Exhibition removes veil of history obscuring Anatolian minorities

ISTANBUL-Hürriyet Daily News

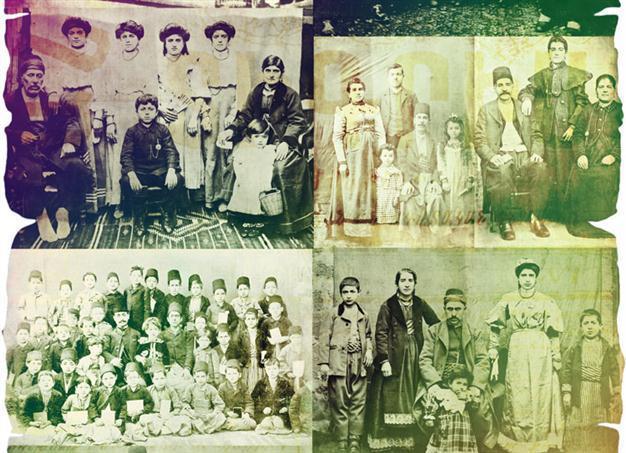

The exhibition in Istanbul’s Tophane provides a rare glimpse into the history of Armenians living in Diyarbakır.

The Birzamanlar (Once Upon a Time) Publishing House has launched a photography exhibition in Istanbul’s Tophane neighborhood, providing a rare glimpse into the history of non-Muslim minorities living in the southeastern province of Diyarbakır.“Official history teaches us that all these cities were created by the Turks, and that all the fair deeds of the past were done by them. Those who are not Turks or Muslims are depicted as unfavorable figures,” Osman Köker, the owner of the Birzamanlar Publishing House, recently told the Hürriyet Daily News. “The cultures, faiths, traditions and genetics of the peoples of old are also part of the reality we call the Turkish nation.”

Cultural Diversity in old Diyarbakır

Around 200 photographs compiled from 40 different sources are on display at the “Cultural Diversity in Old Diyarbakır” exhibition, which is being jointly organized by the Birzamanlar Publishing House and the Anatolian Culture and Global Dialogue, an Istanbul based nongovernmental organization. The exhibition at Tophane’s Tütün Deposu began Feb. 10 and will continue until March 10.

“Eastern Anatolia was much richer at the turn of the 20th century than it has been in the Republican period, both culturally and materially,” Köker said, adding that the memories of old were still very much alive in Anatolia.

The exhibition, which relates the lives and commercial contributions of Diyarbakır’s long forgotten peoples, such as the Armenians, Syriacs, Chaldeans, Anatolian Greeks and the Yezidis, also features explanatory notes in Turkish, English and Kurdish.

“Armenian newspapers were published and theaters [staged plays] not merely in Diyarbakır, but also in many other [nearby] places like Elazığ, Erzurum, Van and Erzincan. There were many factories [making various kinds of produce] ranging from the silk industry to metal wares. These [factories] did not [produce] solely for the domestic market but also for exports,” Köker said.

Turkish people are now striving to learn about the truth instead of the bragging of official history, he said. “All of us have grown weary of such vein boasting.”

Old shopkeepers and artisans in the region readily confide they had learned their skills from Armenians and Syriacs, he said.

Köker said they had already taken the exhibition to many different corners of the world, including Armenia and that Anatolian peoples had always shown great interest in the exhibition at every stop.

“Diaspora Armenians know precious little of the things they see in the exhibitions. They see the concrete [images] of things that seem to them like the stuff of legends. Moreover, they are nonplussed that this project has been undertaken by a person of Turkish-Muslim identity from Turkey,” he said.

Köker also said they had conducted research in the Orlando Carlo Calumeo Collection, the

Boston-based Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archive, as well as the Annuaire Oriental, an annual commercial almanac that has been published since the mid-19th century, while they were preparing for the exhibition.

“When [we] examine the 1914 edition of the commercial almanac’s section on Diyarbakır, [we see that] many trades people were Armenian, including [the owners of] all of the 12 firms dealing in jewelry, 10 of 11 stone masons, nine copper merchants and 10 firms that produced silk fabric. The city’s sole hotel was also operated by an Armenian,” he added.

The Birzamanlar Publishing House has also attracted a lot of attention both in Turkey and abroad with other exhibitions, such as the “Armenians in Turkey 100 years ago,” and the “Freedom’s Heirloom – Postcards of the Constitutional [Period].”