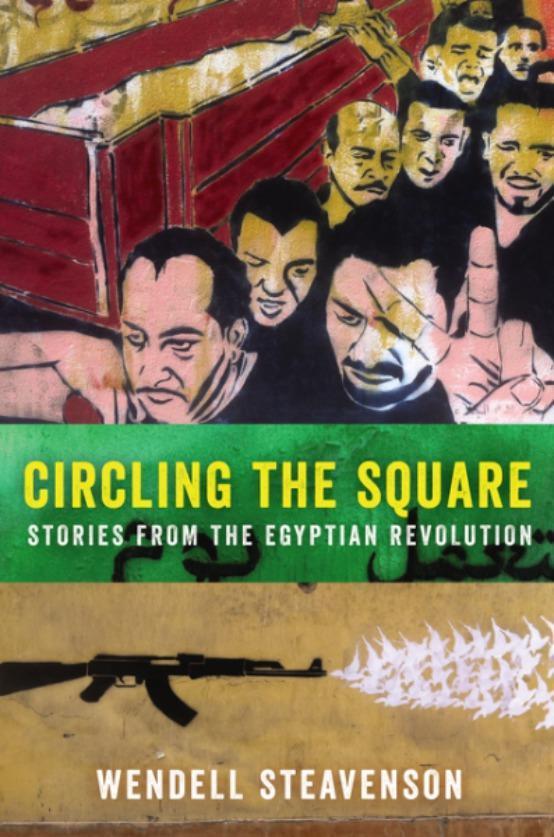

Stories from the Egyptian revolution

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

The fifth anniversary of the Egyptian uprising in January passed almost without notice internationally. The paranoid Sisi regime cracked down on any potential unrest at home, while attention abroad was focused on conflagrations elsewhere in the Middle East. The optimistic story of the Arab Spring has long since deteriorated to a grim landscape of proxy wars and sectarian conflict.

Its author recognizes this herself. Many chapters are fragmentary, full of cut frames and scenes. Steavenson returns impulsively to Tahrir Square, the cradle of protest and Egypt’s political barometer for two tumultuous years: Through the first demonstrations against Mubarak in January 2011, the pandemonium in the months after he fell, and the turbulent experiment in democracy that ended with the military coup against Mohamed Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood-backed government in July 2013.

Steavenson admits to feeling doubt, insecurity and often sheer incomprehension. “During the many occasions I was present during fighting, riots, rock throwing, I began to realize that witnessing something did not give you any good sense of what had really happened. In fact it was the opposite,” she writes. “In the midst of the fray … you were blinded by tear gas or running away. The scene was jumbled … The more I went to protests the less I could see. A person bearing witness was the most unreliable narrator of all.”

She describes the period as a “giant sprawling messy epic,” unplanned and subject to many plot twists. The pages are filled with a diverse cast of characters, with Steavenson aware of the temptation to be beguiled by the hip, young, tech-savvy (and unrepresentative) revolutionaries. She meets plenty of those, but she also speaks to many people from the “couch party” of apolitical Egyptian masses derided by Tahrir protesters. Conspiracy theories flourish on all sides and many of them will be grimly familiar to readers in Turkey. A general on Tahrir Square derides the crowd as foreign agents “who want to destabilize Egypt.” A lieutenant colonel similarly assumes they are paid for, suspicious of the KFC-eating revolutionaries and saying “I want to know where all this stuff is coming from, where the money is coming from.”

The Brotherhood is a lingering presence throughout the book. It remained cautious during the anti-Mubarak protests, but as the best organized political group it was able to benefit from the first free elections after he fell. Many revolutionaries saw the Brotherhood’s “exploitation” of the revolution as an opportunistic betrayal and many cheered from the sidelines when the army toppled Morsi.

“Circling the Square” does not attempt deep historical analysis, but Steavenson is astute on a number of broader points. In one section she uses an uneasy visit to Cairo’s Heliopolis neighborhood, citadel of Egypt’s military-industrial complex, to describe the vast network of individuals, institutions, private and state interests dependent on the military for their wellbeing. “In Egypt the army was the engine room, ballast, star chamber, puppeteer. The army was all these things and a hundred more no one understood,” Steavenson writes,

It was also a vast corporation and a giant welfare umbrella. Every Egyptian eldest son with a male sibling was conscripted for three years of military service, but despite the numbers of Egyptians who went through its procedures, the Egyptian army was opaque. Its budget was secret, its business interests undisclosed. It was against the law to mention the army in a newspaper or talk about it on television ... Egypt had been under emergency law for thirty years. This emergency law was not rescinded after Mubarak fell. All the public land in Egypt was by default owned by the army.

In what is now a familiar story from unrest elsewhere, the protests’ lack of leadership or shared goals – originally a strength – became a weakness after Mubarak fell. As the strongest, most rooted, most authoritative institution in the country, the military was well-placed to reassert itself amid the chaos of the revolution and Morsi’s years in power.

“Circling the Square” comes to an ominous conclusion with its account of the army’s massacre of hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters at Cairo’s Rabaa Square on Aug. 13, 2013. That bloody episode marked a definitive full-stop to the revolutionary cycle and heralded an era of fierce repression, probably worse than anything under Mubarak. Of course, we know all this as we read the book. That means it is often a very sad read: A tale of how a country’s mood can swing so quickly from chaotic optimism to bitter pessimism. Today most foreign correspondents like Steavenson have left Egypt amid the impossibility of doing proper work in such an atmosphere. Among many other things, the Egyptian example since 2011 is a cautionary one for Turkey today.

*Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here.