'In Jail with Nazım Hikmet'

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

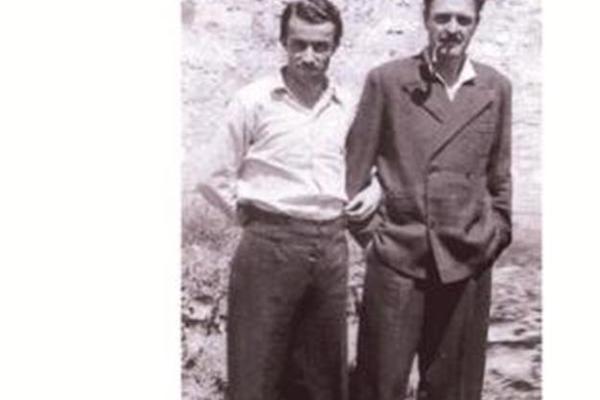

When Nazım Hikmet was transferred to Bursa Prison in the winter of 1940, his reputation went before him. He wasn’t yet known by the inmates as Turkey’s greatest 20th century poet, but he was already a legend, the kind of man loved even by his enemies. On seeing him arrive with his few modest belongings, the future novelist Orhan Kemal, who was mid-way through his own five-year jail term on similar charges of communist sedition, marvels that the great man “could have a mattress, a suitcase, a basket ... But he must be a ‘super-human’ being, a genius.” Unsent letters addressed to Hikmet were among the possessions that had landed the young Kemal in prison, but while there he went from being a distant hero-worshipper to a close friend and intellectual confidant. This memoir is a lovely, tender account of the three years they shared a cell - both a valuable source on Hikmet’s time in Bursa Prison and an inadvertent account of Kemal’s own artistic coming of age. In fact, it surpasses many of Kemal’s own (often underwhelming) novels.

The recent biography of Hikmet by Mutlu Konuk Blasing reflected on the uncomfortable fact that it was perhaps his time inside that made him the great poet he became. His 12 years of imprisonment were by no means easy, but he was still extraordinarily industrious. He wrote incessantly, translated Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” into Turkish, taught countless fellow inmates to read and write, set up an active and very productive weaving workshop, followed every shift of fortune during World War II, acted as an artistic mentor for the likes of Kemal, and compiled his magnum opus, “Human Landscapes from My Country.” Kemal’s memoir gives a glimpse of all those endeavors.

The novelist was still only in his 20s when Hikmet arrived at his prison, and had the rare luck to be taken under the wing of his idol, who vowed to help him achieve his full artistic potential. Hikmet is quoted as telling the school-leaver Kemal that he’d “like to take [him] in hand … for [his] education,” and this is exactly what happens. Upon his advice, Kemal abandoned the mannered, syllabic poems that he had been writing, and instead turned his focus to the realist novels that would eventually make his name after leaving prison. Overall, Hikmet comes across as a kind of latter-day Turkish version of Gertrude Stein: a charismatic artistic sage, speaking in brilliant declarative sentences, dispensing wisdom on all subjects.

There’s a gentle, unfussy simplicity to this book, which is made up of chapters that are short and epigrammatic snapshots of life in jail. Kemal uses his novelistic narrative instincts to describe things, framing Hikmet’s much-anticipated arrival with a dramatic delay and presenting the dialogue in the best classical realist tradition. The central memoir is complemented nicely in this volume by a useful, contextualizing introduction by translator Bengisu Rona, along with extracts from Kemal’s prison notes and a few letters sent by Hikmet after Kemal was released in 1943.

After three years sharing a cell, this separation was hard on Hikmet, who would increasingly come to complain about his “intellectual isolation.” As a writer, Kemal isn’t really fit to polish his hero’s boots, but this is a charming and illuminating memoir of their time together, exemplifying the qualities of honesty and directness that Hikmet himself valued so highly.

Notable recent release

‘Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East’ by Scott Anderson

(Random House, $18, 592 pages)