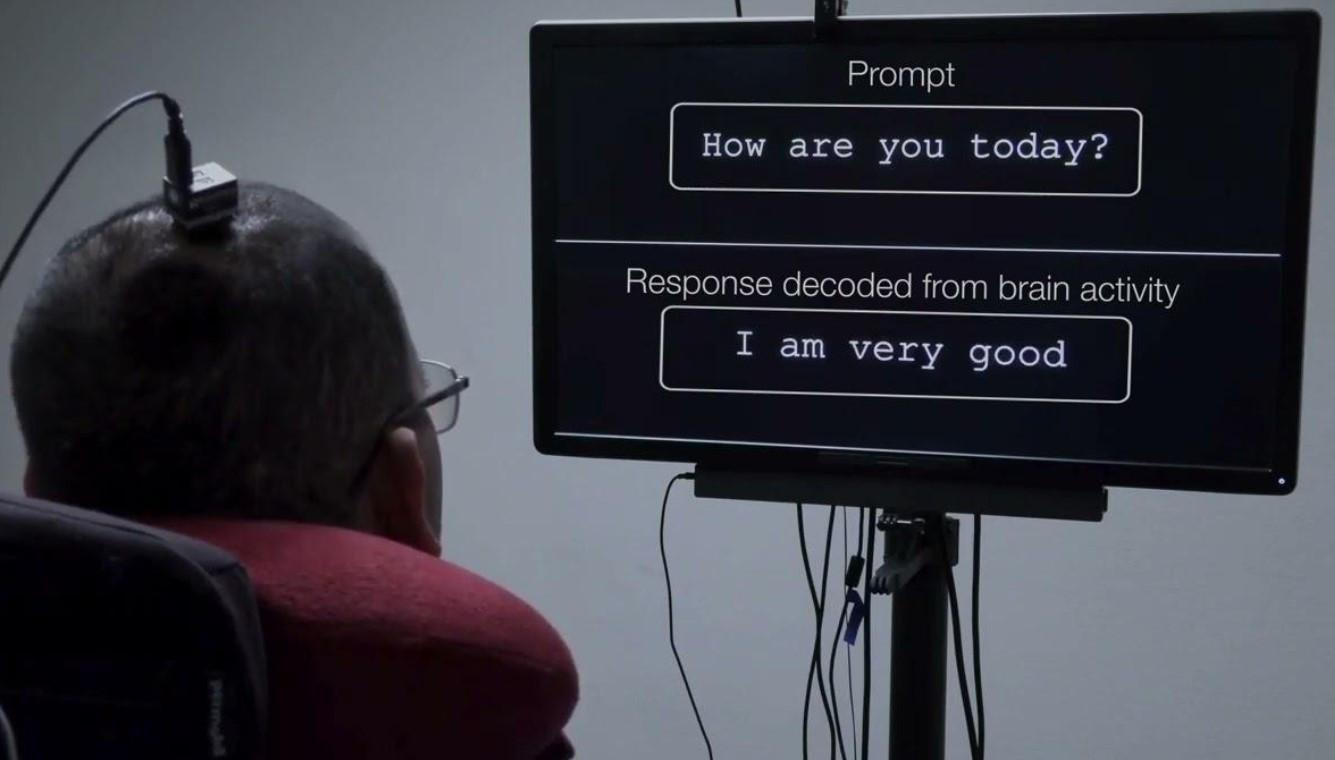

A paralyzed man who cannot speak or type was able to spell out over 1,000 words using a neuroprosthetic device that translates his brain waves into full sentences, U.S. researchers said on Nov. 8.

"Anything is possible," was one of the man's favorite phrases to spell out, said the first author of a new study on the research, Sean Metzger of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF).

Last year the team of UCSF researchers showed that a brain implant called a brain-computer interface could translate 50 very common words when the man attempted to say them in full.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Communications, they were able to decode him silently miming the 26 letters of the phonetic alphabet."

So if he was trying to say 'cat', he would say charlie-alpha-tango," Metzger told AFP.A spelling interface then used language-modelling to crunch the data in real time, working out possible words or errors.

The researchers were able to decode more than 1,150 words, which represent "over 85 percent of the content in natural English sentences", the study said.

They simulated that this vocabulary could be extended to more than 9,000 words, "which is basically the number of words most people use in a year," Metzger said.

The device decoded around 29 characters a minute, with an error rate of 6 percent. That worked out to be around seven words a minute.

The man is referred to as BRAVO1, as the first participant of the Brain-Computer Interface Restoration of Arm and Voice trial.

Now in his late 30s, he suffered a stroke when he was 20 that left him with anarthria, the inability to speak intelligibly, though his cognitive function remained intact.

He normally communicates by using a pointer attached to a baseball cap to poke at letters on a screen.

In 2019, the researchers surgically implanted a high-density electrode on the surface of his brain, over the speech motor cortex. Via a port embedded in his skull, they have since been able to monitor the different electrical patterns produced when he tries to say varying words or letters.

The research, which still needs to be confirmed in other participants, is still some way off from becoming available to the thousands of people who lose the ability to talk due to strokes, accidents or disease every year.