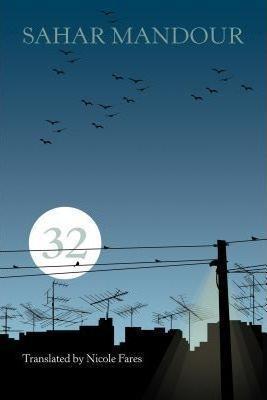

'32' by Sahar Mandour

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

I’m writing a story with a lot of events. Events that overlap and follow each other, without a chronological order, some that I remember from the past and others that go back and forth between imagination and reality. A lot of events that didn’t connect or lead anywhere, but do describe our reality. Our reality as it is.

Her struggle to finish this book, describing the lives of people who we ourselves have been reading about, give Lebanese novelist Sahar Mandour’s “32” a touch of postmodern flair. Mandour’s third novel, the first to be translated into English, presents an enjoyable slice of life in the Lebanese capital.

The story follows the eventful life of the 32-year-old narrator and her three friends Zumurrud, Zeezee and Shwikar. The book is without chapters and it is all presented in a kind of stream-of-consciousness first person narrative. Much of Mandour’s other work has bravely focused on sensitive LGBT issues in contemporary Lebanon but “32” generally steers clear. On the whole it flows well and is often wryly funny.

The freewheeling, slightly formless nature of the novel means it occasionally feels like Mandour is simply trying to fit various bugbears into her narrative. But its sharp dig at a European “amateur photographer” - ogling at the scene after a car bomb goes off “performing his duty … determined to enlighten people as to our plight” – is well-aimed.

Rather than that naive photographer’s deliberate, outsider’s eye, “32” gives us a more natural, authentic portrait of contemporary Beirut. The unfamiliar and the absurd are never far away. While Mandour is perhaps too keen to stress the ordinariness of life for upper-middle class Beirutis against a chaotic social backdrop, it largely feels authentic.

Many foreigners tend to read Arabic literature in translation looking for social clues to illuminate a broader political situation, but Mandour is keen to avoid forced artificiality. Despite Lebanon’s overweening sectarian political structure, there is refreshingly little talk of that in “32.” Overall, it is a worthwhile and original read.

Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here.