Crises in emerging markets and China give frightening signals

Mustafa Sönmez - mustafasnmz@hotmail.com

AFP Photo

The global economy entered 2016 with the image of weak recovery in developed countries. However, the weak and fragile outlook in emerging countries, of which Turkey is one, particularly with the economic slowdown, scares everybody. Some are arguing that the world economy is about to enter a crisis worse than the major global one in 2008.

Frightening recession

The global economy is experiencing the effects of the new state of U.S. monetary policy and the slowdown of the Chinese economy. The moderate recovery outlook in developed economies is not regarded as very soothing. In those raw material and energy (commodity) producer/exporter countries and in those countries which have strong ties with China, growth has slowed down and fragilities have increased. The slowing in the growth of “emerging economies,” also called “southern countries,” is becoming more visible every day and the global economy looks as if it is now facing a crisis at the “periphery” before the “center” can heal its wounds. It is estimated that the world economy grew 3 percent in 2015. This is not a very satisfying result. This result was due to the slowing down of the economies of several countries, primarily China, the deterioration of certain basic economic indicators of the U.S. in the first half of the year and increasing geopolitical risks. The low-course of oil and commodity prices as of mid-2014 supported the growth of developed economies but slowed down the growth of commodity-exporting countries. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) must have wished to keep its optimism when it revised its world growth forecast to 3.1 percent; it has kept its 2016 target at 3.4 percent, for now.

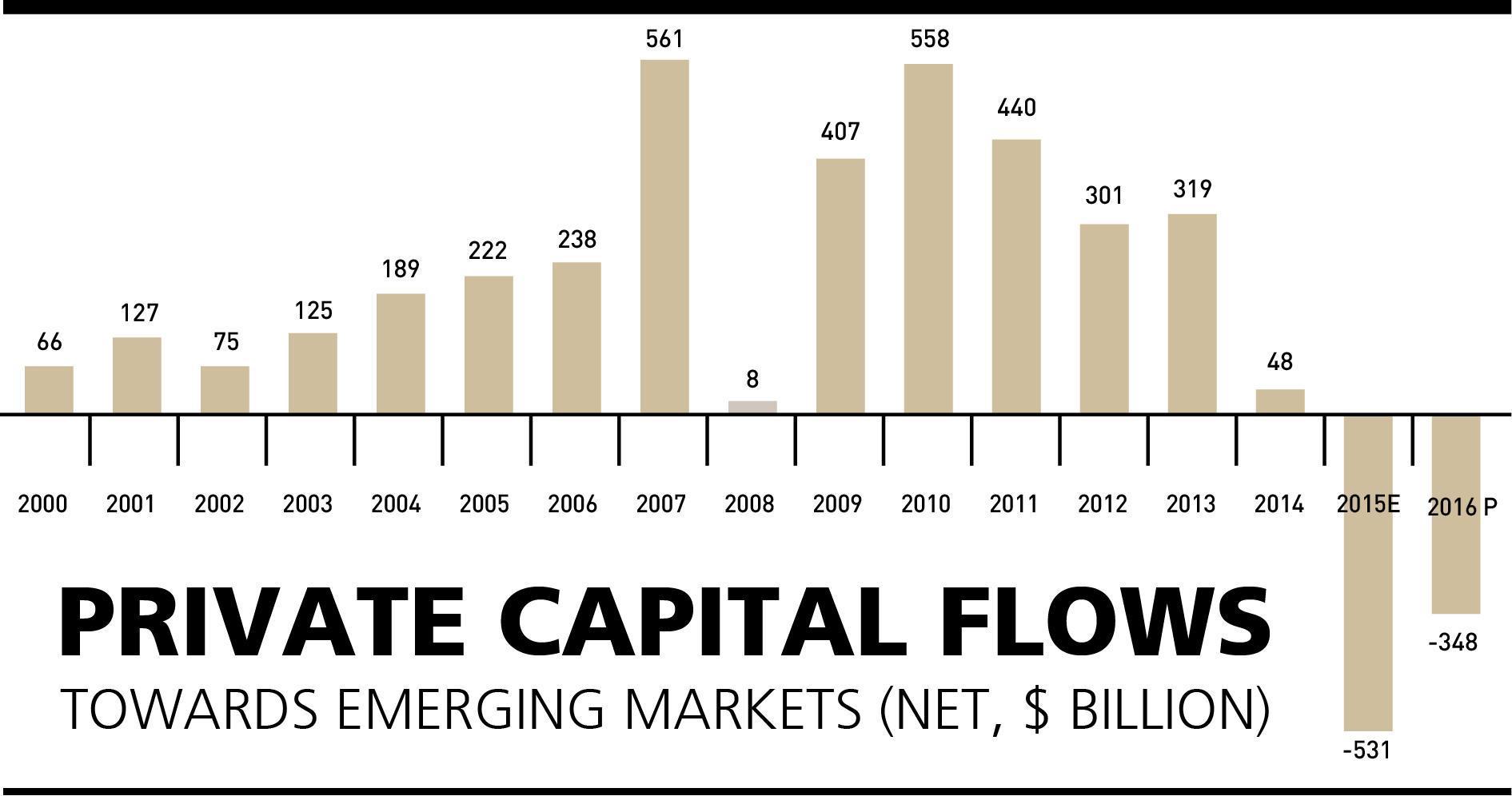

The emerging periphery countries grew after 2000 with the foreign capital pouring into them. In the 2008-2009 crisis, when the entire capital was introverted, short-term capital withdrawals were experienced in emerging countries and there were currency and economic fluctuations.

However, central countries opted for expansionary monetary policies to ease the crisis, causing a portion of this money to flow into emerging countries again; the means to grow again between 2010 and 2013 were created. However, following the announcement of the U.S. Central Bank’s (Fed) decision to increase rates in mid-2013, those funds that had temporarily parked in emerging countries turned their faces to the U.S., increasing foreign resource withdrawals from emerging countries.

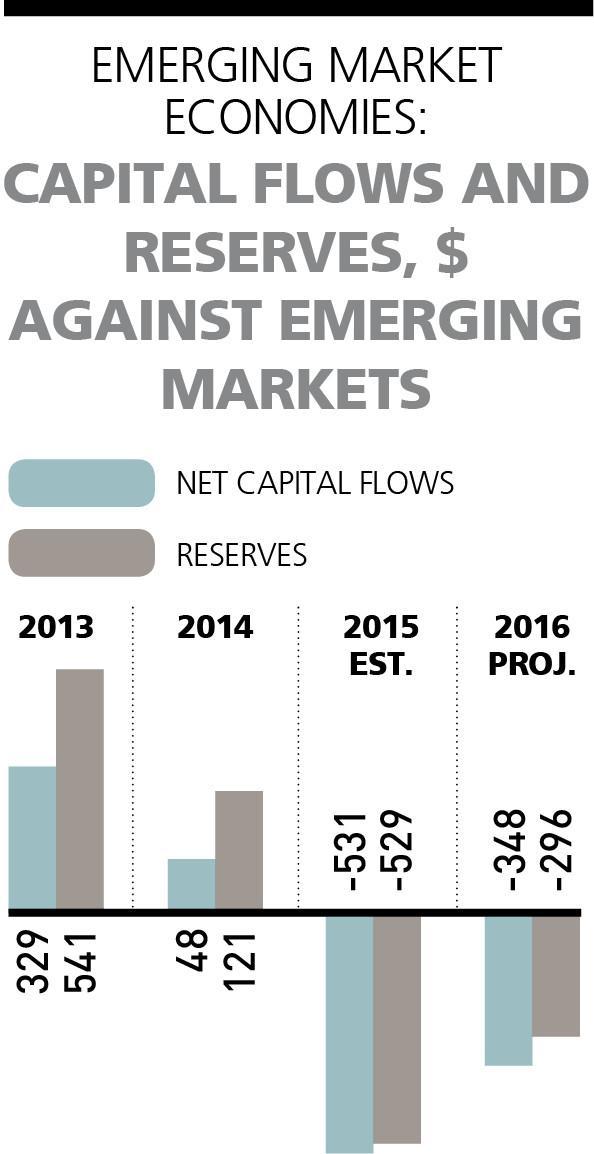

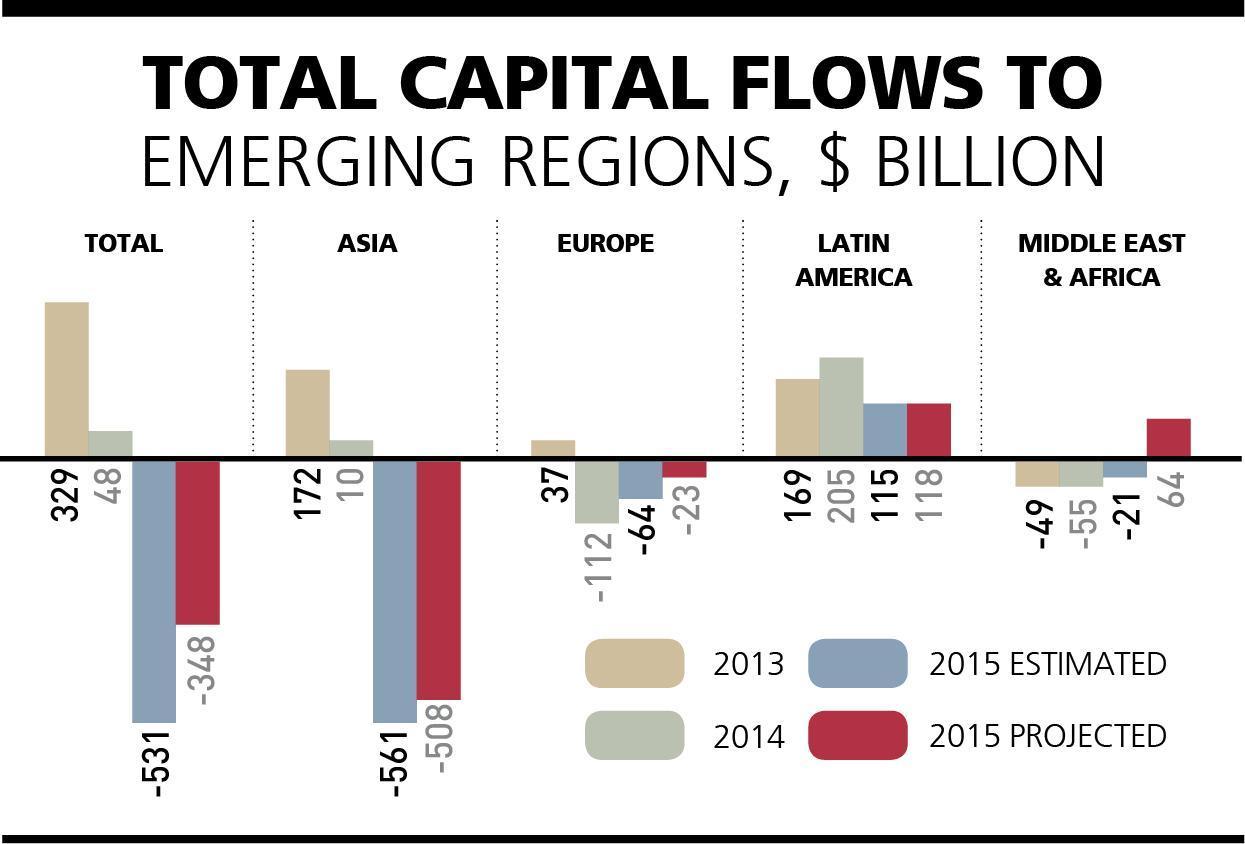

With the Fed starting its rate hikes in December 2015, the slowdown of the Chinese economy, the drop in commodity prices, increasing financial fluctuations and decreasing global demand and commerce resulted in weak capital inflows to emerging countries.

According to data from the Institute of International Finance (IIF), in 30 emerging countries, including Turkey, an annual average inflow of $200 billion from foreign resources occurred between 2000 and 2007. With the global crisis of 2008, this suddenly stopped and went down to $8 billion. However, with the money pumped by central countries into emerging markets the annual foreign inflow in the 2009-2013 period went up to $407 billion. However, with the Fed signaling rate hikes, the inflow in 2014 dropped to $48 billion. In 2015, instead of inflow, intense withdrawals which reached $513 billion were experienced. The withdrawals will continue in 2016 also. The presidential elections to be held in 2016 in the U.S., the referendum over EU withdrawal to be held in the U.K. and similar uncertainties and increasing geopolitical risks affect the capital traffic and the capital owners’ appetite. The forecast for 2016 is that an additional $350 billion foreign capital will withdraw from emerging countries.

What it means to live a dolce vita with abundant foreign resources is best known in the Turkish experience. The sweet wind brought into the economy looked as if it was permanent, but it was temporary and this has enabled the Justice and Development Party (AKP) to win one election after another. However, now, in Turkey, and other emerging countries, when capital inflow left its place to withdrawals, the climate in the economy also started changing. Countries are trying to close their current account deficits in unsustainable ways but this road does not prevent their local currencies from losing value against the dollar.

The IIF data draws attention to the fact that with the loss of foreign resources in 2015, which exceeded $530 billion, the reserves of 30 emerging countries eroded about the same size. In 2016, an erosion of nearly $300 billion is expected.

Fear of China

The Chinese economy, which was growing over 10 percent, went down to 6 percent. In the 1980s China made use of its cheap labor and entered every market with this competitive power. It grew based on exportation. With the 2008 crisis China’s export markets shrank. Its growth rate went down to single digits. China did not change its growth strategy, thinking this was temporary. It opted to compensate its growth loss through investments and this step caused an extreme capacity expansion in China. It did not help; capital withdrawal began.

Nowadays, the outflow of foreign currency in China is a major problem. It looks possible to slow this down by restricting capital movements. It may prevent the erosion of reserves. But when this is done, liberation would be given up. With such restrictions the economy would lose all its attraction in terms of capital inflow.

While it has been wondered how China can overcome these issues, it has also been wondered what the other emerging countries which sell raw material and energy to China would do in the void created by this country. Shrinkage and chaos began in these countries, particularly in Brazil and South Africa.

And Turkey

And Turkey

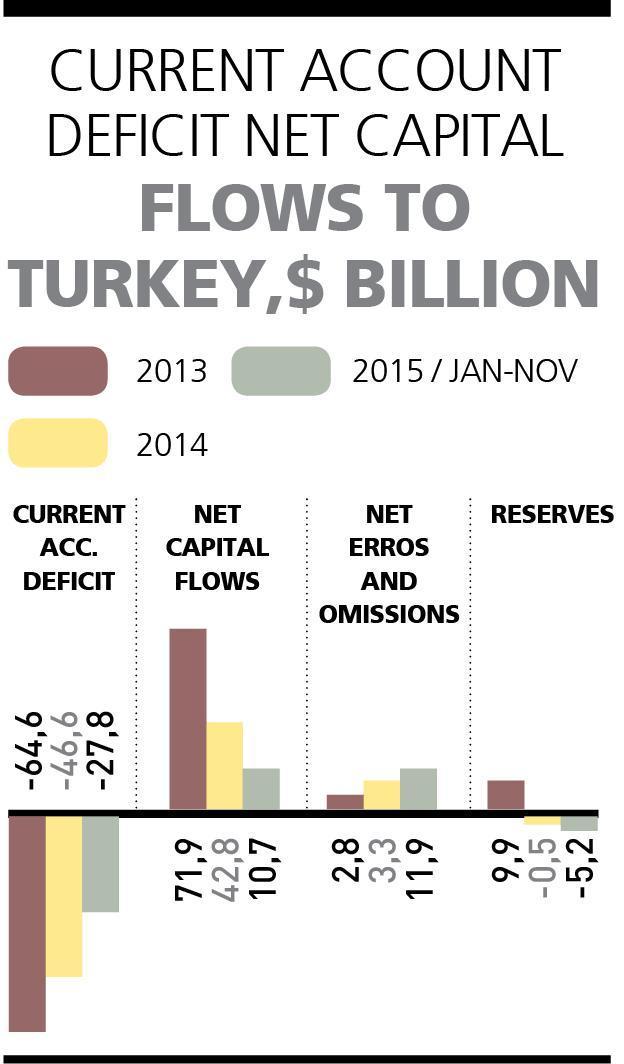

Turkey has started receiving its share of risks that other emerging countries are facing. Turkey, which has grown for 10 years with foreign capital inflow, has shifted to the 2-3 percent growth path in recent years. This year, with the effect of the rise in political and geopolitical risks, there is a radical fall. The current account deficit of the already shrunken economy has decreased but again looks as if it will exceed $30 billion annually.

However, the share of foreign resources in financing this deficit had fallen under 40 percent. In 2014, Turkey had $43 billion in foreign resources; in 2015 this figure barely made $12 billion. This means a drop of more than 70 percent. How was this financed? Of course from reserves and from resources named “net errors and omissions.” But, again, it is having a hard time trying to keep the value of the Turkish Lira at 3 liras per dollar.

Despite the falling energy prices, the growth target of 3-4 percent Turkey has aimed at will again bring at least a current account deficit of $30 billion. In this case, from which sources will this deficit be financed? If so, then how high will the dollar/Turkish Lira go? Will rates be increased for foreigners to come, and if so, how will growth happen with such high rates?

At this juncture, where foreign capital inflow has weakened and financing costs have hiked because of increased risk premiums, how will it be possible for Turkey to decrease its current account deficit, lower its inflation rate to reasonable levels, increase its industry production capacity and advance its production quality while accelerating structural reforms? Especially under the conditions of 2016, when domestic, political and geopolitical risks seem to never cease…

These are a number of questions which have emerged with the crisis “of the south” starting to show its effects in Turkey and most probably new ones will be added in the coming days…

The global economy entered 2016 with the image of weak recovery in developed countries. However, the weak and fragile outlook in emerging countries, of which Turkey is one, particularly with the economic slowdown, scares everybody. Some are arguing that the world economy is about to enter a crisis worse than the major global one in 2008.

The global economy entered 2016 with the image of weak recovery in developed countries. However, the weak and fragile outlook in emerging countries, of which Turkey is one, particularly with the economic slowdown, scares everybody. Some are arguing that the world economy is about to enter a crisis worse than the major global one in 2008.

And Turkey

And Turkey