Driven by consumers, US inflation grows more persistent

WASHINGTON

U.S. inflation is showing signs of entering a more stubborn phase that will likely require drastic action by the Federal Reserve, a shift that has panicked financial markets and heightens the risks of a recession.

Some of the longtime drivers of higher inflation, spiking gas prices, supply chain snarls, soaring used-car prices, are fading. Yet underlying measures of inflation are actually worsening.

The ongoing evolution of the forces behind an inflation rate that’s near a four-decade high has made it harder for the Fed to wrestle it under control. Prices are no longer rising because a few categories have skyrocketed in cost. Instead, inflation has now spread more widely through the economy, fueled by a strong job market that is boosting paychecks, forcing companies to raise prices to cover higher labor costs and giving more consumers the wherewithal to spend.

On Sept. 13, the government said inflation ticked up 0.1% from July to August and 8.3 percent from a year ago, which was down from June’s four-decade high of 9.1 percent.

But excluding the volatile categories of food and energy, so-called core prices jumped by an unexpectedly sharp 0.6 percent from July to August, after a milder 0.3 percent rise the previous month. The Fed monitors core prices closely, and the latest figures heightened fears of an even more aggressive Fed and sent stocks plunging, with the Dow Jones collapsing more than 1,200 points.

The core price figures solidified worries that inflation has now spread into all corners of the economy.

“One of the most remarkable things is how broad-based the price gains are,” said Matthew Luzzetti, chief U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank. “The underlying trend in inflation certainly has not shown any progress toward moderating so far. And that should be a worry to the Fed because the price gains have become increasingly demand-driven, and therefore likely to be more persistent.”

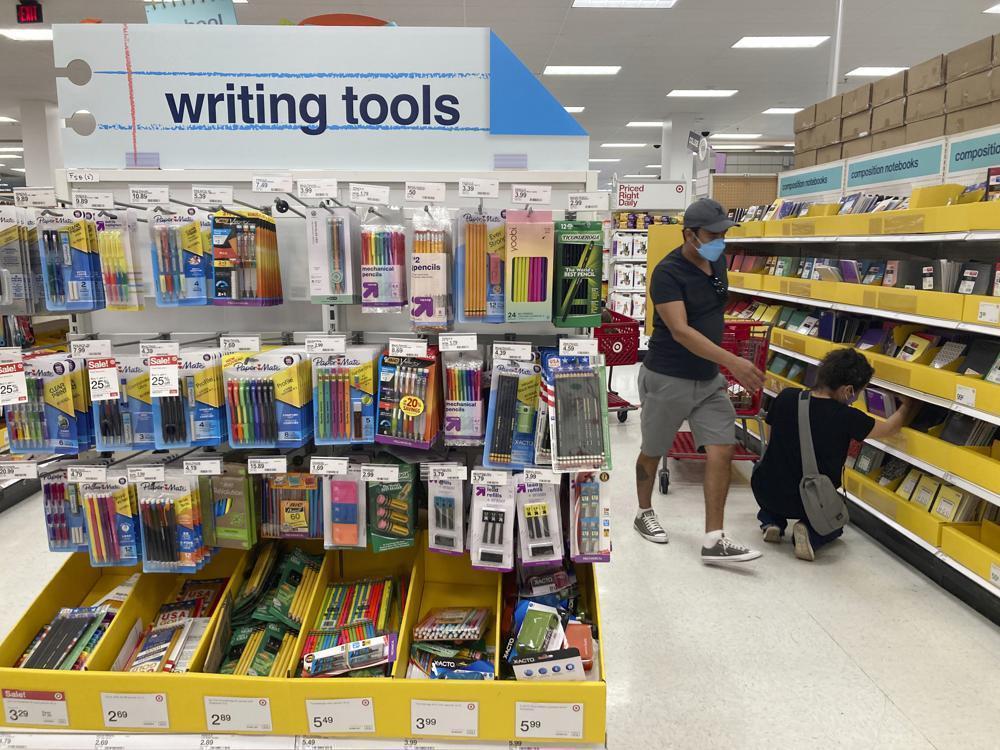

Demand-driven inflation is one way to say that consumers, who account for nearly 70 percent of economic growth, keep spending, even if they resent having to pay more. In part, that is because of widespread income gains and in part because many Americans still have more savings than they did before the pandemic, after having postponed spending on vacations, entertainment, and restaurants.

When inflation is driven mainly by demand, it can require more drastic action from the Fed than when it’s driven mainly by supply shocks, such as an oil supply disruption, which can often resolve on their own.

Economists fear that the only way for the Fed to slow robust consumer demand is to raise interest rates so high as to sharply increase unemployment and potentially cause a recession. Typically, as fear of layoffs rises, not only do the jobless reduce spending. So, too, do the many people who fear losing their jobs.

Some economists now think the Fed will have to raise its benchmark short-term rate much higher, to 4.5 percent or above, by early next year, more than previous estimates of 4 percent. (The Fed’s key rate is now in a range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent.) Higher rates from the Fed would, in turn, lead to higher costs for mortgages, auto loans and business loans.