How not to measure corruption

As an economist, I cannot help but wonder if there is any way to red-flag corruption before it hits the prosecutors’ radars. The whistleblower who exposed Fatih Municipality gathered plenty of evidence, which he duly turned over to the district attorney, but what I have in mind is a methodology that would flash early warning signs for corruption at the country level, without hoping for brave souls like him.

It is not easy to identify and measure corruption, but defining it is even more challenging. As United Nations Development Program’s “A User’s Guide to Measuring Corruption” notes, “the term has been applied to such a wide variety of beliefs and practices that pinning down the concept is difficult.”

There are two broad types of corruption. UNDP defines petty corruption as street-level, everyday corruption, which “occurs when citizens interact with low- to mid-level public officials in places like hospitals, schools, police departments and other bureaucratic agencies. The scale of monetary transaction involved is small and primarily impacts individuals (and disproportionably the poor).”

The investigations in Turkey are about grand (or political) corruption, which involves large amounts of money. As the last two weeks have shown, the UNDP is right to emphasize “it negatively impacts the country as a whole, along with the legitimacy of the national government and national elites.”

There are also two broad types of corruption indicators. Input-based indicators, also called de jure indicators, measure the existence and quality of anti-corruption rules and regulations. Output-based indicators, on the other hand, look at the actual impact of corruption. Although they are also called de facto indicators, they are not based on firm facts because measuring output is tricky. For example, more corruption cases brought to trial could mean a higher incidence of corruption, more confidence in the courts, or as in the case of Turkey, “motivated” prosecutors.

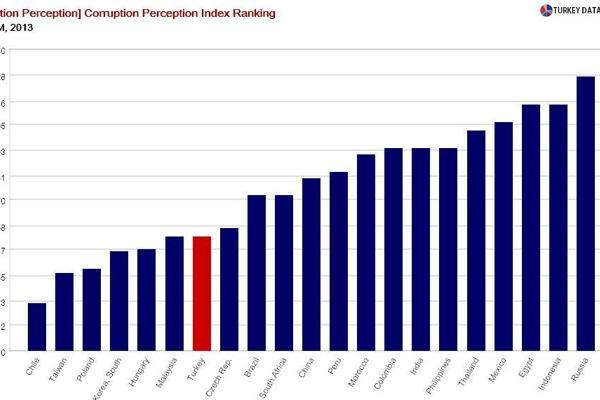

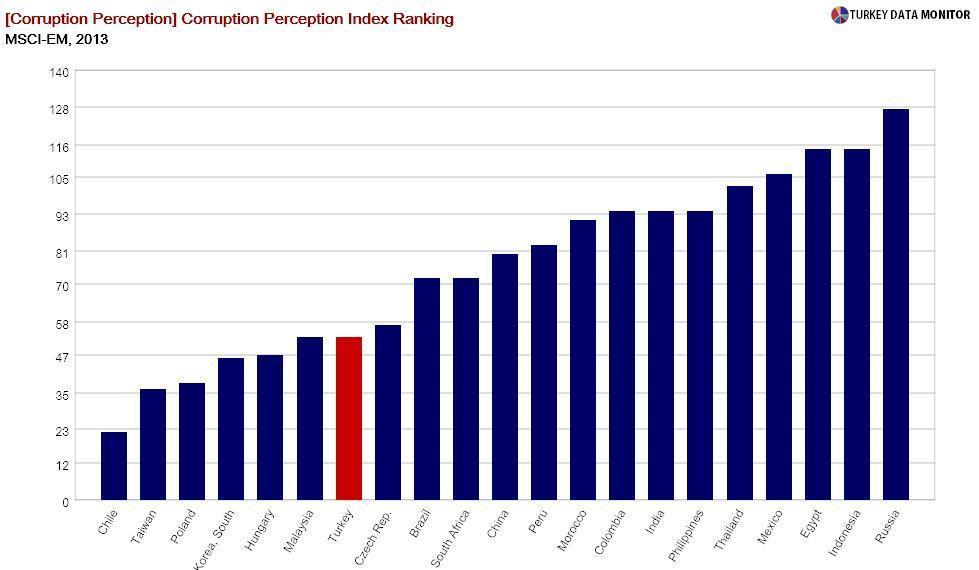

Researchers have turned to surveys in the absence of hard data. Some of these look at ordinary citizens’ perceptions or experiences of corruption, while others ask companies if they (or other firms in their sector) have to resort to bribes. Corruption indices that can be used to compare countries or track one through time are produced from such surveys. The most well-known of these is Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), which draws on 13 different surveys and assessments from 12 different institutions.

Turkey’s CPI rank improved from 77th in 2003 to 53rd in 2013, which would make Erdoğan pretty effective in fighting corruption! I’ll continue on Monday, if I don’t choke myself to death laughing first.