Egyptian ultras again on focus on both end of street protests

James M. Dorsey

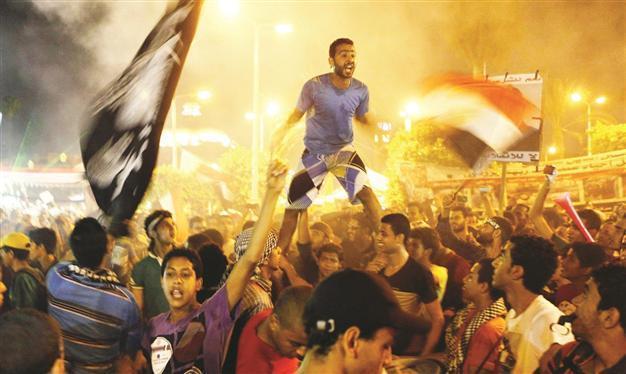

Some ultras join the supporters of ousted Egyptian President Mohamed Mursi shout slogans and wave flags around Cairo University and Nahdet Misr Square where they are camping in Giza. REUTERS photo

A football brawl last year in which more than 70 militant fans died galvanized significant numbers of Egyptians against the military and security forces, accelerating the army’s desire to turn power over to an elected government.Eighteen months later, mass protests, involving the Muslim Brotherhood, non-Brothers and militant, battle-hardened football fans are opposing the military ouster of elected president Mohamed Morsi and the subsequent brutal crackdown on the Brotherhood, both of which were backed by a significant segment of Egyptian society.

The ingrained resistance to military rule and arbitrary security forces of many football fans and the youth groups that formed the backbone of the popular uprising that forced President Hosni Mubarak out of office in early 2011 is again visible in more than the fact that it has been adopted by a far wider section of the Egyptian public. It has been reinforced by what many Egyptians perceive to be a restoration of repressive features of the Mubarak era.

Events in recent days have demonstrated that while Egypt remains deeply divided, public opinion is fluid and the backing for the military coup against Morsi is fragile and conditional. The first cracks in that support have manifested themselves despite a significant number of Egyptians egging the military and the security forces on to be even tougher in their crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood.

In quick succession, various prominent supporters of the coup have resigned or sought to distance themselves from the brutality of the crackdown that has caused the death of at least 700 people.

Mohammed ElBaradei, an international civil servant and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, resigned as vice-president of the military-appointed government that succeeded Morsi because in his words “the beneficiaries of what happened … are those who call for violence, terrorism and the most extreme groups.”

Khaled Daoud, spokesman of the National Salvation Front, a major pro-military civic group, stepped down days later because a majority of the front refused to condemn the bloodshed at the hands of the security forces. His successor, Ahmed Howari, in one of his first public statements was careful to balance his remarks with expressions of sincere regret about the way security forces were seeking to repress the opposition to the military.

The impact of the fans goes further than the fact that their anti-military attitudes have gained greater currency because of qualms about military disruption of a democratic process, even if Morsi had succeeded in becoming widely reviled after only a year in office, and security force brutality that was one of the main drivers of Mubarak’s ousting. It is also evident in various forms of pro-Morsi protest, including the jumping up and down while chanting, a typical way for militant football fans or ultras to support their club, and the waving of flags with a skull and crossbones emblem. By the same token, Egypt’s deep polarization as well as the crisis in Egyptian football that was accelerated by last year’s deadly brawl in Port Said has not left the militant football fans untouched. While the ultras as organizations have refrained from joining the fray, many of their members and leaders have, reflecting the gamut of political views in their ranks.

Ironically, many Ultras White Knights, the fan group of storied Cairo club al-Zamalek SC, which traces its root to support of the monarchy that was toppled by a military coup in 1952 and replaced by Arab nationalist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, an army colonel, who became the club’s president and brutally repressed the brotherhood, have joined the pro-Morsi protests. But the Black Bloc, the vigilante group that emerged last year to defend anti-Morsi protesters against both the security forces and brotherhood attackers, are believed to be siding with the police in the crackdown on the brotherhood.

The UWK’s arch rivals, Ultras Ahlawy, the fan group of al-Ahly SC, historically the nationalist club, this week issued its first anti-brotherhood statement. The statement ended the group’s silence with regard to the government while Morsi was in office. By refraining from attacking the government, the group had hoped that harsh verdicts would be served in the trial of those responsible for the deaths in Port Said. It got only partial satisfaction. While 21 supporters of Port Said’s al-Masri SC club were sentenced to death, seven of the nine security officials were acquitted.

“The ultras have become fascists. Like Egypt, they have collapsed. They have no values and no real beliefs,” said a former ultras leader who left his group in disgust at the political turn it had taken.

In a perverse way, the ultras’ dilemma is not dissimilar from that of the brotherhood. Neither could decide what it really was. The brotherhood has yet to make up its mind what it is: a social or a political movement. That decision may become easier if it survives the current crackdown and potentially emerges strong enough to negotiate terms of a political solution to Egypt’s crisis.

The ultras refused to acknowledge that they were as much about politics as they were about football. Their battle for freedom in the stadiums and their prominent role in the toppling of Mubarak, the opposition to the military rulers that succeeded him and the Morsi government made them political by definition. Yet, those who populated their rank and file were united in their support for their club and their deep-seated animosity toward the security forces but on nothing else.

The ultras’ fate could change if Egypt continues down the road it has embarked on of a restoration of Mubarak’s police state. Repression with little more than a democratic facade could again turn stadiums into political battlefields against military and security force control whether overt or behind-the scenes; brutal and unaccountable security forces; and autocratic government masked by hollowed-out democratic institutions.

“I’m afraid of the return of the military state. That is not what I fought for in the stadiums and on Tahrir Square. I’m also afraid of the brotherhood. It’s a choice between two evils. If you ask me now, I’d opt for the military, but that could well change once this is all over,” the former ultra said.