Celebrating Mevlana’s wedding day

Niki Gamm ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

The Mevlevis were one of a number of mystic sects that appeared following the rise of Islam in the seventh century. Scholars count 14 main sects.

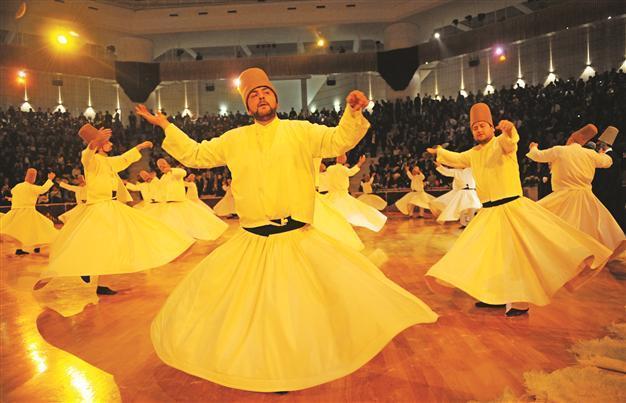

The importance of Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi is still such that people throughout the world celebrate his Dec. 17 wedding day (Şeb-i Arus), the day he died in Konya and was united with God – 740 years ago. The Mevlevis, as his followers are known, perform a unique whirling ritual (sema) which induces in its practitioners a trance-like state that brings them closer to unity with God.

The Mevlevis were one of a number of mystic sects that appeared following the rise of Islam in the seventh century. Scholars count 14 main sects. It is generally thought that they met some human need, not supplied by orthodox, government-regulated Islam, such as a wish for music and dance. Konya in the 13th century was the capital of the Rum Seljuks and a place of learning and the arts. It attracted many, including Mevlana’s father, especially as Genghis Khan and his army advanced toward Anatolia from Central Asia.

Mevlana’s message was one of “unlimited tolerance, positive reasoning, goodness, charity and awareness through love.” These sects most often took the name of the man who originally founded them, but in the case of the Mevlevis, the followers of Mevlana were only organized into a sect by his son after his death. From here the tradition that the head of the sect would be from Mevlana’s family in the male line has continued until today.

‘Come, come whoever you are’ Mevlana’s tolerance and goodness are best exemplified by his well-known lines: “Come, come whoever you are / An unbeliever, a fire-worshipper, come. / Our convent is not of desperation / Even if you have broken your vows a hundred times / Come, come again.”

Becoming a Mevlevi was not easy. The journey started in the kitchen of a tekke or lodge where the person who had announced his intention to join would serve a rigorous apprenticeship, known as the 1001-day apprenticeship that included lessons in Arabic in order to read the Quran and Persian to understand Mevlana’s works as well as performing menial tasks. When the elder members of the tekke deemed the apprentice was sufficiently prepared, they would vote to accept him in to the order. At that point he would start at the lowest rung of the ladder which would lead him to unity with God and then proceed through four stages. A member could only be cast out if he was found guilty of a moral offense.

Whirling ceremonies in tekkeThe tekke, usually made of wood, provided places for members to live and included bedrooms, dining rooms, kitchens, a ceremonial area and even a place where the women would live. The Mevlevis could and did marry and women could even become Mevlevis although they would perform their ceremonial whirling among themselves. The ceremonial ritual is held on a wooden floor constructed in an octagonal or round shape. A mimber (pulpit) occupied one side with the musicians seated directly opposite it. Observers could watch from a mezzanine, one side of which would be closed off with a wooden lattice so that women could watch the performers.

The whirling ceremony, which earned the sect’s members the sobriquet, Whirling Dervishes, is filled with symbolism. The late Professor Metin And, in a book he wrote with Professor Talat Halman on the dervishes, believed that it was mostly influenced by the shamanism of Central Asia. “The whirling itself symbolizes celestial motions; as the earth turns on its axis as well as revolving round the sun, so the dervishes pivot on their feet while making a revolution of the hall, which is considered the hall of celestial sound,” the book said.

“Mevlana said: ‘The sema is the soul’s adornment which helps it to discover love, to feel the shudder of the encounter, to take off the veils, and to be in the presence of God,’” And’s and Halman’s book said.

Halman explains how “opening the arms is the aspiration to spiritual excellence, the soul’s balance, union with God, and eternal bliss. The right arm points heavenward, to God; the left arm down to the earth.”

Mevlevi history The Mevlevis spread across Anatolia during the period between the decline of the Seljukid kingdom and the rise of the Ottomans in the 14th century. Although Fatih Sultan Mehmed conquered Istanbul in 1453 he forbade any mystic sect from operating in the city. The sects were only permitted to open tekkes in 1491-92. It was at that time the first Mevlevi tekke was opened at Tünel. From there Mevlevi tekkes spread to other places around the city such as Yenikapi and Beşiktas. These were located outside the city walls and near cemeteries and were surrounded by gardens. That was certainly the case with the Tünel tekke until the end of the 19th century when, thanks to the pressure of the foreign embassies and the Europeanization of the Beyoglu area, its land was considerably reduced in size.

Because the Mevlevi message was one of peace and tolerance, the sect was particularly popular with the Ottoman government. Many governmental officials, including grand viziers and possibly even one of the sultans were Mevlevi. At the same time, the Mevlevis were used against another sect, the Bektasis who were involved with the unruly Janissary corps.

In 1925, Turkish Parliament passed a law banning all mystic sects but not all of the tekkes were abandoned to their fate. The oldest existing tekke in Konya where Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi is buried was given museum status and much of the surrounding complex has been restored.

The next most important tekke at Tünel in Istanbul has been restored several times and is the only place where one can watch the whirling ceremony (sema) in an original setting. Unfortunately, only the main building remains of what was a large complex. The mausolea and graves of some of the most prominent Mevlevis such as that of Şeyh Galib who is the last great Ottoman poet still stand.

Although the mystic sects were banned, the Mevlevis were to some extent looked on with a benevolent eye. They could no longer perform their whirling ceremony in public, but it was widely known that they practiced it in private homes. Finally in the mid-1950s, permission was given for the sema to be performed in public for the first time but as a kind of touristic event. A group was finally permitted to travel abroad to give performances in 1973. Now they are a regular event all year round and this year the special performance in honor of Mevlana’s death (Şeb-i Arus) will be held in Istanbul for the first time.