French author Annie Ernaux won this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature on Oct. 6 for blending fiction and autobiography in books that fearlessly mine her experiences as a working-class woman to explore life in France since the 1940s.

In more than 20 books published over five decades, Ernaux has probed deeply personal experiences and feelings - love, sex, abortion, shame - within a society split by gender and class divisions.

After a half-century of defending feminist ideals, Ernaux said “it doesn’t seem to me that women have become equal in freedom, in power,” and she strongly defended women’s rights to abortion and contraception.

“I will fight to my last breath so that women can choose to be a mother, or not to be. It’s a fundamental right,” she said at a news conference in Paris. Ernaux’s first book, “Cleaned Out,” was about her own illegal abortion before it was legalized in France.

The prize-giving Swedish Academy said Ernaux, 82, was recognized for “the courage and clinical acuity” of books rooted in her small-town background in the Normandy region of northwest France.

Anders Olsson, chairman of the Nobel literature committee, said Ernaux is “not afraid to confront the hard truths.”

“She writes about things that no one else writes about, for instance her abortion, her jealousy, her experiences as an abandoned lover and so forth. I mean, really hard experiences,” he told The Associated Press after the award announcement in Stockholm. “And she gives words for these experiences that are very simple and striking. They are short books, but they are really moving.”

French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted: “Annie Ernaux has been writing for 50 years the novel of the collective and intimate memory of our country. Her voice is that of women’s freedom, and the century’s forgotten ones.”

While Macron praised Ernaux for her Nobel, she has been unsparing with him. A supporter of left-wing causes for social justice, she has poured scorn on Macron’s background in banking and said his first term as president failed to advance the cause of French women.

Ernaux’s books present uncompromising portraits of life’s most intimate moments, including sexual encounters, illness and the deaths of her parents. Olsson said Ernaux’s work was often “written in plain language, scraped clean.” He said she had used the term “an ethnologist of herself” rather than a writer of fiction.

Dan Simon, Ernaux’s longtime American publisher at Seven Stories Press, said that in the early years, “she insisted that we not categorize her books at all. She did not allow us to refer to them as fiction and she did not allow us to refer to them as nonfiction.”

Ultimately, he said, Ernaux has created “a genre of fiction in which nothing is made up.”

“She’s a great storyteller of her own life,” Simon said.

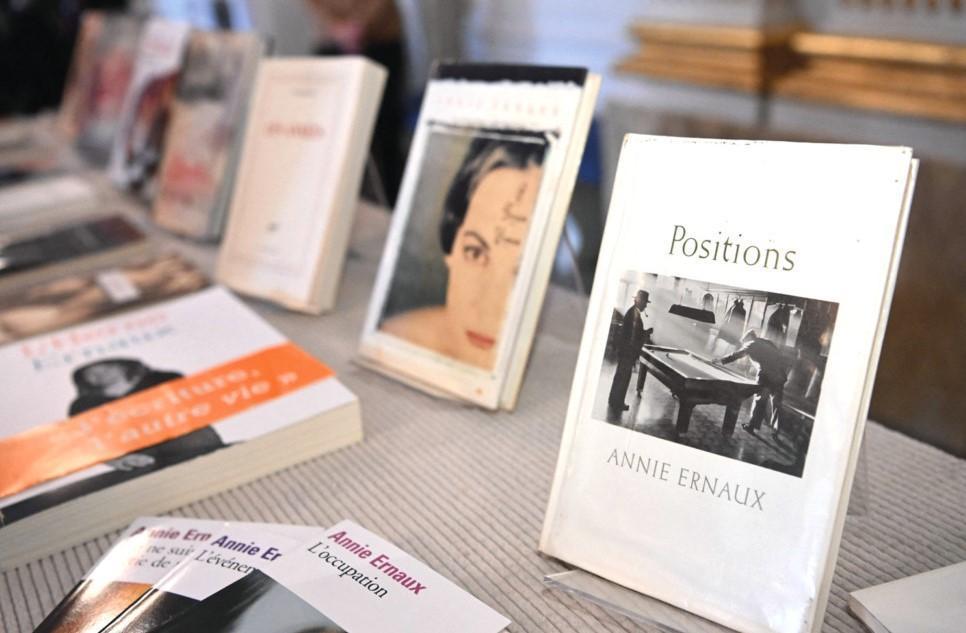

Ernaux worked as a teacher before becoming a full-time writer. Her first book was “Les armoires vides” in 1974 (published in English as “Cleaned Out”). Two more autobiographical novels followed - “Ce qu’ils disent ou rien” (“What They Say Goes”) and “La femme gelee” (“The Frozen Woman”) - before she moved to more overtly autobiographical books.

In the book that made her name, “La place” (“A Man’s Place”), published in 1983 and about her relationship with her father, she wrote: “No lyrical reminiscences, no triumphant displays of irony. This neutral writing style comes to me naturally.”

“La honte” (“Shame”), published in 1997, explored a childhood trauma, while “L’evenement” (“Happening”), from 2000, dealt like “Cleaned Out” with an illegal abortion. Her most critically acclaimed book is “Les annees” (“The Years”), published in 2008. Described by Olsson as “the first collective autobiography,” it depicted Ernaux herself and wider French society from the end of World War II to the 21st century. Its English translation was a finalist for the International Booker Prize in 2019.

Ernaux’s “Memoire de fille” (“A Girl’s Story”), from 2016, follows a young woman’s coming of age in the 1950s, while “Passion Simple” (“Simple Passion”) and “Se perdre” (“Getting Lost”) chart Ernaux’s intense affair with a Russian diplomat.

Ernaux has described facing scorn from France’s literary establishment because she is a woman from a working-class background.

“My work is political,” she said at the news conference. She described growing up in a milieu outside the elite, a world of “people above you” and the seeming impossibility of becoming a famous writer.

The literature prize has long faced criticism that it is too focused on European and North American writers, as well as too male-dominated. Last year’s prize winner, Tanzanian-born, U.K.-based writer Abdulrazak Gurnah, was only the sixth Nobel literature laureate born in Africa.

More than a dozen French writers have captured the literature prize, though Ernaux is the first French woman to win, and just the 17th woman among the 119 Nobel literature laureates.