Cezanne’s maverick side explored in first-ever US portrait show

WASHINGTON - Agence France-Presse

What happens when an artist who devoted most of his career to painting landscapes and still lifes turns to the people he knows best?

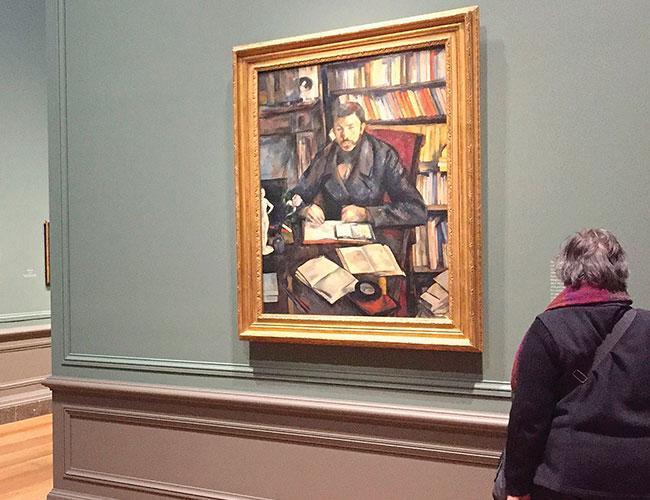

That is the central premise of an international show of 59 portraits by France’s Paul Cezanne opening on March 25 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the first ever dedicated to this aspect of his oeuvre.

Of the 1,000 paintings the 19th century Provencal painter created during his lifetime, only about 160 are portraits, mostly of his close friends, family and domestic servants.

But it is perhaps in that collection that the evolution of Cezanne’s individualistic, revolutionary vision is clearest, as he deconstructs space by boldly painting his wife with vanishing lips or applying layer upon layer of thick paint with a palette knife.

He may have studied Old Master works, but Cezanne “exploded” traditional ways of representing space and volume on a picture plane, said Mary Morton, co-curator of the show and head of the National Gallery’s department of French paintings.

Cezanne in many ways paved the way to modernism: even the pioneering Cubist Pablo Picasso, born 42 years after the French painter, called him the “father of us all.”

He relies on a “modernist understanding about how visual perception works... It’s not stable, it’s not linear, it’s not from a single point, it’s not coherent,” Morton told AFP.

Texture was also key. In “Antony Valabregue” (1866), the artist’s submission to the official Salon art exhibition in Paris critical for launching careers, Cezanne’s rough-hewn style is on full display.

The jury took the coarsely layered paint and the poet-sitter’s defiant and inelegant pose, fists clenched on his thighs, as a slap in the face -- and rejected it.

So roughly had Cezanne treated both the surface and the subject that one jury member commented he had painted not just with a knife but with a pistol.

“He is displacing the conventional place that you look for portraiture, which is the face, and that you’re expecting a likeness,” said Morton, who received a top French civilian honor this week for her contributions to the arts.

“It means that it’s perhaps in the color, it’s in the shape, it’s coming through in an unconventional way.”

Cezanne’s portraits of his wife, Hortense Fiquet -- who unlike her husband came from a modest background and lacked advanced education -- are especially confounding.

Often unflattering, the pictures show her with an angled oval face, her hair pulled back and parted down the middle. She never smiles.

Some are more sympathetic, such as “Madame Cezanne in a Red Armchair” (circa 1877) -- but that was painted before their marriage or shortly thereafter. In it she is shown seated on a plush red throne of a chair contrasting with a golden green and blue wallpaper pattern.

In one work from the “Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress” (1888-1890) series, she sits undisturbed in a blue room, her yellow chair and the wall tilting chaotically behind her.

Co-curator John Elderfield does not, however, see Cezanne’s renderings of his wife as commentary on a possible lack of affection in a couple that largely lived apart.

“If (art dealer Ambroise) Vollard is to be believed, he did more than 100 sittings for his portrait. She has about 30 portraits, so that’s 3,000 hours. Wouldn’t you be a bit fed up sitting there?” asked Elderfield, chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

“I think that even though facially it seems she’s expressionless, it doesn’t mean he doesn’t care about her.”

But Morton does not hesitate to factor in the quality of the relationship, or at least what’s known of it.

“There’s a really tough time after they’re married,” she said. “I think there’s tension and melancholy, and you get that in a lot of these. I don’t think he had an easy time with people.”

The show runs through July 1 in Washington, the last stop of a tour that took in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris and London’s National Portrait Gallery.