Princely doodling in the 15th century

NIKI GAMM

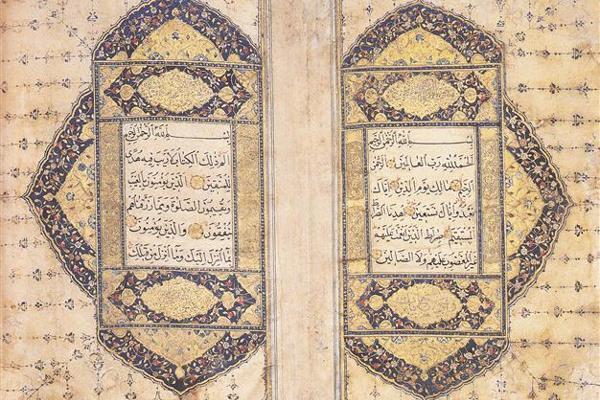

Quran by Şehzade (Prince) Korkut, late 15th century. Sakıp Sabancı Collection.

Doodling has been around for centuries, maybe millennia; at its simplest, it is defined as sketching aimlessly or mindlessly. In spite of this “art” form, there does not seem to be an equivalent word in Turkish, just a definition. So that is why people were astonished when several doodles were released to the public in Turkey in the mid-20th century as the work of Prince Mehmed (1432-1481), the son of Sultan Murad II who later replaced his father on the throne and became known as Fatih Sultan Mehmed.

Prince Mehmed with his father Sultan Murad II.

The subjects are varied, although the ones that first catch the eye are the sketches of men’s heads. They include Muslim and non-Muslim men, but no women. Each is an individual – one with a beard and turban, a second with a cap, another with ears that stick out and so on. No one knows who these men were, although there is some speculation that some of them were the foreigners at court.

The Perso-Arabic Ottoman script and the Greek alphabet are reproduced as if the writer were intending to practice them or had written them down in order to show off his mastery. Fatih Sultan Mehmed is known to have spoken Turkish and Greek and had a thorough grounding in Latin, Hebrew, as well as an understanding of Slavic languages. There are several attempts at producing an imperial signature, that of his father’s and of his own. The flowers and flower motifs are similar to the flowers and floral arrangements that were popular during the mid-15th century. One can identify a carnation and the kinds of leaves that were known as “hancer” (sword) leaves because of their sharp points. Animals and birds are realistically drawn, so much so that we can identify horses, storks, owls and eagles. One horse head even has its halter on. A few poetic couplets in Persian were included.

Mehmed was particularly known to be very high-strung and rebellious about being schooled. The drawings in the notebook are just the kind one might expect to find a bored schoolboy doing today.

A.Süheyl Ünver

Enter one of Turkey’s great scholars of the modern era, A. Süheyl Ünver, who was born on a day in February (1898) and died on a day in February (1986). In western terms, he was a person known as a renaissance man – someone with a wide range of abilities and talents who made use of them. Ünver was a doctor, historian, researcher, academic, calligrapher and writer. His works are still held in high regard today and are frequently quoted. He was one of the founders of the Turkish Language Society and the Turkish Historical Society.

In 1453, the Journal of Istanbul’s Culture and Art, Yaşar İliksiz relates how Ünver first ran across the notebook in the 1940s, but did not publish his opinion about it until 1956 because the evidence for its origin could not be substantiated. However, on very careful examination of the manuscript he did and his claim was first met with skepticism. Later on, the notebook was accepted as authentic when it was shown that the watermarks on the paper could be directly traced to paper used for deed records dating to 1431-1437 and for other estate registries about 30 years later.

Images of faces drawn by Fatih Sultan Mehmed.

In 1953, even though Ünver had not published Mehmed’s notebook, he prepared a number of notebooks on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul and made them in an artistic fashion with watercolors. The most important of these notebooks was “Fatih’in Defteri” (Fatih’s Notebook), which has now been published by IBB Kültür A.Ş. in a way that is faithful to the original characteristics. Professor İsmail Kara prepared the publication and Ünver’s daughter, Gülbün Mesara assisted with explanations of the miniatures. This “new” notebook, in a boxed edition, is 50-pages-long in honor of the 49 years of Fatih Sultan Mehmed’s life, plus one extra.

The pages have been prepared as if they were pages in a 15th century manuscript with decorations on the edges and corners and a blank square or rectangle in the middle, as one can see from the examples offered. The miniatures include three portraits of Fatih, three examples of Fatih’s signatures, his mother Hadice Hüma Hatun, his father Sultan Murad II, his teacher and the scholars who were around him. In addition, there are drawings of a number of buildings that were extant during his lifetime or he himself built, such as Fatih Mosque, Topkapı Palace’s Treasury Room, the Çinili Köşk, the Old Palace and Rumeli Hisarı. Ünver deliberately left some pages blank in order for people who were perusing it to rest their eyes.

This 20th century scholar prepared a book, as if it were being made in the 15th century. Ünver wrote in Milliyet in 1953, “The pleasure of that era was very refined, very diverse and quite rich. But we are living in the 20th century, five centuries later. In our century, our spirit doesn’t tire us out and it has been decided that we should enjoy simplicity. Consequently, these [notebooks] are few in number, correct and plain.

“This, in the end, is a notebook. Its being published in detail wasn’t even considered. At this point, it completely has a private character. So we haven’t gotten used to giving attention to dwelling on such serious subjects. The nobleness and virginity that we wanted to give to this notebook by this means will remain guarded for now. We have never made additions to the embellishment by ourselves. We almost always took authentic examples from that period – the miniatures likewise. We never went beyond them. However, we always gave room to details that included time and places. We took examples of painting techniques between the 16th and 19th century as the basis for the scenes and buildings of that period when we couldn’t find examples that remained from the period. And we drew in the international documentary work style of the 19th century what was meaningful in a number of places from that period.”

Fatih’in Defteri is available at the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality’s bookstores.

================ =

PHOTOS

Defter1- Images of faces drawn by Fatih Sultan Mehmed.

Defter2- Floral designs drawn by Fatih Sultan Mehmed.

Defter3- Poems by Şeyh Hamdüllah in the 15th or early 16th century. Sakıp Sabancı Collection.

Defter4- Quran by Şehzade (Prince) Korkut, late 15th century. Sakıp Sabancı Collection.

Defter5- The newly released box edition of Süheyl Ünver’s Fatih’in Defteri.

Defter6- A page from S. Ünver’s book, Fatih’in Defteri.

Defter7-