Dazed and Confused about the Current Account

The panel discussion “The Relationship Between Industrial Policy and the Current Account Deficit”, organized last Wednesday by the Turkish Industry & Business Association and Competitiveness Forum, illustrated just how much we are confused about both topics.

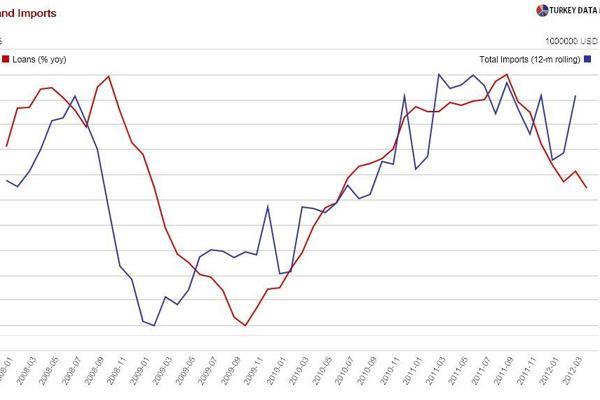

For starters, the subject matter might have been too ambitious. As Kamil Yılmaz of Koç University, one of the seven panelists, noted, industrial policy will not be sufficient to lower the current account deficit by itself, as it addresses just one cause - that we have to import a significant amount of intermediate inputs. But we also have a current account deficit because we borrowed to consume and therefore import. That’s why the Central Bank was trying to curb credit growth last year. And of course we have a current account deficit because we don’t save much.

As Murat Üçer of Turkey Data Monitor, another panelist, summarized, having a current account deficit simply means that we are spending more than we are producing. It is in fact normal for an energy importer with a young population to run current account deficits. But what would be the sustainable deficit for Turkey? Recent studies point to a figure in the range of 3-5 percent of GDP, much lower than the current level of 10 percent.

We also continue to treat the deficit as a structural issue, but part of it is really the result of deliberate policy choices. The Central Bank’s unorthodox policy mix did not manage to curb demand last year, and procyclical fiscal policy did not help, either. The economy grew 9.2 and 8.5 percent in 2010 and 2011, during which time 3 million jobs were created, so no one - least of all the government - would complain about this performance. According to economists, there is no free lunch. Current account deficit and inflation were the consequences of this surge in demand.

The latter might have even played a role in the so-called structural deficit. We argue that Turkey needs to be competitive, but we could have improved competitiveness just by bringing inflation under control. Movements in the real exchange rate, a simple measure of competitiveness, are equal to changes in the nominal exchange rate plus inflation differentials between the rest of the world and your country. With inflation constantly 5-6 percentage points above peers, Turkish goods have been becoming more expensive even without a nominal exchange rate appreciation.

Even for tackling the structural deficit, I agree with Üçer that there are easier fixes than a convoluted incentive scheme that tries to lower the deficit by identifying sectors highly dependent on intermediate input imports. For example, a seminar early in the month, organized by the Economic Research Forum, had several suggestions for a more effective tax system.

At an even more basic level, as panelist Ercan Tezer, General Secretary of Automotive Manufacturers Association, observed, the government’s efforts at lowering the current account deficit seem to be more about curbing imports than increasing exports, even though government officials emphasize that their policies are not a form of import substitution.

And I haven’t even started with industrial policy.