Construction forges ahead in debt, industry left behind

Mustafa Sönmez - mustafasnmz@hotmail.com

Hundreds of new buildings are arising, particularly in so-called 'urban transformation' projects, such as here in the Tarlabaşı neighborhood right across from the touristic İstiklal Avenue. REUTERS Photo / Murad Sezer

The Central Bank announced last week that, as of end of September, the Turkish private sector’s long-term loans have reached $164 billion. Indeed, this is not even the entire outstanding external debt, but only a part of it. Alongside long-term debts, the private sector also has short-term debts of $112 billion, while the public sector has $108 billion long-term and $18 billion short-term debts, totaling $126 billion. This means that Turkey’s total outstanding external debt is approaching $402 billion, a burden that is more than 50 percent of Turkey’s national income. Also, 40 percent of these loans have to be renewed and paid back within 12 months, which imposes a significant amount of fragility and pressure on Turkey’s economy.

For a country with a domestic savings rate of only 15 percent, it is essential to find external sources, or in other words, use others’ savings for its growth. But isn’t it also an important question where the source of this debt is taken from, and whether it is used properly or not?

The private sector owns 69 percent of the outstanding external debt, or $402 billion of it, while the public sector has the other 31 percent. In order to understand the source of this debt, how it has been used and whether it has been used properly, it would be appropriate to look at the sector analyses of the external credits that the private sector has obtained.

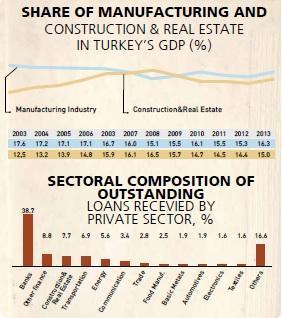

The composition of the private sector’s long-term loans indicates a source mostly from the construction and service sectors, more than production sectors. Almost 39 percent of the long-term loans were used by banks. Other financial institutions, (insurance companies, holdings, etc.) have used nearly 9 percent of credits. Financial institutions offer these loans that they obtained externally as loans to domestic consumers and firms. Consumer credits have a share of nearly 40 percent, and most of them are used on mortgages. The fact that the sector which uses the most credits is the construction/real estate sector does not come as a surprise, especially to those living in Istanbul. Mortgages provided by banks are accompanied by loans offered to the construction-real estate sector, which make up 7.7 percent of credits.

While the construction sector and its complementary real estate sector share 7.7 percent of the total outstanding long-term external debts of the private sector, transportation firms, predominantly civil aviation firms, have nearly a 7 percent share in loans. The rapidly growing Turkish Airlines (THY) is also growing with considerable external debts. Energy firms that use external financing for privatized electricity distribution and power plants have a share of the long-term debt stock approaching 6 percent. On the other hand, manufacturing firms have stayed below 14 percent in the usage of external long term credits. Ten years ago, this sector was using up to 30 percent of all loans. As can be seen, loan usage for the manufacturing sector has dropped significantly; on the other hand, the construction sector has shined. As a matter of fact, we can also see this reflected in the contributions of the two sectors to Turkey’s Gross Domestic Product figures. In 2003, the contribution of the manufacturing sector to national income was nearly 18 percent, but it then began to decrease. By 2013, it had gone down to 15 percent (this year, though, it is expected to be 16 percent). Meanwhile, the construction sector and its complementary real estate sector have risen considerably in their contributions to national income. In 2003, their contribution was 12.5 percent, which increased in the following years to 15 percent, catching up with the added value of the manufacturing sector.

Why construction? The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) government has prioritized the construction sector, making it a phenomenon, especially in Istanbul. The Housing Development Administration (TOKİ), reporting to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, became an important institution in 2003. When the General Directorate of Plots Office, which managed all public plots, was merged with TOKİ without taking one lira from the budget, TOKİ became the possessor of an incredible asset. There was only one thing to do now: To offer the most prestigious plots with the highest returns to contractors. “Build luxury houses. We will provide the land, you will build it. We will share the income in half,” was the general calling, and this offer was taken up immediately. Ağaoğlu, Varyap, Kuzu, Aşçıoğlu and the like started rapidly building luxury houses in areas such as Ataşehir, Ataköy and Bahçeşehir in Istanbul. In turn, TOKİ built buildings in Anatolia with the income generated by them. As a result, throughout 13 years of AKP government, nearly 600,000 TOKİ units have been built, in addition to numerous mosques, stadiums and even police stations.

Banks further fueled the sector with their home loans. When homes started to become more than just accommodation and began to generate income, the popularity grew.

Construction-oriented growth has increased the number of people voting for the AKP government. One can see the effect of a booming construction sector reflected in the AKP’s voter base, which has inflated from 30 percent to 50 percent. While construction motivated the manufacturing sector, producing cement, bricks, glass and fittings, it also created employment opportunities in both sectors. Jobs were created for the unemployed, even though they were unsecured and paid minimum wage. Despite the risk of falling victim to a workplace accident, when one more person was able to find a job in households, the sympathy of the voter also increased.

Most importantly, construction created the opportunity for the AKP to make its own bourgeois. Big holdings such as Limak, Cengiz, Kolin, Kalyon, Maya, Torunlar and Çalık, names we hear frequently in both private and public infrastructure investments, have grown fat thanks to increased construction during the AKP era.

It is not a coincidence that in addition to construction, these firms have also won many other privatization tenders, especially in electricity distribution grids and power plants.

Even though construction has carried the AKP and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan onwards and upwards, today it has become a problem. The reason is that construction is a domestic sector; it does not generate much foreign currency. Only $3 billion worth of foreign currency are obtained annually from construction, whereas Turkey’s exports are nearly $150 billion, and this is mostly provided by the manufacturing sector. As the foreign currency-generating industrial sector lagged behind, sectors that are not engaged with foreign currency, such as construction or civil aviation, have caused Turkey to stumble through the problem of a foreign currency deficit. This chronic current account deficit, which has reached 6-7percent of national income, has left the situation very fragile.

Now, strategies are being developed to make the neglected and offended manufacturing sector stand on its feet again, but it is not quite certain yet by what method or how long it will take for those who got accustomed to the sweet earnings of construction to transform into industry, and how this transformation can be encouraged.

The composition of the private sector’s long-term loans indicates a source mostly from the construction and service sectors, more than production sectors. Almost 39 percent of the long-term loans were used by banks. Other financial institutions, (insurance companies, holdings, etc.) have used nearly 9 percent of credits. Financial institutions offer these loans that they obtained externally as loans to domestic consumers and firms. Consumer credits have a share of nearly 40 percent, and most of them are used on mortgages. The fact that the sector which uses the most credits is the construction/real estate sector does not come as a surprise, especially to those living in Istanbul. Mortgages provided by banks are accompanied by loans offered to the construction-real estate sector, which make up 7.7 percent of credits.

The composition of the private sector’s long-term loans indicates a source mostly from the construction and service sectors, more than production sectors. Almost 39 percent of the long-term loans were used by banks. Other financial institutions, (insurance companies, holdings, etc.) have used nearly 9 percent of credits. Financial institutions offer these loans that they obtained externally as loans to domestic consumers and firms. Consumer credits have a share of nearly 40 percent, and most of them are used on mortgages. The fact that the sector which uses the most credits is the construction/real estate sector does not come as a surprise, especially to those living in Istanbul. Mortgages provided by banks are accompanied by loans offered to the construction-real estate sector, which make up 7.7 percent of credits.