Ara Güler’s ‘Anatolia’ captures a disappearing past

Hilal İşler WASHINGTON

The photographs are all taken in the 1960s and include important Anatolian sites as the Nemrut Mountains.

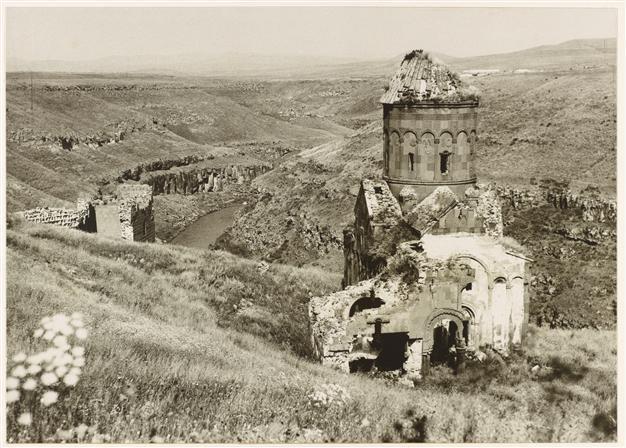

Ara Güler is known as one of Turkey’s most prominent photojournalists and since Dec. 21 of last year, his never-before-seen works have been on display at the Smithsonian, in Washington D.C. “In Focus: Ara Güler’s Anatolia” looks at Seljuk, Armenian, and Ottoman monuments of the Turkish heartland through Güler’s lens. It draws to a close on July 20.The photographs, all taken in the 1960s, consider Turkey beyond the boundaries of Istanbul. In them, Güler looks east to the forgotten, dusty corners of Anatolia; its abandoned churches, and mosques in disrepair. It’s an area that has long held the photographer’s interest.

“Ara Güler started his photojournalism career in the early 1950s in local Turkish newspapers,” explains Zeynep Simavi, who helped curate the exhibit. “He’s mostly known for his photographs of Istanbul, and for his artist-portraits. But even in the 50s and 60s he was traveling extensively throughout Anatolia and photographing these monuments. In fact, he has said that he thinks his most important contributions are things like photographs of the Nemrut Mountain, or his ‘rediscovery’ of Aphrodisias.”

Simavi says close to 115,000 people have visited the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery during the Güler show, which is now enjoying an extended run. The exhibition was originally scheduled to end in May.

Simavi says close to 115,000 people have visited the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery during the Güler show, which is now enjoying an extended run. The exhibition was originally scheduled to end in May. “Many people who visit and who haven’t heard of Güler are surprised and inspired by the works that he has taken here,” says Allison Peck, a Smithsonian official. “A lot of people in the Turkish and Turkish American communities especially are hearing about the show and making a special effort to visit.”

Güler’s body of work is said to include over 800,000 photographs. The 21 that constitute “In Focus” were gifted to the Smithsonian by Raymond Hare, a former American Ambassador to Turkey. The photographs honor Hare’s interest in Turkish architecture, and were given to him by colleagues as he prepared, in 1965, to leave his Ankara-post.

In addition to the black-and-white images, “In Focus” includes the short documentary, “Ara Güler: A Lifetime Achievement.” The video plays on loop, and features Güler’s own thoughts on his career. “I’m a Turkish photographer,” Güler says in the film, speaking in French. “Actually, I’m a press photographer. Photography being a visual medium, we press photographers to record the visual history of time. I find that more crucial than creating art, for humanity learns from its history.”

Güler identifies strongly as a photojournalist, but the exhibit encourages visitors to question this and to ask whether his work is, in fact, art.

“He has said many times, ‘I’m not a photographer, I’m a photojournalist. It’s one of the distinctions he makes,” says Simavi. “I think he places a lot of emphasis, and a lot of importance, on that aspect of his work. There’s this duty, this responsibility he feels to carry a message. It’s a social responsibility, to tell the public what’s going on. He’s there, witnessing an event for them. I think he very much believes in the objective value of what he is doing. He’s not manipulating events. He doesn’t have any control over them. He’s just there as an eye. He’s been doing that all his life. So, there’s a larger purpose to his photographs, always.”

Güler, who turns 86 next month, was a student of economics at Istanbul University when he accepted his first photojournalism assignment. He would later become head of photography at the now-defunct Hayat magazine, and would go on to publish internationally for Paris Match, Time, Life, and Stern magazines, among others. Today, he continues to work in Istanbul, and, earlier this month, received an honorary doctorate at Boğaziçi University.

For more on the exhibit, visit the Smithsonian online.