Arkas Arts Center displays testimonials of Anatolian antiquity

Nazlan Ertan - İZMİR

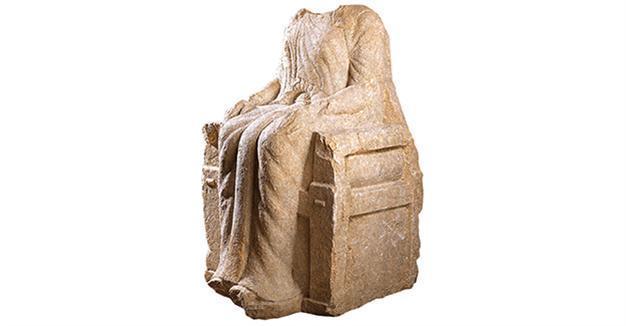

There is a smallish woman dressed in a cloak draped across her right shoulder, sitting in a massive chair. The fact that she has her hands resting on her thighs and her feet in a footstool, as well as the elaborate pleats in her clothing, indicate that she is a sacred person or holds a sacred office. She seems to be intentionally mutilated: the head is missing and the hands have been partially torn off.

The statue is one of the most interesting items that make up the “Testimonies of the Anatolian Antiquity,” a collection of 300 historical objects and 500 coins brought together in İzmir’s Arkas Art Center. The collection is part of approximately 2,000 coins and 1,315 historical objects belonging to İzmir-born businessman Muharrem Kayhan. The “Seated Woman” is believed to be from the archaic period in Miletus and Yeniköy, made around 540 B.C. According to Jean-Luc Measo, the curator of the exhibition, it is one of the statues that decorated the sacred way from Miletus to the Temple of Apollo at Didyma.

The statue was an anniversary gift from Kayhan’s wife, Berna. Other items, such as coins, terracotta, bronze, marble and glass objects, are the result of his passion, his slow and deliberate acquisition both in Turkey and abroad since the mid-1980s. The display also includes 45 coins from the collection of his brother, Hilmi.

It is easy to succumb to the cliché that a collection almost infallibly reflects the collector himself. Kayhan’s own background and the geography he lives in rings very close to the focus of the collection, which is made up of coins and other objects from Caria (the region that extends from the south of Menderes river to the north of the Muğla province in southwestern Anatolia) and Ionia (which covers modern day İzmir and Aydın on the Aegean coast) during the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic eras.

“Day in and day out, I treaded on the path of history on my way from home to work and work to home,” Kayhan told Hürriyet Daily News on the telephone. Kayhan Family owns Söktaş textiles, a forty-five-year-old company based in Aydın. “It would have been unusual not to be curious about where I live. I am very happy that the coins in particular have returned to the lands of their birth.”

His interest started with historical objects in the 1980s but quickly turned into coinage because coins, with their rich history, gave him the opportunity to expand his knowledge and provide hints on how the ancestors of his native land lived. “A collector without in-depth knowledge of what he collects is just a hoarder,” he added.

The long path to exhibition

“The Testimonies of Anatolian Antiquity,” the first and possibly only display of Kayhan’s vast personal collection, opened to the public through his friendship with Lucien Arkas, the chairman of Arkas Holding. “Lucien Arkas knew of my collection and wanted to exhibit it. It took us 1.5 years to choose, classify and set up what we want to display,” Kayhan said.

“The objects and the coins are organized in a thematic framework, rather than a linear chronology,” explains Müjde Unustası, the director of the exhibition. “Archaic era... cult objects, gods and goddesses, the house, women and animals are the main themes of the exhibition, presenting the life in antiquity through coins and other objects.”

This is, indeed, a multidimensional life, with rituals for table, for feasts, for work, marriage and for burials. Delicate glass, soft curves on marble, delicate statuettes of animals and deities find their place in the Arkas hall, united in the diversity of the different civilizations they represent.

“The Archaic to the Byzantine periods are characterized by the combination of ethnic, religious, linguistic and economic identities, all marked by local traditions, the Greek civilization, Roman contributions, and the pre-Hellenic heritage,” says Maeso, the exhibition’s curator. “The story told by the objects here is a vast chronology of the coming-together of populations and lands, bound by exchanges and influences, a rich history and dramatic upheavals. It is a living legacy which reveals the customs, ways of life, funerary ceremonies and the urban and agrarian life.”

Coins: power, protection and passion

Coins occupy a particular place in the exhibition – not only because they are the main interest of the collector but because of the great displays that make them not only informative but fun to look at.

“Those coins from antiquity are works of art and historical evidence – two qualities which I hope will be revealed to the visitor,” says Kayhan.

They clearly do. To the smallest coins that are no more than small punched ingots to the larger Miletus coins with the symbol of the bee, they tell a complicated story of what our ancestors believed to be sacred. Then they became money as a source of power and legitimacy, with the detailed portrait or profile of the ruler carefully chiseled. “Rulers used their symbol, but not their face before Alexander,” said Kayhan. “It was after Alexander that the images of the rulers appeared on the coin.”

In the room devoted to the Hacetomnid Dynasty, the profile of Apollo can be seen on the coins issued by the rulers in the fourth century B.C. They wore a double hat, like the official governors of the Persian Empire and hereditary Karian dynasts who had to push for their own interests against those of the Persians. In many ways, not least by their coinage, they were the forerunners of the Hellenistic kings.

“I have decided to end my coin collection this exhibition,” says Kayhan. “What is missing in the collection from these lands and periods is both very rare, if not inaccessible.”

A youthful glance at heritage

As I tour the exhibition before my interview with Kayhan, a group of school children around eight years old rush in. Despite the orderly way they enter, it is clear that they are more interested in the grave and the objects around it, the main feature in the large hall. Some focus on the lion sculptures, another asks immediately to be shown the animals, possibly referring to the small ornaments of bulls, stags and dogs from the Roman period on the second floor.

Kayhan is passionate about museums, which themselves are centers of attraction through their architecture, enabling the next generation to become more aware of their heritage. “Schools and parents have a role to play there. Cinema and popcorn can only take you so far,” he says.

There is a smallish woman dressed in a cloak draped across her right shoulder, sitting in a massive chair. The fact that she has her hands resting on her thighs and her feet in a footstool, as well as the elaborate pleats in her clothing, indicate that she is a sacred person or holds a sacred office. She seems to be intentionally mutilated: the head is missing and the hands have been partially torn off.

There is a smallish woman dressed in a cloak draped across her right shoulder, sitting in a massive chair. The fact that she has her hands resting on her thighs and her feet in a footstool, as well as the elaborate pleats in her clothing, indicate that she is a sacred person or holds a sacred office. She seems to be intentionally mutilated: the head is missing and the hands have been partially torn off.