Crime and punishment: The Ottoman legal system

Niki Gamm

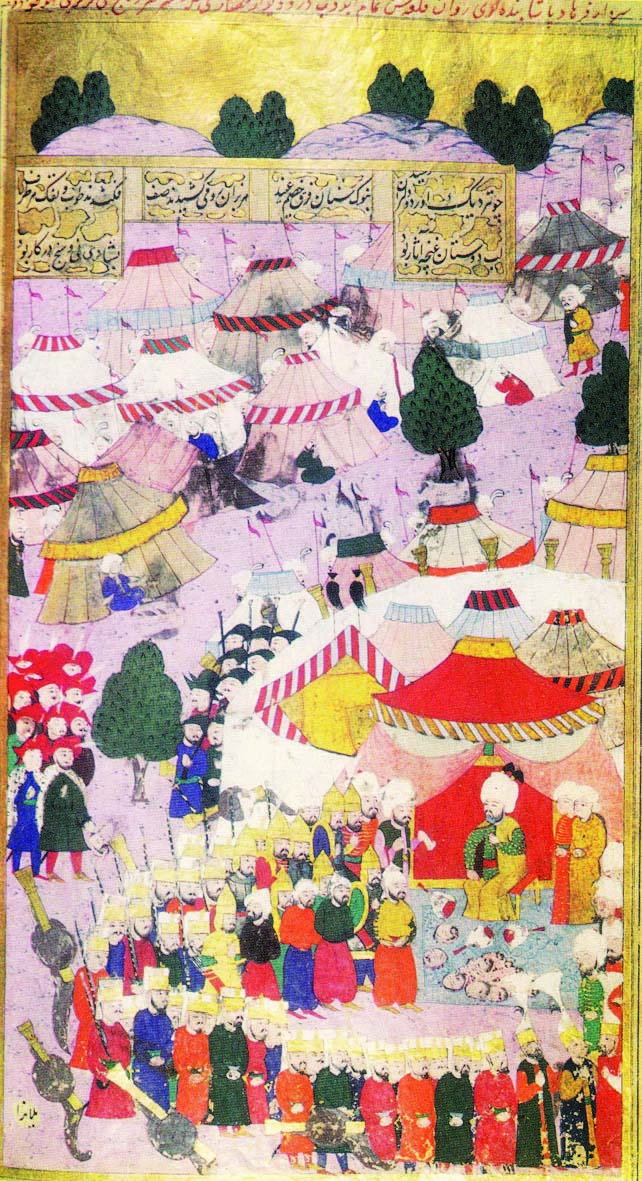

Çelebi Sultan Mehmet I on route to the Wallachian campaign, punishing thieves who have stolen honey from hives at Rusçuk on the Danube.

The sharia (Islamic law) “is the totality of God’s commands that regulate the life of every Muslim in all its aspects,” (Joseph Schacht, “The Legacy of Islam”). However, after Islam expanded out of the Arabian Peninsula, it was confronted by cultures that were different and situations that were not covered by these commands. The sharia, which never became associated with political power, over time achieved a special position in that it was referred to and used as the standard against which laws concerning practical situations were measured.By the time the Ottomans had begun their rise to power, a number of Muslim governments in the Middle East had already developed their own legal systems alongside the sharia. The Ottomans would, in any case, have developed a legal system to deal with subjects outside of the sharia. As the empire grew, this legal system referred to as örf law, was based on two sources - laws promulgated through decrees issued by the highest power of the state, the sultan, and customary usage or norms. The terms örf and sharia were used together for the first time during the reign of Fatih Sultan Mehmed II (1451-1581) by the historian, Tursun Bey.

The Ottomans preferred to leave the legal system (örf law) and norms already in place in the areas they conquered and only gradually replaced them with decrees (kanun) through the use of the court system. While kanun went into effect only after the sultan approved them, they would normally be prepared beforehand by the members of the Divan, or Imperial Council, the paşas and nişancıs, the latter being responsible for affixing the sultan’s signature (tuğra) to the decree. It should be pointed out, though, that these decrees weren’t applied uniformly throughout the Empire. Mehmed Akif Aydın, in “The Ottoman Legal System,” points out that these örf laws were only enforceable during the reign of the sultan who approved them. They had to be re-approved by the following sultan.

“The most important difference between the substantive criminal law of the kanun and the sharia is the imposition of a fine [with or without strokes] upon criminals liable to the fixed penalties [hudud], sometimes more severe, of the sharia. Formally, of course, the kanun cannot commute these penalties into lighter punishment. Consequently, it imposes fines for fornication only if no capital punishment is inflicted; for homicide or for the knocking out of en eye or tooth only if no retaliation is, or is to be, carried out; and for certain cases of theft only if the thief’s hand is not to be cut off. In some statutes, however, these conditions are not explicitly stated, and it is taken for granted that fines are the only penalty applicable to the crimes mentioned,” (Uriel Heyd, “Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law”).

Heyd also points out that the penal codes were intended not just to protect society against criminals, but also to protect “the common people against oppressive officials and fief-holders.” He cites a 15th century kanunname, issued on behalf of the Christians of Cephalonia, an Ionian island off the west coast of Greece, who had complained against tax-farmers and others. He also quotes Celalzade Mustafa Çelebi in the 16th century as rather colorfully saying, “The gates of oppression and aggression were fastened with the nails of the kanuns.”

In terms of punishment, there were only two major distinctions. One was for serious crimes which warranted capital punishment, banishment or some kind of corporal chastisement (amputation of a hand or foot) and all other crimes, the punishment for which might include exposure to the public, imprisonment, service on Ottoman ships, etc.

Capital punishment for homicide, arson, stealing a horse, a prisoner of war or a slave and repeated thefts was carried out by hanging, even though the word salb means crucifying, strangling, impalement, decapitation, etc. In some instances blood-money and a fine might be substituted instead. Heyd adds to the list subject to capital punishment “offenses against public order and security, the possession of fire-arms by civilians [in Egypt], serious violations of market regulations, counterfeiting, acts of disobedience against the Sultan and the spreading of calumnies about him, the illegal sale of grain and export of arms to foreign [Christian] countries, etc.” in addition to heresy and apostasy. As for the punishment for lesser crimes, it has been noted that in times of financial distress, fines were imposed on more people at higher rates and when the Ottoman navy needed to rebuild its fleet, such as after the disastrous defeat at Lepanto in 1571, more prisoners were sent to serve as rowers in the fleet.

The sultan, grand vizier and other officials of vizier rank had the right to execute any of their officers or officials unless they were members of the ulema, or religious scholars. The latter and other subjects had the right to a trial by a judge. The property of someone put to death was not necessarily confiscated for the public treasury, but would be handed down to that person’s heirs. However, if the executed individual were a member of the imperial household, his property would automatically revert to the sultan, unless the sultan had mercy on that person’s family. The execution of a criminal was to be carried out in the place where the criminal act took place, although in latter centuries, the area in front of the Bab-i hümayun (the first gate of Topkapı Palace) or by the Alay Köşkü across from the Bab-i Ali. No executions were carried out during the month of Ramadan.