, whoever the heir was, once he was acknowledged, had his position cemented by being girded with the sword of Osman. This symbolized his martial ability to lead the Ottoman army and defend the empire.

This tradition stemmed from the earliest days in the rise of the Ottomans when they were still centered in Konya. Osman, who was successfully expanding Ottoman territory, had a close relationship with Şeyh Edebali, who was the head of the Mevlevi mystic sect whose headquarters were in Konya. In fact, the latter’s daughter was one of Osman’s wives. Şeyh Edebali is supposed to have girded Osman with a sword and encouraged him to go out and conquer the world.

The tradition must have been continued over the ensuing centuries to the point where it became necessary for each new sultan to be girded with Osman’s sword at the Eyüp mosque by the head of the Mevlevis in Konya within two weeks of his accession to the throne in order to be considered legitimate. The şeyh in charge of the Mevlevis had to be summoned to Istanbul. On the day of the ceremony, the sultan would travel from Topkapı Palace to Eyüp by boat or from Dolmabahçe Palace in the 19th century. No one has yet to come up with a theory why he would go by water – it took less time, was less dangerous, could be seen by more people from the shore, or Fatih Sultan Mehmed traveled that way. We likely won’t ever know.

The sultan would land at Eyüp and then on horseback slowly move up the street between rows of bowing nobles and saluting military and the graves of the wealthy – Eyüp was one of the fashionable places to be buried in Istanbul. At the entrance to the mosque, he would dismount and proceed to a small platform, over which towers an ancient plane tree in the mosque’s courtyard between al-Ansari’s türbe, and the mosque where he would be girded with Osman’s sword and possibly those of the Omar, the fourth caliph, and Yavuz Sultan Selim I. He would then proceed to enter the city on horseback via the Edirne Gate, visiting his ancestors’ graves and especially St. Sophia, before returning to Topkapı Palace.

We know very little about the actual ceremony at Eyüp until the beginning of the 20th century and the girding ceremony for Sultan Mehmed V, when non-Muslims were invited to attend (See The New York Times, 10 May 1909). As a result, we know the sultan first attended a prayer service in the mosque before he was girded with the sword, the latter ceremony only taking about 15 minutes. The last sultan to be girded with the sword of Osman was Mehmed VI in 1918 and this time, the last time, the ceremony held was filmed. The Ottoman dynasty’s rule ended in 1922 with the end of the empire.

Eyüp al-Ansari’s final resting place

Eyüp al-Ansari’s final resting place A ‘coronation’ mosque

A ‘coronation’ mosque