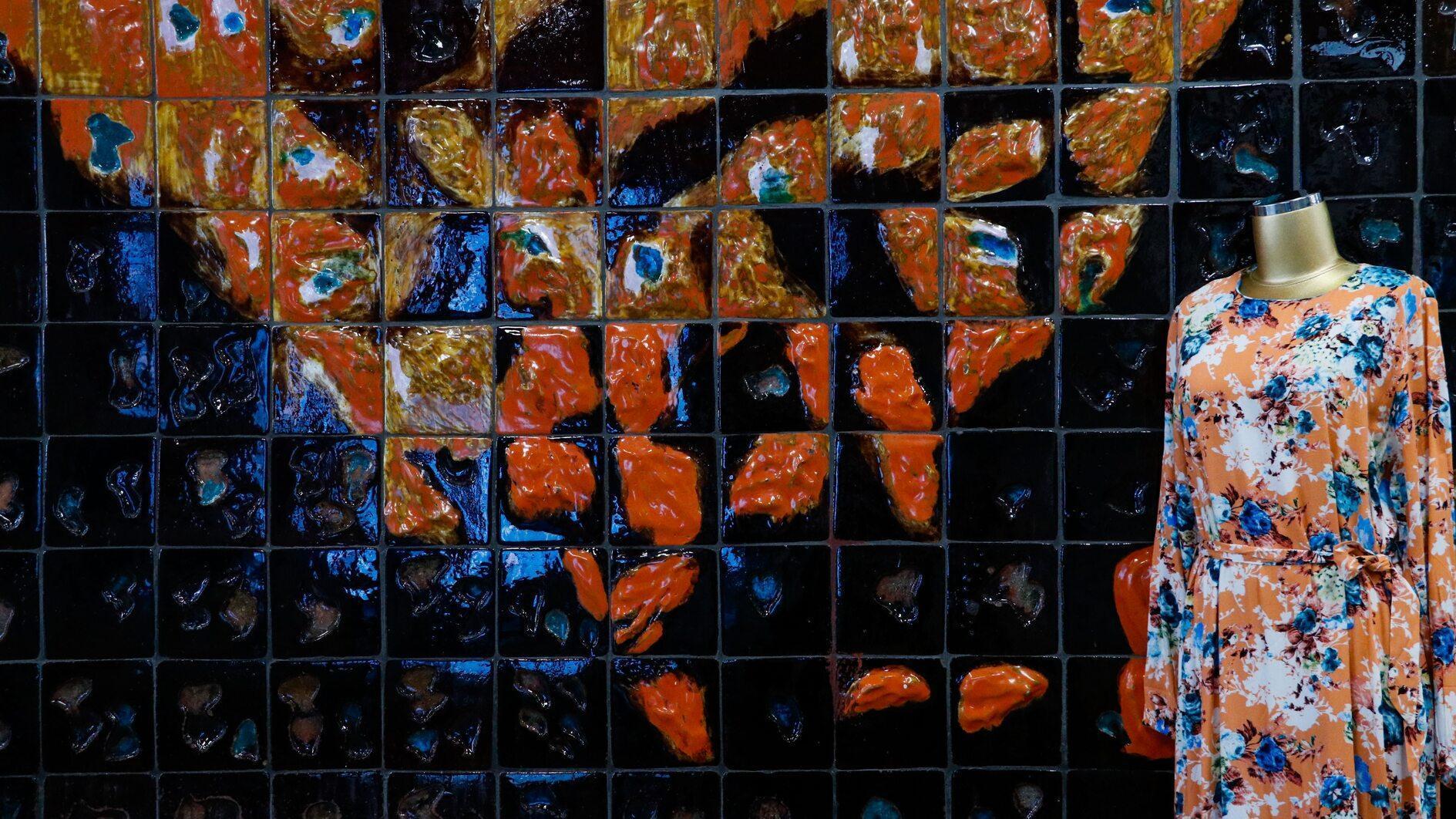

Art historian Nurtaç Buluç brings together ceramic, relief and mosaic panels found in architectural structures between 1950 and 1990 in the database "City Panels" to shed light on the cultural memory of the period.

Buluç explained that the idea of creating a database arose from her interest in ceramics and mosaics, adding that architecture and the arts are an integral part of life.

"We tried to document the structures that we think reflect the cultural memory of their periods. In addition to digital archiving, we turn these panels into stories and present them on social media,” Buluç said.

Noting that they also make academic publications, she said: "For this reason, I can say that we have a multi-layered project. Our purpose is to publish our data on the website for researchers and to prevent these works from being forgotten even if they are physically lost."

Buluç stated that the idea for the "City Panels" project came up as an online archive of artworks found on architectural structures in 18 of the country’s 81 provinces, particularly from 1950 to 1990. She explained that the database was created using newspaper archives, sources from architecture magazines, and photos of the panels taken and submitted by art lovers.

Stating that they did start working professionally while carrying out the project and that they aimed to present the data to researchers through the most basic website, Buluç said: “For instance, we focused on the late 1940s and early 1950s, the years when many artists such as Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, Füreya Koral and Sadi Rıfat Diren created works. Of course, very few of these works made in the 1950s survived, as many of them have been destroyed. We can start documenting from the 1960s onward. We personally go to the structures and shoot the ones that still survive from the 1960s to 1990s. There are currently around 500 panels from 18 different cities on the website. I think around 100 of these 500 works have disappeared."

Buluç explained that thanks to the filters in the database in the design of the archive, researchers can access the works in the fastest way according to the construction material, location or artist of the work.

“While making these filters, we also created a mapping system. When researchers click on the website, by looking at Türkiye’s map, they can see which provinces, neighborhoods and districts have architectural works of art. In addition, we also created a bibliography,” she said.

Buluç emphasized that they based this archive on an academic and archival database, saying that they examined newspaper archives and academic publications.

Permission required

Speaking about the difficulties they encountered while carrying out the project, Buluç said, “We cannot take photos without permission in private or public buildings. This requires a permission process. Documentation also concerns people living in apartments because, during urban transformation, they worry that if the artworks on the building are registered, it will make the process of transformation more difficult. Since they do not know the importance of the panels that are works of art, these situations cause us trouble during documentation."

Buluç stated that another reason for trouble is not being able to find the works in their place due to urban transformation, natural and unnatural reasons even if they are informed about them.

"Even if there is a work of art, sometimes some parts of it can be removed and damaged. For instance, we went to document a ceramic panel in the elevator of a hotel in İzmir. Since the elevator was old, the panel was made accordingly, but since they removed and reinstalled the panel during the renovation, there was damage."

Stating that the anonymization of panels started in the 1960s and 1970s as a result of reconstruction and multi-story apartment buildings, Buluç said that artists did not sign the panels because they did not think they were producing a work of art and saw them as a way of making money.

Referring to Law No. 2863 on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets, which came into force in 1933, Buluç said that there was no specific decision for these panels and noted that thanks to the "City Panels" and its followers, in line with the decision taken by the Kadıköy Municipal Council, the decorative elements on the buildings to be demolished within the scope of urban transformation are now taken under protection.

“We are trying to bring visibility to works of art in public spaces. I hope this work will be an example for other municipalities,” she added.

Noting that their goal is to create an oral history archive on the history of contemporary Turkish ceramic art, Buluç said that they interviewed the second-generation artists who made these ceramic panels in İzmir in June and that they hope to expand the project even further.

She added that they also published the names of those who photographed and shared the panels with them on social media and noted that they received very positive feedback about the project.