Bathonea excavations shed light on Istanbul’s history

ISTANBUL - Anadolu Agency

AA Photo

The Bathonea excavations that have been continuing in the Küçükçekmece lake basin for five years fill a gap in Istanbul’s chronology by revealing traces from 2,000 B.C.

The head of the excavations, Associate Professor Şengül Aydıngün said the first years were spent on cleaning, researching, mapping and geophysical work, while diggings started as of 2011-2012.

Aydıngün said the ancient ports and a lighthouse that were found during the first years proved that the region was a big port. “Walls, long roads to the sea, avenues and docks were found on the coasts,” she said.

Aydıngün said large structures, squares, churches and a palace complex became evident over time, and the excavation team had reached a large cistern on which names like Konstantin and Konstans were written. The cistern is believed to have dated back to the Byzantine era.

She said they were particularly excited when they found Hittite statuettes from as far back as 2,000 B.C., as well as ceramic pieces from the same period.

“With the early Hittite findings, we found contemporary Cypriot ceramics in small pieces. We now think Istanbul was livelier than we had thought back in the beginning of 2,000 B.C. We also see the traces of international maritime trade staring from this period. Further data will clarify this,” she said.

Aydıngün added that teams from universities in Germany, Britain, the Netherlands and Poland have joined the excavations so far, including architects, geologists, marine scientists, anthropologists and geophysicists, as well as archaeologists.

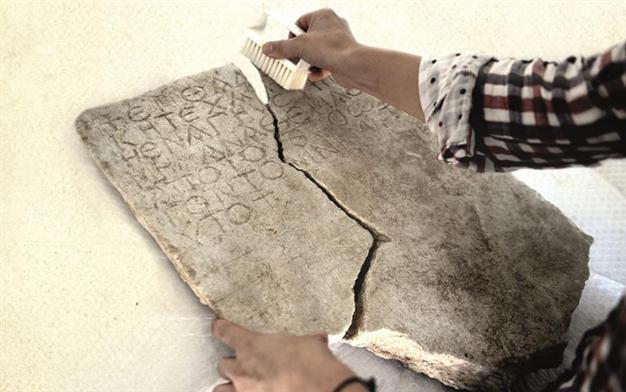

Thousands of pieces to be assembledThis year’s works at the site are focused on laboratory work, rather than in the excavations field. “We have worked on assembling unearthed pieces. Each piece of material is evaluated individually. It will continue until the end of the year. We have some 50,000 pieces of ceramics, waiting in boxes to be assembled. We have delivered a few thousand completed ceramics to the museum so far,” Aydıngün said.

“Thanks to the pieces we found during excavations, we started filling the gaps in Istanbul’s historical chronology. We previously learned about the city’s Neolithic age in excavations at Yenikapı, Fikirtepe and Pendik. We knew about 6,000 B.C., but we did not have an interim period. We did not know about the Istanbul of the Hittite era or early Bronze Age. These excavations shed light on this era, and are exciting for the scientific world,” she said.

“We have excavated level by level. Each level gives us different information on each era. The information will become more serious in the next levels ... The Ephesus, Bergama, Troy and Alacahöyük excavations lasted 100 years and the Kültepe excavations took 60 years. This place will take even longer; it will take a few more generations, but my students will continue digging,” Aydıngün said.

She added that underwater work could not be conducted because the Küçükçekmece Lake was too dirty. “About 90 percent of the water is filled with sewage, nuclear and industrial waste. It is difficult to see [in the lake], so our underwater team could not work. Maybe there is a sunken ship like in Yenikapı, because we have found many broken pieces on the shore. There are also ceramic pieces from the Roman era, suggesting that maritime trade took place. When the lake is cleaned properly, we will be able to know more,” Aydıngün said.