Experts and locals scrambling to document Syria’s heritage

BEIRUT – The Associated Press

AP Photos

Scientists are slipping 3-D cameras into Syria to local activists and residents to scan antiquities. A U.S.-funded project aims to provide local conservators with resources to help safeguard relics. Inside Syria, volunteers scramble to document damage to monuments and confirm what remains. The rush is on to find creative and often high-tech ways to protect Syria’s millennia-long cultural heritage in the face of the threat that much of it could be erased by the country’s war, now in its fifth year.

The rush is on to find creative and often high-tech ways to protect Syria’s millennia-long cultural heritage in the face of the threat that much of it could be erased by the country’s war, now in its fifth year. The campaigns are also fraught with risks. Getting supplies to activists on the ground can expose them to retribution from Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) militants or others suspicious of outside powers.

As a result, the various efforts underway are mostly cloaked in secrecy, with their organizers reluctant to give specifics on their activities for fear of endangering those on the ground.

“I don’t want to be having this conversation with somebody three years down the road, and they say, ‘Gee why didn’t you start in 2015 when they [ISIL] only controlled three percent of the sites’,” said Roger Michel, whose Million Image Database, an Oxford Institute of Digital Archaeology project, began distributing hundreds of 3-D cameras around the region to activists.

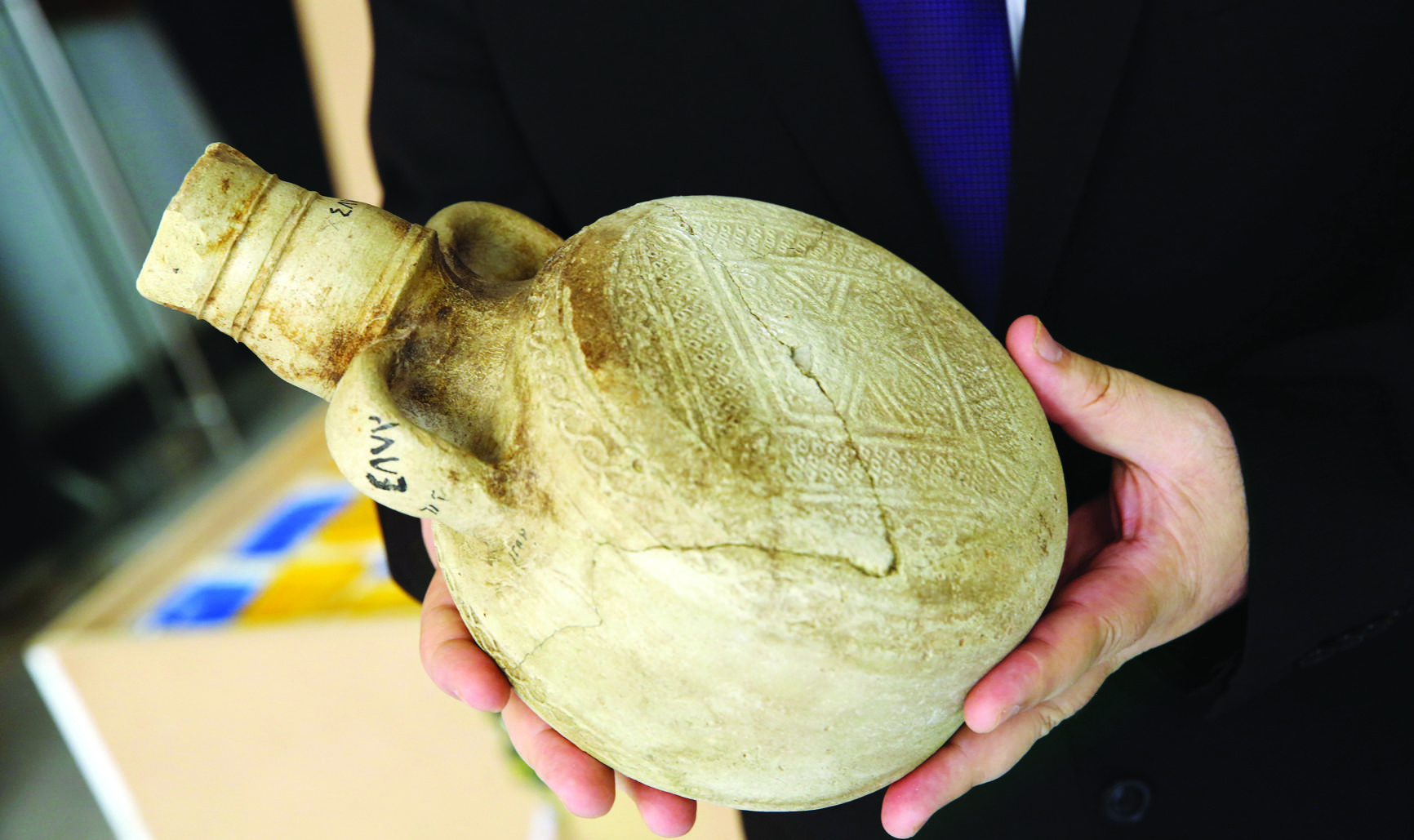

Historical sites have been damaged constantly since the war began, struck by shelling and government airstrikes or exposed to rampant looting. Syrian government officials already say they have moved some 300,000 artifacts from around the country to safe places over recent years, including from ISIL-controlled areas.

ISIL’s advances mean antiquities in Syria and Iraq face the danger not just of damage but of intentional eradication. The most stunning example came in the past month, when the militants blew up two famed temples in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. Satellite images showed that the two temples, which had survived for nearly 2,000 years, were reduced to rubble.

The Million Image Database project, which is backed by UNESCO, aims to “flood the region” with low-cost, easy-to-use 3-D cameras, delivered to activists to document antiquities in their area, Michel said.

Nearly 1,000 cameras have already been deployed or are on their way, not only to Syria, but also Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Turkey, Jordan and Egypt. The aim is to distribute 5,000 cameras region-wide by next year, at a total coast of $3 to $6 million.

Camera users can then upload the pictures or videos to the project’s website.

A separate project would carry out far more detailed scans of antiquities in Syria and Iraq using laser scanners. The scanners bounce lasers off the surface of objects in the field, measuring millions of points a second to create a data set known as a point cloud. The data can be used to create 3-D images accurate to two or three millimeters to create models or virtual tours of the sites or allow full-scale reconstructions.

The project, called “Anqa,” the Arabic word for the phoenix, the legendary bird that rises from the ashes, aims to laser-scan 200 objects in Syria, Iraq and other parts of the region, said its director Ben Kacyra, of the California-based scanning company CyArk.

Another campaign is taking a more low-tech approach aiming at directly protecting at least some sites. A project by the American Schools of Oriental Research provides supplies and funding to local experts and volunteers for things like crates to store artifacts or sandbags to pack around unmovable structures to give some protection against shelling or bombs, said LeeAnn Gordon, project manager for Conservation and Heritage Preservation at ASOR, which receives U.S. State Department funding.

“What we are really looking for is these kinds of small projects that can have big impact,” Gordon said. “Syria has so much. In my opinion, there is still more intact than there is destroyed.”