Armstrong legacy: Dope and inspiration

WASHINGTON - Agence France-Presse

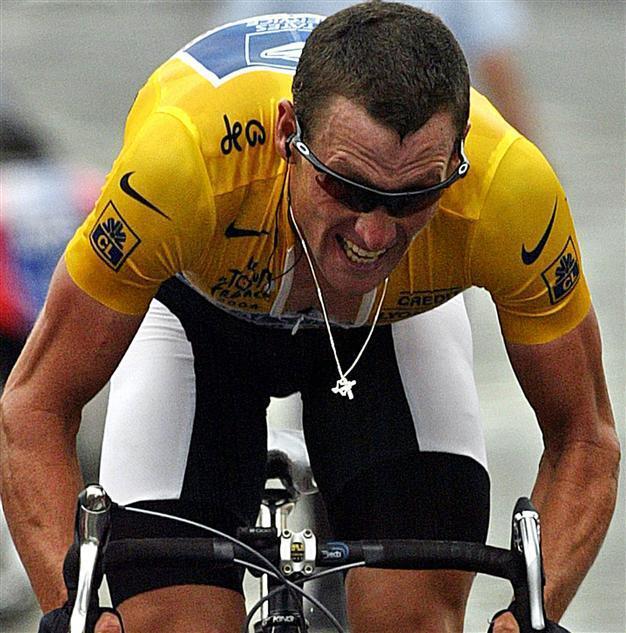

Armstrong, who won his Tour de France races after cancer, has been an inspration to other cancer conquerors. AFP photo

Lance Armstrong was scorned last week as a dope cheat whose seven Tour de France cycling triumphs are forever tainted.

Next weekend, he will be hailed in his Texas hometown as an inspiration to people fighting cancer, his victories a symbol of how cancer can be overcome.

And there’s plenty of evidence to support both portraits of the 41-year-old American, the yin and yang of a man who has proclaimed his innocence even as former teammates have tarnished their own reputations to testify against him.

The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency unveiled its report to the International Cycling Union (UCI) on why it banned Armstrong for life in August and stripped him of his Tour de France titles, which the UCI could yet challenge.

The move came after Armstrong decided not to fight USADA charges in an arbitration hearing, having lost a U.S. federal court fight objecting to the system in which athletes can appeal the accusations.

Among 202 pages of findings and much more evidence outlined by USADA was testimony from 26 people, including 11 former Armstrong teammates. Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis were already admitted dope cheats but USADA issued six-month bans to George Hincapie, Tom Danielson, Levi Leipheimer, David Zabriskie and Christian Vande Velde based on their testimony.

Armstrong has maintained his innocence yet is unwilling to challenge the evidence against him in a hearing and face his accusers.

Fight against cancerBut for all the sporting accusations, Armstrong will celebrate next weekend the 15th anniversary of his charity foundation, which has evolved into the cancer-fighting Livestrong Foundation.

“We believe that unity is strength, knowledge is power and attitude is everything,” Livestrong says on its website. “Our leaders and donors provide vision and support for our mission.”

While Armstrong’s former teammates were united in naming him a dope cheat and the accusations rocked his image, he has sought to put the matter behind him and pursue his efforts to inspire others to fight cancer.

Donations to Livestrong have totaled almost $500 million since 1997 and the money has funded life-changing programs to help people with cancer.

Armstrong is set to appear at a Livestrong gala next weekend in Austin, Texas, together with a Livestrong cycling event where the aim is to have 4,000 cyclists participate and raise $2 million.

Armstrong, who won his Tour de France races after surviving testicular cancer, has been a role model to inspire other cancer conquerors over the years, encourage those who fight the condition to this day and give families hope.

The Austin American-Statesman newspaper hailed Armstrong as a “person to be deeply admired” for his cancer-fighting efforts. “The trickier legacy is the one that goes beyond cycling. If admirable work turns out to be built on a lie, is the lie then OK, the cheating excusable?” it added in an editorial.

Armstrong’s inspirational role has taken prominence to an American sporting public weary from doping revelations from numerous athletics stars and unproven accusations against baseball icons such as Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens.

The American-Statesman dismissed as an “absurd proposition” to pretend that Armstrong never won the Tour de France.

“It’ll be an acute absurdity to those countless Americans who, inspired by Armstrong’s wins, got off their couches and onto a bike,” the newspaper added.

Ex-WADA head suggests UCI turned blind eye to Armstrong

LOS ANGELES – Agence France-Presse

The International Cycling Union (UCI) likely turned a blind eye to alleged doping by Lance Armstrong and others, the former president of the World Anti-Doping Agency has suggested.

Richard Pound said he complained for years to the UCI that the seven-time Tour de France winner and other cyclists were given advance notice of their drug tests and then allowed to go off unsupervised.

“It is not credible that they didn’t know this was going on,” Pound told AFP in an interview. “I had been complaining to UCI for years.” Pound, who was head of WADA from 1999-2007, said drug testers would do tests on riders in the early-morning, hours before they had to appear for a competition.

“The race starts at 1 pm to 2 pm in afternoon and there are no tests prior to race to see if they are bumped up,” he said, adding that after races, competitors had an unchaperoned hour before being tested.

“So then you go in and get saline solutions and other means of hiding the effects (of performance-enhancing drug) EPO and whatever else it is,” he said.

“You have to say ‘I wonder if it was designed not to be successful?’”