Gold as a decorative art in the Muslim Near East

Niki Gamm ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

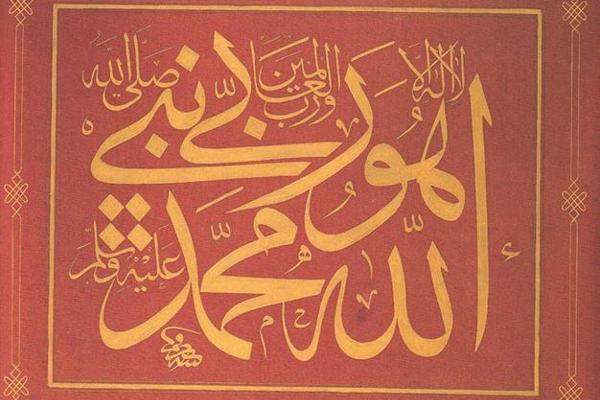

Berat and tugra of Sultan Murat III is iseen in the photo (R). Gold had a special place in the decorative arts, especially in calligraphy, one of the finest art forms in Islam.

Gold has a long history of decorative use in the Middle East starting with Egypt and continuing through Sumer, Babylon, Greece and Rome. In Islam, hoarding gold and silver is denounced in the Qur’an [Chap. 7, V. 34 and 35] and will result in punishment in the afterlife; accumulating it to use in God’s way was not and Islamic traditions [hadith] reinforced this. In spite of this, the prohibition seems never to have stopped the use of these two precious metals. It was impossible to totally ban the conspicuous use of the two luxury metals although not many examples from prior to the 12th century have survived. Many items would have been carried off as plunder or destroyed in the pillaging of cities and towns during the interminable wars and invasions that wracked the Near East. Gold and silver would also have been melted down to produce coinage.Calligraphy

Gold was not just used in jewelry; it had a special place in the decorative arts, especially in calligraphy, one of the finest art forms in Islam. The portrayal of human beings was acceptable only in two forms – miniature paintings and shadow play figures - and this discouraged the development of realism in art as distinct from how the human figure was portrayed in the Far East and Europe. The Qur’an as the word of God could not be translated into other languages so Arabic prevailed as the language of the educated elite throughout the Muslim world. It also came to be used in other ways such as dedication panels on buildings, tomb stones, eulogies and the like. Only Persian was able to rival Arabic as a language, except in religious contexts, but still it adapted the Arabic alphabet to its own needs and later the Turks did likewise.

It should not be surprising that, over the course of centuries, Arabic would change in the Muslim world under the impact of local influences. The Qur’an, traditions, legal books, etc. were memorized; being able to recite and repeat formed the basis of how one received a diploma. But memory wasn’t relied on in Muslim countries the way it was, in particular, in northern Europe in the Middle Ages where oral history was so important for preserving the memory of events. Books were copied and the better the calligraphy, the more they were valued. If you liked or needed a certain book, you arranged for it to be copied.

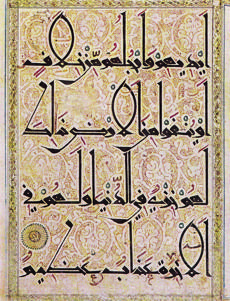

Calligraphers were among the best artists of the Islamic world. Not only did different scripts develop over time, but some calligraphers invented their own scripts. The first script in general use during the first four centuries of Islam was called kufic after a city named Kufa. It became more decorative over time and it was joined by the round cursive naskh calligraphic form around the 12th century. Mastering a script was one way of earning money, either by copying manuscripts or writing petitions. Another way was to become an important person’s secretary or work in one of the imperial government offices.

The Arabic alphabet doesn’t have capital letters so one never finds the first letter of a work emphasized the way medieval manuscripts in Western Europe were. While the calligrapher was responsible for the text in the manuscript or book, a separate person would illuminate it. It would be the illuminator’s job to do the title pages, chapter headings and border medallions. The Qur’an offered the greatest scope for his talents. Often books would be ordered illuminated so that they might be presented as gifts to important people. Persian illuminators on the other hand devoted most of their time to miniature painting and later passed this interest on to the Ottomans. In fact whenever an Ottoman sultan conquered an important Iranian city, he would send the artisans there to Istanbul and so miniature painting became important. Some of the Ottoman sultans for example commissioned histories and volumes of works regarding the House of Osman, that is, the imperial dynasty, or events in their own reigns such as circumcision festivities. Nor should one forget the elaborate tugra or monogram that had to be drawn on edicts before they became legal.

Works at this high a level incorporated the best materials and two of the most important and expensive materials were gold and lapis lazuli. The latter was usually obtained from the Afghanistan region and so was rare, while gold is found throughout the Middle East. The famous story of Jason and the Golden Fleece reveals that gold was “panned” in the eastern Black Sea region from very early on.

Panned is the wrong word of course for placing a sheep skin in a river and catching gold flakes on their way downstream in the wool of the fleece. The fleeces would then be dried and the flakes shaken or combed out.

A gold nugget of 5 mm in diameter can be expanded through hammering into a gold leaf of about 0.5 square meter and it would have had to have been beaten several thousand times to obtain the finest gold dust.

According to Uğur Derman in Letters in Gold, “Gold ink was made by pulverizing high-karat gold leaf into a fine powder in a thick solution of gum Arabic or honey in a porcelain dish… the substance was rinsed in water to remove the gum or honey, and the gold strained into another dish, leaving the finest gold dust. Gelatin dissolved in water was added. The gold ink was applied to the nib of the pen with a special brush as needed.”

In discussing calligraphic decoration, Derman says, “The word tezhip (or tezhib) refers primarily to the application of pure gold with a special brush, but it also encompasses the use of a varied palette of colors accompany the gold. Both yellow (23- to 24-karat) gold and green (18-karat) gold are used, with different burnishing techniques employed to achieve different effects, such as brilliant or matte gold.

Another style of ornamentation, halkari (dissolved-gold work), uses no color except for the color of the background paper. In this technique, the motifs are painted in a wash of gold ink, giving a subtle shaded effect, and outlined in full-strength gold ink.”

Gold was also used on the leather bindings for books, a practice that possibly came from Central Asia. The designs indicate the times and places where they were made but frequently consisted of sunbursts and floral arrangements.

Much rarer are instances when gold flakes were mixed with the dyes used to produce ebru or paper marbling that was to be found in books as decoration or the background for calligraphy. Today however the price of gold has risen to such heights, it’s practically beyond what an artist can pay, assuming of course he or she wanted to return to the practices of old.