Blackened faces etched in our collective memory

Emrah GÜLER

‘The Mine’ tells the story of coal miners as they are led by a charismatic revolutionary into striking against the greedy mining companies and non-functioning unions.

It’s dirty, dangerous and the lowest of the low in an economic system that is far too brutal for many. The miners that have to go deep into the darkness every day for wages often show us the darker sides of the modern capitalist system. Last week left Turkey in mourning with the deadliest mining accident in its history. An accident that claimed the lives of at least 274 could have been prevented with the simplest measures as many are aware, despite the rants from government officials.The heartbreak is always multiplied when it hits closer to home. But there was something deeper for the people of Turkey in the heartbreak, the grief, and the subsequent anger in the aftermath of the recent mining disaster in the western town of Soma. The photos where the bright yellow helmets were juxtaposed against the tear-stained blackened faces or the faces of the relatives waiting in despair were too familiar.

The poor safety conditions of the mining industry that have become the norm for decades have cost some 3,000 lives since 1941. Many will remember the worst mining disaster, up until the Soma, the gas explosion of 1992 in the Black Sea port of Zonguldak that took the lives of 263 workers. Coal mines lead the toll as the deadliest, with 30 thousand dead since 1970.

The mine accidents are forever etched into our collective memory as one of the many tolls of living in this country, or as the prime minister and his accolades put it often so succinctly, “destiny.” Miners are respected, honored and romanticized in a different light in Turkey. That’s perhaps why it did not take much time after the news of the explosion to see many people recite in social media the famous lines by early 20th century poet Orhan Veli, “Yüz karası değil, kömür karası / Böyle kazanılır ekmek parası.” Though it is not much justice to the poem, but roughly translated as, “Not the black sheep, but the black of the coal / That’s how you earn your bread.”

‘You never saw the day, you never saw the light’

‘You never saw the day, you never saw the light’Other lines by famous and unknown poets alike followed suit. One user put Sunay Akın’s poem in white over black, “Another crack of coal in the stove. This time it was the heartbeat of a lost miner in the warm of the room.” Another recited Barış Erdoğan, “Don’t you worry about flowers blooming in black and bugs clamoring. Each corner of heaven is reserved for our miners.” Ümit Alphan’s The Black Grave was another poem shared many times, “Your hope, a pickax in your hand, a cigarette between your lips. You never saw the day. You never loved the sun.”

The audio and video recordings of the late rock singer, one of the pioneers of Anatolian rock and symbols of the left in the 1970s, Cem Karaca’s Maden Ocağı (The Pit) resurfaced, reminding sadly that not much had changed since its release in 1977. “There is no air, no light, down in the pit. There is no food, no appetite, down in the pit. Not even your son, down in the pit,” Karaca’s emotional rendition. The end of the song is heart-wrenching for many, more so last week: “They took you from this world. They took your light, you air, your food. The woman you love, the son you adored.”

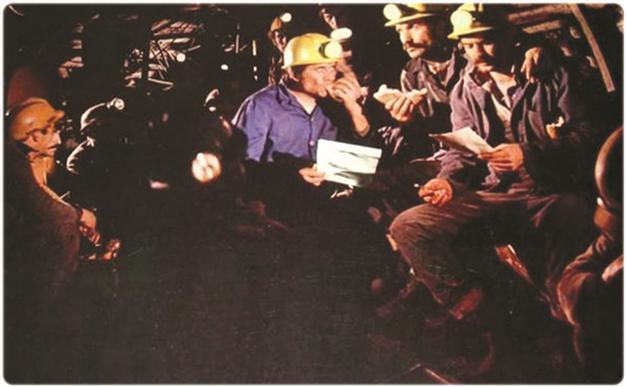

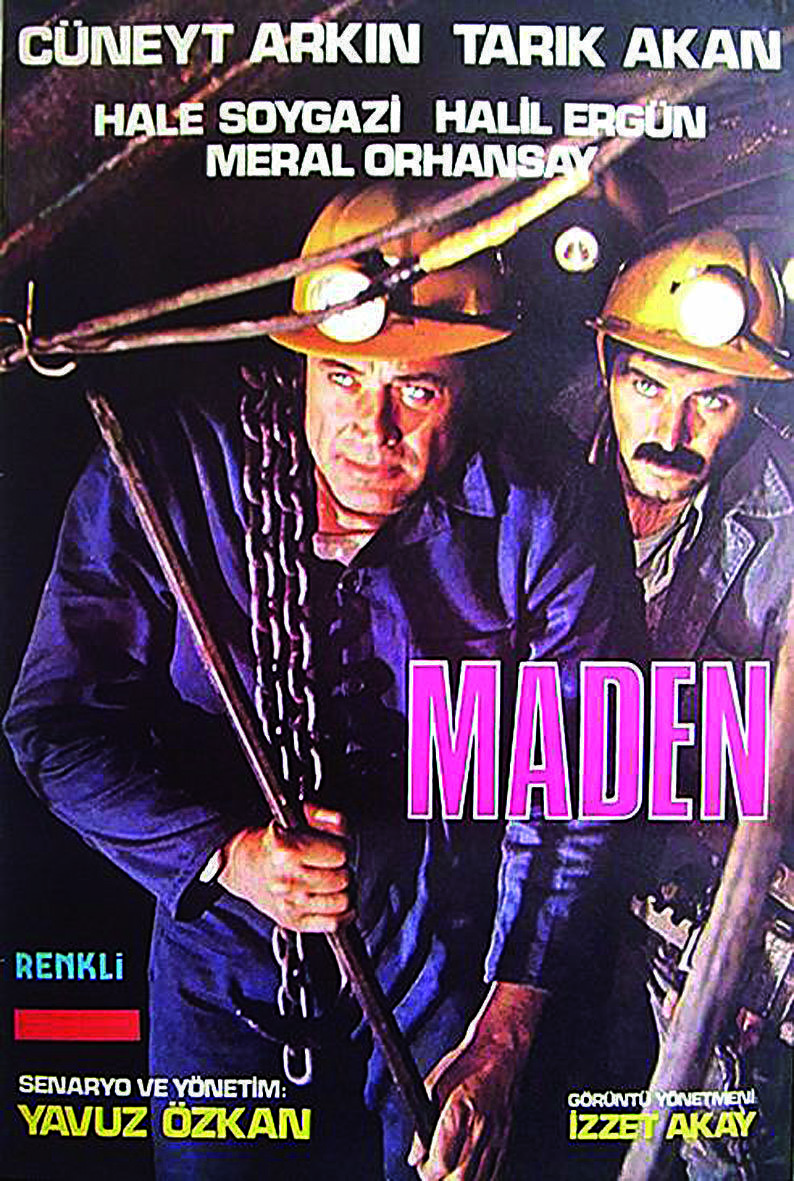

At around the same time Karaca wrote Maden Ocağı, the tragic lives of coal miners were being filmed for a feature by veteran filmmaker Yavuz Özkan. “Maden” (The Mine) of 1978, featuring the three stars of the time, Cüneyt Arkın, Tarık Akan and Hale Soygazi, tells the story of coal miners as they are led by a charismatic revolutionary into striking against the greedy mining companies and non-functioning unions. The collapse of a pit, distraction of the owner of the mining company by bringing the city an amusement park, a petition by and an assassination attempt on İlyas all take the workers toward a new awareness.

A climactic tragedy and a union come hand in hand, ending the movie with the hopeful message of “workers unite.” History repeating itself in many ways, the scenario for “Maden” was refused many times by a state commission on the grounds of “promoting discord, corrupting family life, and harmful to national customs and morals.” Eventually, the film won four Golden Orange awards, including Best Film. It’s hard not to have something in your throat for the people of Turkey to see these pieces from cultural history being as fresh and relevant decades later.